Pattie Boyd is sick of being called a muse: ‘What have I done to inspire George Harrison?’

The ex-model Pattie Boyd, who documented the London of the 1960s and became the subject of songs by The Beatles and Eric Clapton, reflects in the book ‘My Life in Pictures’

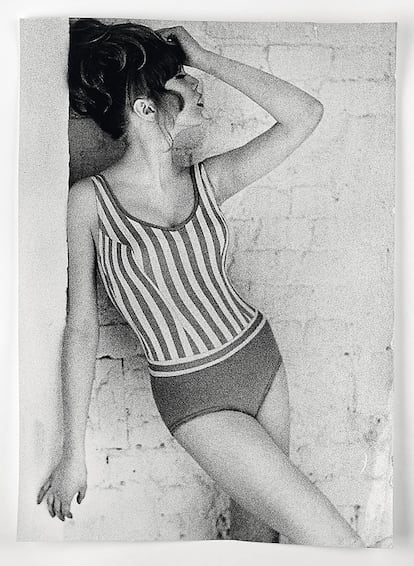

It was London in the sixties, the time of Mary Quant miniskirts and youthful freedom on Carnaby Street, King’s Road and Kensington. Michael Caine sat behind the wheel of a 600, and David Hemmings wore white pants and wielded a camera. It was a time of protests, drugs and ideas. And, above all, it was the time of Pattie Boyd.

The model, photographer and actress inspired almost a dozen songs from rock’s most mythologized stars. She was a key figure in an increasingly complex society, an icon who connected John Lennon with the wealthiest pockets of the time. She was ahead of the changes that were coming. Elizabeth II was reigning over Britain, but Pattie Boyd ruled over London.

The story of that life appears in Pattie Boyd: My Life in Pictures (Reel Art Press), a biography in images of the 78-year-old who was born 200 kilometers from London. By 1962, she had moved to the capital and begun working in the legendary beauty salon of Elizabeth Arden as a shampoo girl. That didn’t last long. “I was there just because I needed work. A woman came one day and asked me if I’d thought of being a model, and said that if I was interested, I should go see her the following week,” she recalls today from her apartment in Kensington, where she received ICON.

That woman turned out to have contacts in the magazine Honey, at the forefront of modernity. Shortly thereafter, Boyd found an agent. “Then came the most complicated part: persuading photographers to take photos of me. So I worked with a lot of young people. They needed experience and I needed photos, so that was the process for a long time,” Boyd recalls. Among those young photographers were David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy. “I also admit that I couldn’t really believe it, and every time that I got it, I thought, I’m so lucky. Then another session would happen and I would think the same thing: this one hasn’t realized either.”

A few years later, Boyd, all bangs and big eyes, had become the most famous face of Swinging London. Twiggy, the legendary model of the era, who is also a close friend of Boyd, declared her to be her essential influence. Mary Quant said that every modern woman aspired to look more like Pattie Boyd than Marlene Dietrich. Meanwhile, Boyd rubbed shoulders with the most legendary actors, poets and musicians of the era. “I’ll tell you something: it’s been so long since that happened that, when I think about it, I always have the sensation that I’m watching someone else’s life. I also don’t remember most of it: I remember fun parts and I still have the best memories, but the rest is very far away,” she jokes.

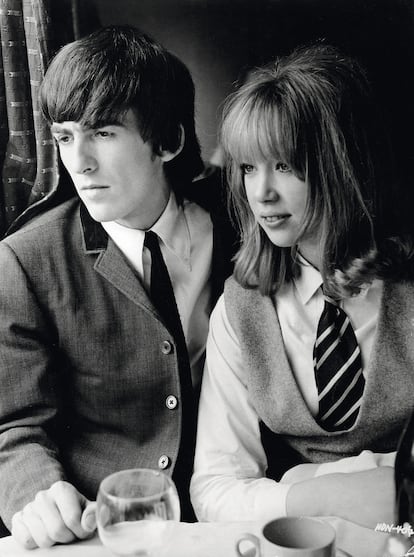

She does remember one pivotal moment: “A guy came over once and saw my book, and I think he liked it because he hired me. I thought it was another TV commercial [Boyd had just shot a spot for Smith’s chips], but that night my agent told me I had been booked in a film with the Beatles. I told him that it couldn’t be, how was I going to appear in a Beatles movie? But it turned out that it was true. [The Smith’s ad had been directed by Richard Lester, the Liverpool film collaborator and director of their first film, A Hard Day’s Night]. I was just going to say one sentence and wear a schoolgirl uniform, which seemed ridiculous, but okay. Then everything else happened, so I’m not going to complain.”

