Cabrillo National Monument in California: Spain and Portugal in face off over the origins of explorer

A monument erected early in honor of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, the first European explorer to set foot in San Diego Bay in 1542, is causing a diplomatic headache

Is it Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo or João Rodrigues Cabrilho? This is the question those responsible for the Cabrillo National Monument are currently wrestling with.

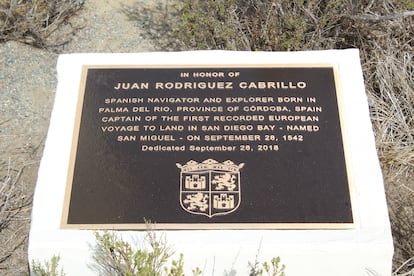

The monument was erected early last century in honor of the first European explorer to set foot in San Diego Bay in California in 1542 and the “temporary” response to the conundrum has been to return the 2018 plaque stating that Cabrillo was originally from Palma del Río in the Spanish city of Córdoba to the Casa de España association. But the two metopes stating he was born in Portugal remain, as well as one placed on the site in 2003 referring to his Spanish origins.

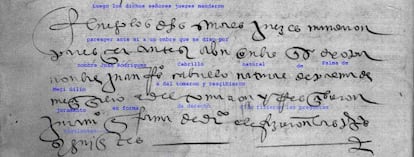

The Portuguese insist on the explorer’s Portuguese roots on account of a document signed in the 17th century by the royal chronicler Antonio de Herrera, which was written 60 years after Cabrillo’s death. Meanwhile, the Spanish contingent point out that Rodríguez stated on several occasions under oath that he was from Cordoba, proof of which can be found in literature stored in the Archive of the Indies in Seville, New York and Guatemala. Palma del Río town council and the Casa de España are now requesting the intervention of the Spanish government to put an end to this “nonsense generated by the pressure of the large Portuguese community in California. João Rodrigues Cabrilho never existed,” they say. Diplomatic sources say that a complaint will be submitted to the Department of the Interior in order that the plaque be replaced and “the truth acknowledged.”

The monument to Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo was erected in 1949. In 1966, the surrounding park was listed on the US National Register of Historic Places. In fact, its official website states that “the conqueror was born in Spain” and fought the Aztecs under the orders of conquistador Hernán Cortés. The website also mentions that after 103 days of travel during which he headed an expedition in search of possible settlements on the West Coast, he reached Ballast Point in California “where he claimed the land for the Spanish crown, because at that time there was no European settlement in the area.”

Hence, Rodríguez founded the city of San Diego, which was initially known as San Miguel. The expedition then continued north, only for Rodríguez to die of a wound on January 3, 1543. The remaining members of the expedition continued, however, until reaching Rogue River, in Oregon, before returning to Mexico.

It is known that Rodríguez Cabrillo was born in Spain because he said so himself when he was interrogated about the disappearance of 1,000 pesos of gold stored in the chests of a galleon. Under oath, he claimed to have been born in Palma de Micer Gilio, now Palma del Río, according to documents found in 2015 by Dr. Wendy Kramer, a Canadian researcher at the UK University of Warwick, in the Archive of the Indies in Seville. Kramer also says that this finding has been corroborated by other material she recently located in the Hispanic Society in New York, in the Provincial Historical Archive of Seville and in the General Archive of Central America, in Guatemala, all of which “prove that he was born in Palma del Río. Rodríguez declared that he was from Córdoba before Spanish officials in Cuba, the Canary Islands and Seville. Why would he lie, knowing that this could mean jail time? And what would be the point, given it was many years before founding San Diego?” says Kramer.

Spanish diplomatic sources stress that the controversy has nothing to do with “historical revisionism, but rather a local clash of interests. It is a complex issue given our friendly relations with Portugal, but he was certainly Spanish,” says one. According to these sources, the park authorities have tried to please both sides, “introducing a mention of possible Portuguese origins in its museography, something that has been completely ruled out after Kramer’s discovery. Let’s just say that California’s Portuguese contingent is the most important in the United States, financing local events and parties in memory of a supposed Portuguese Cabrillo, so the park has rolled over.”

Meanwhile, the mayor of Palma del Río, Esperanza Caro de la Barrera, recalls that in 2018, three years after Kramer solved the mystery of Cabrillo’s origins, the then-mayor, José Antonio Ruiz Almebara, attended the inauguration of the plaque in San Diego and noted the “immense joy of the Hispanic community, but not so much of the Portuguese, who have been creating a version of a João Rodrigues Cabrilho since the early 20th century that has nothing to do with the historical figure. We have noticed there have been political difficulties in recognizing a scientific truth from the start,” adds Caro de la Barrera. “We have tried to be cordial and have been very respectful throughout the process. We are uncomfortable with the removal of the [2018] plaque, and feel for the men and women of the United States who have always maintained that Cabrillo was Spanish.”

