The forgotten Spanish diaspora in the US

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, tens of thousands of Spaniards migrated to the US. They worked in tobacco companies, factories and mines. They settled in every corner of the country, from California to Hawaii, Florida to Ohio. James D. Fernández, a descendant of such migrants, has spent the last 10 years compiling the experiences of these pioneers

During a heated debate on immigration in December 1920 in the House of Representatives, Washington D.C., Congressman Harold Knutson took the floor and launched into a diatribe.

Born in Norway, Knutson ranted about a certain type of foreigner who, in his view, came to the US to steal American jobs and spread radicalism. He said that the previous day he had been at Ellis Island, the point of entry for immigrants coming to the US, and had seen 2,000 people arriving from a certain dangerous country: “Spain is a hotbed of anarchy. And the Spanish government is rounding up all these anarchists and dumping them on the United States.”

Spain? Was there really ever a mass exodus of Spaniards to the US? Knutson was offering a warped view of one of the most fascinating and little-known episodes in these two countries’ shared history.

It is true that at the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th, tens of thousands of Spanish workers and peasants settled in tight-knit communities across the length and breadth of the US. Not unlike the Spanish communities in Cuba and Argentina, these Spanish enclaves strengthened thanks to local information networks back home where word would spread of job opportunities across the Atlantic.

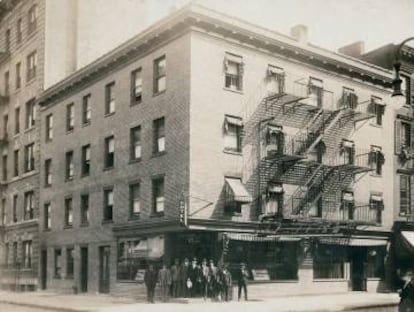

Consequently, at the start of the 20th century, you would find migrants from Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria in cigar factories in Florida; migrants from the Basque Country, Aragón and Castile working on ranches and in the restaurant and hotel trade in the southeast and mountainous west. Meanwhile migrants from Andalusia, Valencia, Extremadura and Castile could be found in the sugar plantations of Hawaii and in the jam, dried fruit and fish factories of California. In New England, there were migrants from Cantabria working the stone quarries while others from Asturias, Castile, Galicia, Valencia and Andalusia made their living in the mines and in the factories of the northeast and midwest industrial belt. And in New York, the gateway to the New World, there were migrants from all over Spain, mainly working in the port and on ships, but also in a variety of trades and business from the sale of cigars to domestic service.

Among these pioneers were José and Carmen, both from Asturias. They met the same year Knutson delivered his diatribe, at a picnic organized by the Asturias Center in New York. Sitting in a park in Staten Island within view of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, Carmen and José practically had to shout to be heard over the noise made by their compatriots and the bagpipes, both hallmarks of such occasions.

The Spanish government is rounding up all these anarchists and dumping them on the United States

US Congressman Harold Knuster

Carmen, 18, told José that she had just arrived from Sardéu, Ribadesella, to join her sister who had lived in the city for some time and had managed to get her a job in Brooklyn as a nanny. Dressed in a light linen suit and a jaunty Panama hat, José, 31, told Carmen he was born near Avilés and was also a recent arrival, though he had already been to Havana, Cuba and Tampa, Florida. He took out his wallet and fished out his card, recently printed, which read José Fernández Álvarez, tobacconist. “We are going to try our luck here,” he told her. “But English is such a hassle. You don’t need it in Tampa. How are you getting on with it?” Carmen laughed and said, “Really badly. I only know one sentence, which I was taught at the hostel and I can’t even say that.”

“Let’s hear it!” José insisted until, blushing and without taking her eyes from his card, she delivered the words: “My room is number 7.”

José Fernández Álvarez and Carmen Alonso Mier are my grandparents. Carmen told me about how they met just once – laughing as she did and reproducing the exact conversation. That was just before she died in 1984, a few months after José, a charismatic and imposing figure, had himself passed away. And I can date the conversation exactly because any autobiographical details from my grandmother were gleaned in that brief period between José’s death and her own. The day we buried Carmen in a New York cemetery beside José, I thought about the anecdote and wondered how those two migrants from Asturias would have reacted if someone had told them during that picnic that they would live together for the rest of their lives in Brooklyn and be buried together in New York by their five Spanish-American children and more than 20 grandchildren who were completely American...

Fifty years after the picnic and Knutson’s scaremongering, I went to school and learned how to say, “My room is number 7” in Spanish. My mother’s family was originally from Ireland and we only spoke English at home. My grandparents seemed proud and bewildered by my growing interest in the country they had left behind forever. When I told my grandfather I was thinking about doing a PhD in Romance Languages, he replied, “Ok, but what can you make with that?”

