The recklessness of the ‘Prudent King’ that shook the world’s largest empire

A new book reveals the factors that led to the defeat of the Spanish Crown under Philip II in a conflict characterized by heroic feats and terrifying excesses

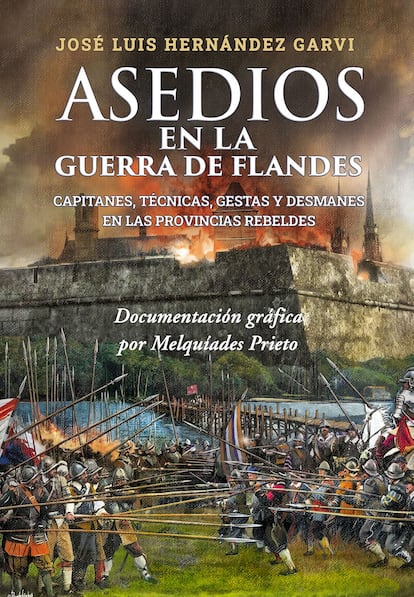

According to many historians, the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648) was King Philip II’s greatest political and military mistake. His stubborn refusal to acknowledge that it was completely impossible to sustain land warfare hundreds of miles away from Spain – with an enemy, France, strategically located between the Iberian Peninsula and the Netherlands and England blocking the English Channel – caused a colossal economic, social, military and reputational crisis for the Spanish Crown. Unlike his father, Charles I, the so-called Prudent King squandered both fortunes and lives in an exercise even his best and most faithful captains did not believe Spain could succeed in; they accepted it, though, knowing full well that they were headed straight to the hecatombs. The monarch’s dogged determination to impose Catholicism by blood and fire on the 17 rebel provinces of the Spanish Netherlands left scenes of terror and inhumanity etched in posterity, as well as instances of military heroism that are hard to believe. The king’s irrational drive for victory at any cost forced the Spanish formations, known as Tercios, to modify their existing war tactics radically and rapidly. José Luis Hernández Garvi’s enlightening new book Asedios en la Guerra de Flandes (or, Sieges of the Eighty Years’ War) analyzes the conflict that exhausted the Spanish empire and gave rise to the Black Legend: the perception that Spanish colonialism was uniquely cruel and intolerant.

Hernández Garvi notes that Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (who ruled Spain as Charles I) maintained his realm’s territorial integrity under a centralized government. For 24 years, his sister Mariana of Austria served as ruler of the Hapsburg Empire with an effective containment policy that gave the provinces a “period of stability and prosperity that they had never known before.” The emperor respected their most representative institutions and maintained a low tax policy. But the advent of Philip II’s rule degenerated into a political clash that reached the level of open warfare with “episodes of extreme violence.”

The monarch’s intransigence and centralist absolutism angered those who ended up being his most fractious subjects

When the spark of Protestantism ignited in Flanders (now a Dutch-speaking region of Belgium), the author notes, important reformist nuclei arose in the cities, to which the local Inquisition Holy Offices responded forcefully. These excesses “planted the seed of rebellion… The monarch’s intransigence and centralist absolutism angered those who ended up being his most fractious subjects.” The initial discontent led the local nobles, who had been loyal to the king until that time, to decide that it was time “to assume power.” Prince Maurice of Orange, William of Nassau, and the Counts of Egmont and Horn led the revolts in the Spanish Netherlands. Nevertheless, there was a final attempt to avoid the disaster, the so-called Compromise of Breda, in which Philip II’s legitimacy would not be questioned in return for the Spanish Crown granting “freedom of religion and vetoing the Inquisition.” The monarch responded categorically: “No concessions of any type.” If he gave in, that might be interpreted as a sign of weakness. The die was cast; the war began.

From the outset, the Spanish Crown’s military experts were aware that the tactics used in other armed conflicts were not applicable in this situation, which was completely different and involved dams, canals, rivers, heavy rainfall, muddy terrain, and fortified cities (cases of incompetence were rare, although they did exist as well). They had to forget the great past battles that had covered Spain in glory and honor and adapt to a different kind of warfare: the siege.