Meanwhile, Córdoba city council is going to ask the ambassador and the government to take a stand “because, although a plaque can be removed, the truth cannot; the truth is unalterable.”

However, the Portuguese researcher João Soares Tavares claims that the explorer was born in his country, in a small village, near the border with the Spanish region Galicia, called Lapela and that his original home is still standing. In an article published in January 2022 in the magazine Ecos de Barroso, Soares explains that he arrived in this village by chance and discovered that Rodríguez emigrated to Galicia when he was young. “At the time, Lapela was a village of shepherds belonging to the parish of São Lourenço de Cabril,” he says. “Both the Portuguese and Galicians grazed their livestock freely in the same mountains. It is possible that a Galician settled in Lapela de Cabril and married a Portuguese woman. In order to identify the house where the couple lived, the neighbors called it Casa do Galego. At the end of the 15th century and beginning of the 16th century, João Rodrigues was born.”

Soares maintains that a letter from Cortes sent to Charles I on October 30, 1520, refers to three soldiers by the name of Juan Rodríguez. In order to distinguish himself from his namesakes, the explorer added the surname Cabrilho or Cabrillo to his name. Where did he get it from? Soares believes it is clear that it corresponds to the toponym of the parish of Cabril to which the hamlet of Lapela belonged. “He was registered and baptized in the church of Cabril, although we cannot confirm this because the parish books of the 15th and 16th centuries have disappeared,” he admits. However, Soares shores up his claims by pointing out that the chronicler of Castile, Antonio de Herrera (1549-1625), referred in his General History of the Deeds of the Castilians in the Islands and Ocean Mainland “to the Captain Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, Portuguese and somebody well-versed in matters of the sea.” This statement, as refuted by Kramer in her book Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, the Spaniard who Explored California, was made 60 years after his death. “It is clear that Herrera was wrong,” she says. “Rodríguez was of Moorish descent, as his surname Cabrillo indicates, which is why he sometimes signed his name as Rodríguez de Palma.”

Historian at San Diego University, Iris W. Engstrand, stated in a letter to US Secretary of the Interior, Debb Haaland, last May that this controversy originated in 1934 when Colonel John R. White, superintendent of Sequoia National Park, made a “dramatic change” in Cabrillo’s nationality, making him Portuguese, because “he realized that there was virtually no Spanish community in San Diego. From then on, he took advantage of the moment to reinterpret history, introducing the falsehood that Juan Rodríguez was Portuguese. Until then, he was known as a Spaniard, as recorded in the history of San Diego.”

“Now the National Park Service at Cabrillo National Monument has updated its museum, which falsely explains that a Spaniard named Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, or a Portuguese named João Rodrigues Cabrilho, was the first European to sail into San Diego Bay on June 27, 1542,” adds Engstran. “But the Portuguese individual known as João Rodrigues Cabrilho is a fictitious name and does not exist.”

Engstrand also calls on the US Congress to “right the wrong” already flagged up by researcher Susan Collins in her An Embarrassment of Riches. The Administrative History of Cabrillo National Monument, “which shows that the National Park Service misrepresented history and heritage just so that the local Portuguese could sponsor a festival” at the Cabrillo monument.

Meanwhile, Andrea Compton, superintendent of the Cabrillo National Monument, describes the removed plaque as a “temporary” measure in a recent letter sent to the Casa de España. Compton states that the data confirmed by Kramen is already reflected not only on the park’s website, but also in brochures, educational programs and even in a documentary, “but the new signs will also reflect how our knowledge of history changes and will better explain the statue and the nearby Spanish and Portuguese naval plaques.” EL PAÍS has not been able to talk directly to Compton.

Jesús Benayas, president of Casa de España, which has the support of The Hispanic Council – an entity that promotes cultural relations between Spain and the US – is upset by the saga. “Rodrigues Cabrilho neither exists nor has ever existed,” he insists. “It is an invention of the 1930s. Of the four plaques that surrounded the statue, three have been moved, and ours, where his Spanish nationality was stated, has been returned to us. They say it was a temporary plaque. That is absolutely untrue. The consulate, the embassy, the Spanish government has to intervene and not allow itself to be walked all over. The truth is the truth. It is the history of San Diego, of California, of the United States and also ours.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.