Well, I made a career out of it: 20 years of writing articles and books and giving classes and conferences. During my first 20 years as a university lecturer, I kept my personal family background strictly separate from my research and lectures. I frequently read and taught Poet in New York, for example, but it never occurred to me that Federico García Lorca and my grandparents had been breathing the same polluted air during the months the poet had spent in the city between 1929 and 1930. As far as I was concerned, they moved on different planes – one belonging to the realm of culture, history and universal matters and the other to the purely personal – worlds apart.

An assignment in 2006 was the first step towards reconciling the two. The Museum of the City of New York had asked me for a report on how Spanish migrants in New York had reacted to the civil war back home for an exhibition titled Facing Fascism: New York and the Spanish Civil War. I started to study the local newspapers that were written in Spanish during the period and came across long lists of Spanish emigrant associations that had come together under the umbrella of the Confederated Hispanic Societies in a bid to coordinate their efforts to support the Republic. These lists revealed the existence of Spanish communities around the country, each one with its picnics and emigrant grandparents.

I also carried out interviews with the older generation – my parents among them – who still had vivid memories of those years of conflict and solidarity. I soon realized that the vital material needed to build an accurate picture of this unforgettable diaspora was in a precarious state, on the verge of being lost forever from private homes and the minds of the emigrants’ descendants.

Around that time, I met a documentary maker named Luis Argeo who had just made AsturianUS, a movie about Asturias immigrants living in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. Argeo had arrived at the same conclusion as I had concerning the value and precarious state of this little-known episode in Spanish-US history. We decided to collaborate. We used GPS to map the lists of Confederated Hispanic Societies and, with portable scanners, cameras and microphones, we visited the descendants of Spanish immigrants across the US.

The protagonists of this story that took place more than a century ago are no longer with us. Their children, if alive, are 80 or 90 years old. Generally, they remember a smattering of Spanish from their childhood but don’t use it much. They often welcome us into the modest homes they inherited from their parents, still filled with knickknacks, photos and smells that evoke the first generation. But when it comes to the grandchildren or great-grandchildren, the homes are almost always bigger and airier, with more light and less history. The grandchildren rarely speak Spanish, which means most of their family archives are a mystery to them.

Our visits would last an entire day. Besides filming in-depth interviews, we stored the family archives in digital format. And in almost every home, we were invited to enjoyed a traditional Spanish meal. Over a period of 10 years, we were treated to: paella in Monterrey, California, made by the son of immigrants from Alicante; filloas (crepes) in Astoria, New York, from the daughter of couple from A Coruña; homemade spiced sausage smoked in California by the grandchildren of Andalusian locals; gazpacho in California from the granddaughter of migrants from Almeria and Malaga; fried hojuelas (similar to French toast) in Hawaii made by the granddaughter of migrants from Avila and dozens of versions of Spanish omelet and chicken with rice in West Virginia, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Sometimes, we managed to coordinate our trips to coincide with group activities organized by the descendants, such as the unforgettable picnic held in a huge park on the fringes of Canton, Ohio. Kathy Meers, née Pujazón in 1952, brings along a large pan of rice and chicken and a stack of Andalusian pastries known as pestiños as well as two plastic bags filled with photos and documents. While we help her unload her car, she says, “I am told that Spanish was my first language because I lived with my grandparents until the age of three. Later, at school, I forgot it.”

The Spanish Civil War marked a point of no return in the lives of the diaspora

These grandparents – Juan Pujazón Valencia and Adelaida Justo Blázquez – were originally from Nerva in Huelva. They landed at Ellis Island in November 1920, around the time that Knutson made his visit to the immigration center.

A strike in the Riotinto mines in 1920 pushed hundreds of workers, including Juan and Adelaida, from Huelva to Canton in search of work in the steel mills. These miners joined up with a community from Asturias, which had settled there shortly before. Canton was already a big industrial center for immigrants from all over the world. That same year the city would give birth to the National Football League.

At the picnic, Kathy doesn’t stop. She welcomes the families and lays out the food on two big tables. And she promises to show us the contents of the bags after we eat. “I don’t want to get the programs dirty,” she says.

This diaspora would gradually cement as the Spanish empire crumbled and the US became an industrial power with imperial ambitions. The flood of migrants peaked during the First World War. Spain remained neutral during the war and this stance, combined with labor demands in the US as Americans were drafted, led to a surge of Spanish immigration to the United States. But numbers would plummet shortly after Knutson’s speech, thanks mainly to the lies and fears behind it.

Because the truth is that the Spanish government never arranged for its most problematic citizens to be shipped out to the US; nor were those migrants mainly anarchists; and at no time did 2,000 Spanish migrants land all at once on Ellis Island, nor anything even approaching that figure. But Knutson’s words fell on fertile ground. The economic recession after the end of the First World War and the notorious Red Scare were enough to foster anti-immigration ideologies and movements, headed by people like Knutson.

In the early 1920s, shortly after Kathy’s grandparents and my own arrived, a series of immigration laws were introduced with the aim of curtailing immigration from southern and eastern Europe, where the “bad hombres” of the time came from. This xenophobia culminated in the National Origins Act, passed in 1924, which was based on a national origin quota and stipulated that only 131 Spaniards could legally enter the US that year – not even enough for a decent country picnic. With these quotas, Knutson and those who identified with him were able to build – with figures and prejudice instead of bricks and mortar – a wall between Spain and the US .

