Dora Goldsmith, the Egyptologist who reconstructs the world’s oldest perfumes

This expert from the Free University of Berlin has spent a decade studying and emulating fragrances from pharaonic times

Aromas and scents were very prominent in the important occasions and daily lives of ancient Egyptians. Hieroglyphics engraved on temple walls and inscribed on papyrus scrolls testify to a long tradition of fragrances and perfumes. The most exquisite creations became an indispensable part of offerings to their gods and gained worldwide renown.

When Amun, the ancient Egyptian deity, appointed the famous female pharaoh Hatshepsut in 1478 BC, he commanded her to launch an expedition to the Land of Punt, an ancient kingdom southeast of Egypt. The expedition’s mission was to bring back myrrh trees so that heaven and earth would be awash in divine aroma. As part of his morning rituals, King Ptolemy X had himself anointed with the finest perfumes, and one of the oldest medical scrolls ever discovered describes the fragrances that filled the houses of noble Egyptians.

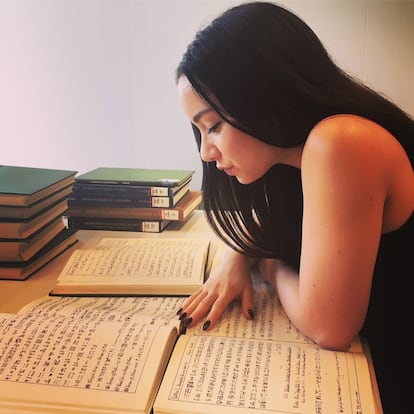

Dora Goldsmith, an Egyptologist at the Free University of Berlin (Freie Universität Berlin), is a leading expert on the fragrances of ancient Egypt. For the last 10 years, she has searched pharaonic texts for references to scents, and more recently has started recreating perfumes, fragrances, and other personal hygiene products used at the time by following the recipes she has discovered.

“I started doing these recreations because I wanted to understand the texts better. My research focuses on understanding the ancient Egyptians’ perspective on aromas – they wrote a lot about the smells and fragrances all around them. I wanted to experience that myself to better understand the texts and the Egyptians, so I could get closer to them and better understand their culture,” said Goldsmith.

What did the ancient Egyptians mean when they described a divine scent? What were the wonderful fragrances that emanated from the lush gardens portrayed in their love poems? Did they achieve their goal of smelling good in the afterlife? To answer these questions experientially, Goldsmith began collecting the aromatic ingredients that she had identified in her study of ancient inscriptions and texts. She eventually created a catalog of more than 200 aromas.

Edible fragrances

The next step was to recreate some of these fragrances, and she chose to start with kyphi, one of the most well-known perfumes of ancient Egypt. It’s also considered to be one of the first perfumes ever created. Goldsmith says that it was often burned like incense to perfume homes or a woman’s clothes and hair. Since it is edible, it was also made into a type of chewing gum. Kyphi is unique in that there was a specific variety only used in temples dedicated to the gods. It was more extravagant, had many ingredients, and was difficult to prepare. A simpler variety was made for mere mortals to use as a perfume, says Goldsmith.

Goldsmith begins the process of recreating an ancient Egyptian aroma by first translating the text with the recipe. Next is the botanical identification of the recipe’s ingredients, a difficult task that Goldsmith considers “part of the art” because there are no direct translations. She then collects the raw materials, trying to adhere closely to the ingredients used by the ancient Egyptians. Goldsmith examines the smell, consistency, and color of each ingredient, and then makes the recipe, step by step.

Goldsmith has recreated four perfumes from recipes inscribed in temples and created specifically for the gods, although they were sometimes used for mummifying wealthy humans for the afterlife. She says these types of perfumes take a long time to make and are usually expensive because of the rare ingredients and the time-consuming process. Goldsmith has also recreated a deodorant and a facial mask for skin care used in ancient Egypt. “These products are antibacterial and antiseptic, and are very good for the skin, so they would certainly work [today],” she said. Goldsmith has also produced some unique ointment cones that were worn on special occasions.

Goldsmith also recreates what are known as scent landscapes – the smells that were present in certain places and environments of ancient Egypt. Some of the scent landscapes she has recreated include a bathing pool where lovers would meet, a temple with its intense mixture of fragrances from all the offerings, and the aromas of mummies and coffins. “When you open a book [on ancient Egypt], you normally see some black-and-white pictures, sometimes in color, but it’s always a visual experience. I wanted to do something using a different sense – and the sense of smell is very powerful,” said Goldsmith.

Impossible recipes

Goldsmith says that the process of recreating these products has great value beyond the final result. By making these recipes herself, she gained other insights from the process, such as the physical labor involved in grinding ingredients with a stone mortar. She realized that the perfumers of ancient Egypt were not dainty, effete artists, but skilled and robust artisans who made high-quality products.

Goldsmith also discovered that these ancient Egyptian recipes always leave out some piece of information, either about the equipment used or about an ingredient. She once realized that a recipe could not be made the way it was described. “I guess they did this on purpose,” she said. “Making perfumes for the gods was a very secret process, so they wanted to maintain the secret but also document the process. The best way to do that was to document it in a way that is very difficult to understand.”

This is why Goldsmith thinks that some aspects of the recipes will always remain a mystery. “It’s never going to match 100%, but I don’t think that’s the goal of recreating a perfume. I think the goal is to get as scientifically close as possible, and do the best I can to recreate the olfactory history of ancient Egypt so that people today can experience that period in a new way.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.