Feed them to the lions! How Ancient Rome demonstrated its brutality and power

The Roman rulers used gladiator games to entertain the public – but these battles also served as political theater

Rome was the first European civilization fascinated by wild and exotic animals. These creatures became symbols of power and weapons of war, used to inflict merciless punishments against criminals or dissidents. “To the lions” was the favorite phrase of Julius Caesar in the comic book series Asterix and Obelix, just to demonstrate how widespread the phenomenon was.

The ancient Romans were relentless in their quest for rare creatures. They even caused extinctions of several species in Northern Africa, depleting animal populations to bring great beasts to fight in their amphitheaters, or to use them for trading purposes. The American writer, Paul Bowles – who lived most of his life in Tangier and travelled heavily throughout the Sahara – wrote that “a great number of elephants that roamed the desert were captured and trained to become part of the Carthaginian Army… but it was the Romans who finally annihilated the species in order to obtain ivory for the European market.”

In her book, The Medici Giraffe and Other Tales of Exotic Animals and Power, art historian Marina Belozerskaya wrote that “the battles with exotic animals grew in size and splendor with each territorial conquest. They began as a way to entertain and control the populace and make them symbolically share in the glory of the state. But as the people became more and more addicted to these displays, politicians had to promote them to secure popular support. Ultimately, a ruler’s reputation ended up depending on the games he organized.”

The animals were utilized for the purposes of combat, as simple exhibitions (giraffes aroused the most astonishment) or for particularly cruel executions. Images of Christians being devoured by lions have become popular in movies, novels or paintings about ancient Rome… and they are quite accurate portrayals of reality.

Animals were annihilated on a truly formidable scale. Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard recount in their book The Colosseum that, in just a handful of games organized by Pompey the Great, 20 elephants, 400 leopards and 600 lions were killed. The Emperor Augustus estimated that, during his reign, some 35,000 animals died in spectacles. And these were not simple shows: mythological or historical scenes were often recreated.

“The logic of these shows was very clear,” Hopkins and Beard write. “It was a dramatization of the conquest of the world by Rome. It would be hard to contemplate the slaughter [during the reign of Augustus] of Nile crocodiles in the arena, without thinking that it reflected the fact that Egypt had just been subjugated by Rome.”

But all these festivals filled with cruelty and death raise a question to which there is only a partial answer: how were all these wild beasts – sometimes travelling from as far away as India – captured and handled? As can be seen in the movie Gladiator, Bengal tigers were present in the arena. Chronicles also reflect the presence of rhinos, both Asian and African, and even polar bears!

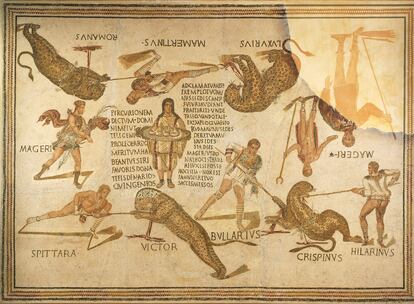

Spanish researcher María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, has published a comprehensive study on this subject: “Of all the artistic manifestations… the mosaics are perhaps the ones that offer us the most information about the animals’ capture phase,” she writes. The capture surely began with someone powerful deciding to commission a show – the hunters subsequently recruited were a combination of natives and legionnaires. “There is evidence that Roman troops were involved. It was probably part of a soldier’s duty or training.”

Trapping systems were surely used, either through cages with baits or holes in the ground, although, the author explains, “the system did not work well with elephants due to their herd character and cooperative instinct. An unexpected technique was used for the panthers: a puddle was filled with wine and, when drunk, the feline became tame – I don’t think any legionnaire would have been excited to be the person to check if the trick had worked.”

Regarding the form of transport to reach the metropolis, mosaics and paintings from the 3rd and 4th centuries indicate that the process was carried out by sea. There are countless images of elephants boarding ships via ramps, as well as cages on decks containing bears and lions.

All of the expensive and sophisticated systems used to capture and transport animals from the ends of the earth were created to do more than simply amuse the masses with sadistic spectacles. The notion of tearing the enemies of the Roman Empire into pieces – be it with the teeth of lions, tigers or bears – was, above all, a display of power. A message that nothing would stop Rome in its desire to dominate the world.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.