The National Origins Act practically put the brakes on legal immigration from Spain but the 1920s would prove to be a decade of consolidation for the communities that had already settled in the US. The Hispanic American Center in Canton, which organized this picnic, for example, was established in 1925.

We move from table to table, trying out different dishes, including tuna pie with the Guerra family, cod with the Prendes, flan with the Condes and rice pudding with the Cabos, and we talk about how these dishes have evolved with the diaspora. We also chat with the descendants and film a few interviews with the idea of documenting how they perceive their ancestors’ stories.

At the picnic, we notice a tendency we have seen in other families – a tendency to make family histories appear more American. Often, despite the evidence from the family archives, there is an American Dream quality to the stories that depict their forefathers as solitary heroes in the image of the archetypal self-made American man. It is as if they are saying, “My grandparents came alone, they didn’t know anyone and nobody helped them. They came in legally and they always obeyed the law. They were never interested in politics, they only focused on their work. They left Spain with the intention of remaining in the US and becoming US citizens. They loved this country even before they got here.”

It is evening by the time we get back to the Pujazón clan. Kathy is hauling photos out of the plastic bags and arranging them on the table that has been cleared for that purpose. There is a photo of her grandfather dressed as a bullfighter and group shots of picnics from long ago. But what catches our attention is a collection of pamphlets laid out at the other end of the table. “My grandfather collected all the printed programs for this annual lunch from 1936 to 1973. I inherited them,” says Kathy.

The two that stand out from the rest are the programs for 1937 and 1946. In a curious way, they offer the key to interpreting this diaspora’s history. The first, written in Spanish, was designed with one eye on Spain and is the product of a community that lives between two countries. The second is in English and shows a happy family, with a dog, that seems to be marching resolutely towards complete assimilation into American culture.

The juxtaposition of the two pamphlets confirms something that the descendants’ archives suggest again and again – that the Spanish Civil War marked a point of no return in the lives of the diaspora. The assimilated descendants talk about their grandparents’ epic adventures; they tell of self-made individuals who left their villages and towns in 1910 and 1920 supposedly knowing what their futures held and that they and their children would be American. But they couldn’t say why their parents waited 20 or 30 years, until 1939 and 1940, to apply for US citizenship. Perhaps the descendants simply don’t see it, but the contrast between the two picnic programs, as well as the photos, letters and newspaper clippings from the family archives, says it for them: the war and the fallout from the war put an end to the very present dream of ever returning to Spain, and began a process of forgetting.

Once there is no way back, everything changes for an immigrant – their relationship to the host country and to the country they have left behind; the priorities bringing up children who will now be Americans; the photos that are kept and, above all, the stories that are made about them.

If, in that other picnic in Staten Island in 1920, José and Carmen were to have seen their future, they would not have believed it. Guessing what is ahead is hard but understanding the past without myths and legends is equally so. Would those two young people recognize themselves in the providential stories their descendants have made up about them?

In the last presidential elections, Donald Trump was swept to victory in County Stark, Ohio – Canton’s county. How is it possible, in a country of immigrants like the US, for there be an anti-immigrant trend strong enough to put Trump in the White House? Could the way the descendants remember the original Spanish immigrants offer a clue?

We often expect there to be a natural empathy between those who are descended from immigrants and those who are immigrating now. But for there to be empathy, there needs to be acknowledgment that the two experiences are, if not the same, at least comparable. And many descendants reject such comparisons; they resist identifying with those who are currently knocking at the door. I wonder if they don’t do so on account of the false memories and stories that allow them to build walls more insurmountable than those of Knutson and Trump in the face of the anguish and yearning of others.

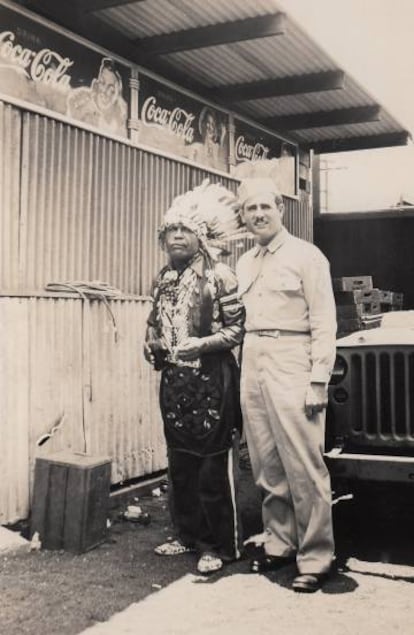

James D. Fernández is a lecturer at New York University and co-author with Luis Argeo of Invisible Immigrants: Spaniards in the United States, 1868-1945, the source of the photos used here. He has also been consulted for the new María Dueñas novel, The Captain’s Daughters, set in a community of Spanish emigrants in the US in 1936.