The bassist who designed a Beatles album cover for only £40

Bassist and designer Klaus Voormann – who once shared a flat with Ringo Starr and George Harrison – convinced The Beatles to break with the colorful psychedelic trends of the 1960s and release an album with a black-and-white cover

The life of German designer and bassist Klaus Voormann changed on the night of October 16, 1960, when he ended up in a seedy bar after an argument with his girlfriend.

The Kaiserkeller – or “the emperor’s basement” – in Hamburg, Germany also doubled as a music club. As Voormann drank his beer alone, he listened to a group of young men rocking out on stage.

“I was fascinated by the sounds that those guys were capable of creating,” he recalls, 62 years later, in a telephone conversation with EL PAÍS. Those guys – John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Stuart Sutcliffe and Pete Best – were the original members of The Beatles.

Voormann and his then-girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr became friends with The Beatles. They fed them, took them to movies and art galleries, snapped photos of them and helped them invent their legendary hairstyles. Eventually, Kirchherr fell in love with Sutcliffe, the group’s bass player, who subsequently left the band.

After honing their skills, The Beatles returned to England, where their popularity exploded.

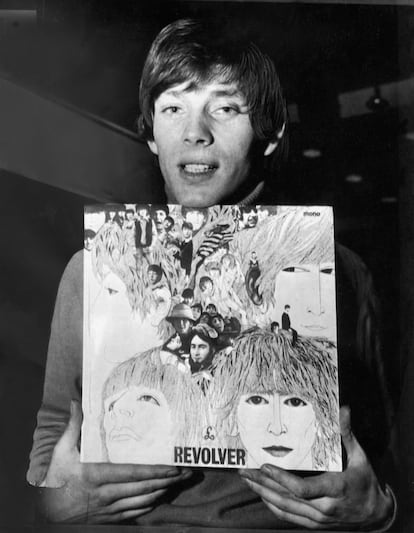

By 1966, however, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Ringo Starr – who joined the band as a drummer in 1962 – had grown weary of touring. They wanted to experiment with new tunes… and new drugs. They wanted to make real art, while still being able to sell enough records to keep up their lavish lifestyles. Revolver – their seventh studio album, completed in 1966 – seemed to do the trick. But once the songs were all recorded, they needed a cover.

“I was home early in the morning,” says Voormann, who had moved to London a couple of years earlier from his native Hamburg. “I had been out all night, so I was taking a bath, relaxing. And the phone rang.”

He remembers being annoyed that he had to dry off to answer the call. “Hey, this is John,” the voice in the earpiece bellowed. “Which John?” Voormann grumpily replied.

“Lennon was quite upset that I didn’t recognize his voice,” he laughs. After he calmed down, the iconic guitarist and singer asked the German designer if he had any ideas for an album cover. Shortly after that, Voormann went to EMI Studios (now renamed Abbey Road Studios) to listen to the whole record.

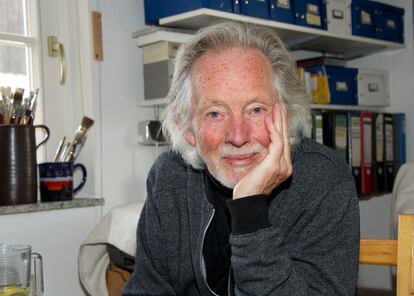

“It was fantastic. Indescribable,” recalls Voormann, now 82. “It was a big step into the future. The songs were strong. And they recorded them in a simple way, without too much orchestration or choirs. They were very direct, very personal. They captivated me.”

The friendship between Voormann and The Beatles had been forged years before they asked him to help them out with the album design.

“In Hamburg they were very lonely, nobody took care of them. They were just kids: George [Harrison] was barely 17-years-old.” Harrison would eventually be deported from Germany for working as a minor.

“I knew them before they were famous… with all the people they met later on in life, they always doubted whether those friendships were sincere.”

So, when Voormann decided to move to London, Harrison and Starr made room for him in their apartment, taking advantage of the fact that McCartney and Lennon had moved in with their girlfriends.

In London, Voormann began to carve out a career as a designer. But after he heard the songs in Revolver, he spent three weeks holed up in the kitchen of his tiny apartment in North London, brainstorming on a sketchpad.

Despite it being the psychedelic era – in which wild colors were trendy – Voormann proposed that the album design be in black and white.

“I proposed it to them and they responded enthusiastically,” he says. “These guys weren’t stupid. Quite the contrary. At that time, everything was in color, so they thought it was a good idea to stand out.”

Working with a black ink pen, he drew a cascade of images of the band members, while also using photographs to make a sort of collage.

“It was a very laborious process: drawing, cutting, scanning... I wish I had been able to use today’s technology!”

“When I get a commercial assignment, I sit down and write the ideas that come to me,” he explains. “It was clear to me that I had to think about the fans – accustomed to songs like Love Me Do or I Wanna Hold Your Hand – and prepare them for the new album’s loops, with guitar solos played backwards. I had to build a bridge.”

The resulting cover was not only a bridge to a new style of music – it was considered one of the best drawn ones in history.

For his craftsmanship, Voormann received the princely sum of £40 ($47).

“The record company told me that they couldn’t pay more for a cover,” he laughs. “Anyway, at that point, I would have done it for free. I was so proud that I didn’t think too much about what I was going to charge – I didn’t want to push.” The commission, at least, catapulted him to international fame. He joined Manfred Mann, a band that played between 1966 and 1969 and enjoyed considerable success.

In 1967, Voormann’s design won the Grammy Award for Best Cover. In the early 1970s, he moved to Los Angeles and worked as a bass player, taking part in some of the greatest albums of the decade, including Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. He was the lead bassist at the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh, organized by Harrison and Ravi Shankar in Madison Square Garden to raise awareness and money for refugees fleeing East Pakistan.

Voormann also played bass in almost all of John Lennon’s solo albums and in three of Ringo Starr’s albums. In 1995, he designed the covers of all three volumes of The Beatles Anthology.

“I remember a lot from that time, of course. Playing with John, with George... But that’s the past. I really enjoyed it, but it’s over.”

Music has since lost its meaning for Voormann. “When I came back to Germany [in 1979] I started a career as a producer. But I didn’t like it. And I didn’t want anything to do with the bass, either. I was so spoiled to have been able to play with so many fantastic musicians around that world that, in my country, I lost interest.”

The years have also taken a toll on his body. “My hands don’t work like they used to,” he admits. “I can’t play guitar, I can’t play piano, I can’t play bass!”

When asked if Revolver is his favorite Beatles album, he hesitates. “Oh… I always forget names. What’s the one just before Revolver? What was it called?” He moans, trying to remember. “Ah! Yes! Rubber Soul! Revolver and Rubber Soul. Yes, those are both my favorites.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.