The Spanish Crown’s military experts were aware that the tactics used in other armed conflicts were not applicable in this situation, which was completely different

On the one hand, the Spanish troops erected strongholds along the Rhine and Meuse rivers to block the rebels’ supply lines; on the other, the Dutch hurried to fortify their main urban centers against future attacks. The empire’s artillerymen then generalized the widespread use of the mortar (a parabolic gun that overcame defenses), terrorizing the besieged population. The rebels responded by copying the design of the revolutionary Italian fortifications, which included sloping and massive parapets with polygonal and star shapes and corners and bastions that protruded to prevent blind angles. In turn, the Spaniards developed the technique of using subterranean mines to reach the walls and blow them up undetected. Thus, the Netherlands experienced fierce battles that occurred underground and in total darkness.

The attacking army’s arrival at the gates of a city marked the beginning of a siege. Camps were set up at a distance to house troops and to maintain their headquarters, circumvallation lines (fortifications) were constructed around the besieged city and artillery placed. The first bombardments served to gauge how far the besieged populations were willing to go, and their level of military response. If the defenders did not lower the flag, the attackers turned their attention to destroying the walls. Infantry then advanced through the open breach. “Amid the chaos, the soldiers – dazed by fear and the din of combat – made their way as best they could through the point-blank shots that decimated their ranks; in those critical moments, unintelligible orders, insults, blasphemies and litanies of prayers combined in an indescribable cacophony of voices and sounds that emulated hell,” the author writes. “The smoke from black powder and the dust produced by landslides made it difficult to see and created a suffocating atmosphere under the gloomy hum of bullets and shrapnel, taking [many] lives. The screams of the wounded and mutilated overwhelmed the faint-hearted, who were pushed or trampled by those behind them.”

Both sides experienced indescribable atrocities following the sieges. On June 27, 1572, the city of Gorkum, Netherlands, which was pro-Spain, surrendered. Despite his promises to respect the lives of the city’s inhabitants, Dutch Commander Willem van der Merck sacked it. He ordered the arrest of 19 Catholics, tortured them, paraded them in a procession, exhibited them naked and sadistically subjected them to torments as they sang the Te Deum.

The screams of the wounded and mutilated overwhelmed the faint-hearted, who were pushed or trampled by those behind them.”

On October 2, 1572, the Duke of Alba’s Spanish troops appeared in the city of Mechelen [in today’s Belgium]. Panic ensued and the defending soldiers fled. The square opened its gates, but the duke ignored the terrified inhabitants’ pleas for mercy and authorized the sacking of the city. The Spanish Tercios – which made up only 10% of the duke’s troops – started the rampage, while Walloon and German soldiers continued it for the next two days. “The scenes of arson, murder and rape, which illustrated this barbarous custom again, did a disservice to the already sad reputation of Spain’s armies,” writes Hernández Garvi.

Numerous sieges (at Maastricht, Antwerp, Middleburg, Groningen, Breda) took place during this brutal war, and there were an equal number of commanders killed or maimed who were heroic in their military actions. Spanish troops were true experts in organizing incredible night operations, which today we would call commando units, to cause confusion among enemy troops.

“The [Spanish Crown’s] decline was sealed at Rocroi [in France],” writes Hernández Garvi, “and the feat accomplished by the Genoese captain general [Ambrogio Spinola’s victory at Breda in favor of the Spanish monarchy] soon evaporated, like a mirage that deceived [the hopes] to which the [Hapsburg] dynasty in decline clung. Contemplating Velázquez’s marvelous painting, exhibited in Spain’s Prado Museum, with its artistic liberties and undeniable historical value, takes us back in time, closer to an era in which heroes and villains, cowards and the brave, great lords and loyal vassals, fought for glory, sharing sacrifices in a struggle that deserves to be remembered.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.