By “everything else,” she means that she fell in love with George Harrison. They ended up marrying. She was, in fact, the one who introduced Harrison to the realms of Indian spirituality. She became a fixture on the band’s travels, eventually changing the sound of the biggest band on the planet forever. Revolver (1966) included the sounds of sitars. Then the Rolling Stones borrowed the idea for Paint It Black, and by 1968, the Beatles were making group trips to India to learn to meditate. “I don’t miss those times,” she says with septuagenarian sarcasm. “If I could transport myself there right now, I would love it, of course, but I loved my life then the same way I love it now. It was living in a bubble, surrounded by famous people, where all doors were open to you. But even today I lead a wonderful life. Did the fame of the group affect me? They did not behave as if they were special. They were ordinary people. That made everything very easy,” she recalls.

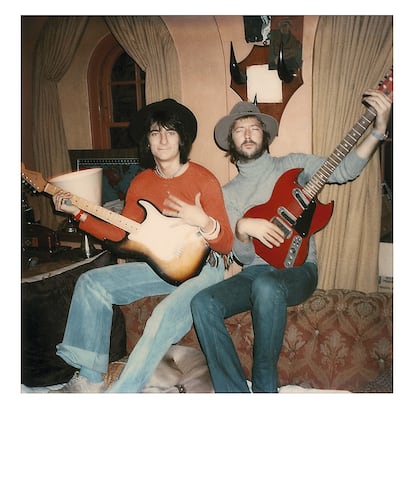

Harrison’s divorce ultimately cemented Boyd’s legendary status. Shortly before the Beatles split, the guitarist had begun collaborating with his friend Eric Clapton. With the group disbanded, Harrison and Clapton spent time playing together with Boyd photographing them. Clapton fell in irrevocably in love with her, so much so that he dedicated a song to her, Layla. Today, that seven-minute ballad about a woman you can’t have is one of the most famous anthems in ‘70s rock.

Boyd ended up leaving Harrison for Clapton. That was the first of many songs dedicated to her. “I’m not a muse,” she says. “I mean, I understand what you’re referring to, but for me, and I say this with complete sincerity, everything is in the hands of the artist. It’s all in their head. They project that on whoever they want, but that’s the artist’s problem. Having said that, it makes me really happy to listen to them, but I’m not such a narcissist to believe that they’re talking about me. I don’t believe it. I still remember the first time that George told me he’d written something for me. I looked at him and I said, ‘Why did you write a song for me? Why do I deserve a song? What have I done to inspire it?’”

One point she recognized: Boyd is a reasonably successful photographer whose documentation of the era, primarily of the Beatles and Clapton, has been shown all over the world. She wasn’t just an icon of the era; she was also its historian. “I remember how free and happy I felt and the sensation to think that the world would never change. I noted that zeitgeist in the air. The creativity and excitement and the sensation that we were about to arrive at something new filled everything. The amount of painters and musicians who emerged, great artists, great photographers, the amount of cinemas…it was an incredible time,” she remembers.

And now? The times of Twitch, Twitter, TikTok? “Impossible. It wouldn’t have been possible at all. With social media it is really hard to do what you want to do, decide who you are, being connected to everything at every minute, without a break. It would have completely overwhelmed me,” she recognizes.

Now, with the release of the book, Patricia Anne Boyd once again finds herself before the cameras and the microphones. “This isn’t something that scares me. It’s not like I’m at home all day watching television, you know? I go to the theater, I still take photos and I have a very active social life, so it won’t be a big change.” Before saying goodbye, when asked to summarize the lessons from her adventurous life, Boyd pauses. “It’s essential to be faithful to yourself, not betray yourself, be honest and allow people to know you for who you really are. I don’t think there’s anything quite as important.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.