Today’s leading Tik Tok influencer creates fashion parodies from one of the world’s poorest islands

With his sendups of fashion shows, Shaheel Shermont Flair is TikTok’s star du jour. However, it’s worth going beyond the layers of the racialized and gay content creator’s mockery and irony to get at the real meaning of his creative expression, which is now going viral

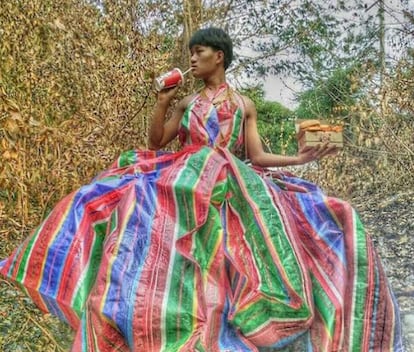

Shaheel Shermont Flair is 24 years old, and he wants to be a comedic actor. On his social media, where he showcases his talent for comedy through videos/reels, he describes himself as a “public figure” and “artist.” On June 20, he shared his latest witty idea online: a fashion show parody. “Fashion shows be like this,” he declared (alongside the emoji of a face crying with laughter). Then, barefoot and dressed in a T-shirt and sport shorts, he started walking like Linda, Naomi, or Christy through what looks like the backyard of his house. Each trip displayed a style created with all sorts of knickknacks, junk, utensils and household furnishings. In an unintentionally Rickowensian moment (or not), he even used his little sister, Riharika, who was accessorized and off to the side, as a complement. On TikTok, where he has been appearing as @shermont22 for a little more than a year, the short video has racked up over five million views and counting. He continues to gain followers as well; he has nearly 350,000 right now and 13 million or so “likes.” Viewers keep asking him for more. At popular request, he uploaded his most recent video a few hours ago. It is the ninth installment of a viral saga that, in reality, is not so ironic and hilarious.

By today’s standards, Shermont is already a star in terms of fame and glory. In a recent story on his Instagram profile (@shermont_22, which has considerably fewer followers, although one assumes that his viewership there will eventually grow), he confessed to having googled his name and was in disbelief about how far-reaching his performance was. “I’m in the news!” He was amazed and posted screenshots from different digital media, especially from Southeast Asian outlets. On Twitter, he is being hailed as the week’s hero for making fun of, mocking, and deriding that silly and increasingly absurd thing: fashion (of course).

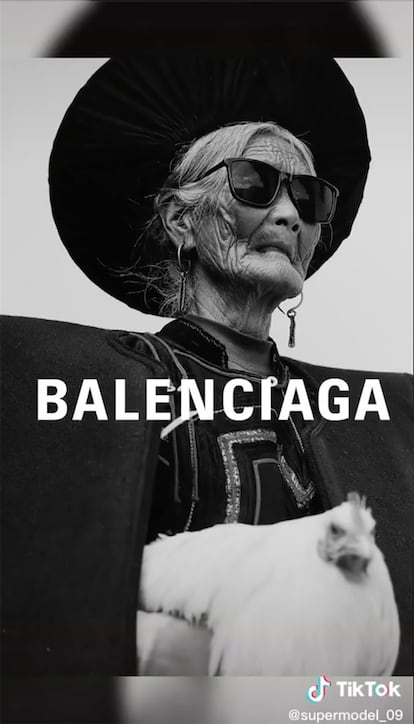

The same thing happened just two months ago, when a video on Douyin (a social network) went viral on its Western counterpart, TikTok, giving rise to the turn-your-grandmother-into-an-international-supermodel challenge. In the video, a venerable elderly Chinese woman was dressed as the personification of Balenciaga, Gucci and Prada by a little boy (presumably her grandson) with what he had on hand in his yurt, including chicken. The results of the challenge—images done in the style of luxury advertising campaigns with brand logos superimposed on them—tell us that we are all Demna Gvasalia, Alessandro Michele, or the tandem Miuccia-Raf Simons, or at least we can be.

For a long time, people have complained repeatedly about how bad fashion is, now more than ever. Not only does fashion pollute the planet and exploit its workers, but it also mocks consumers. Are these designers crazy? No, they are just pulling our leg with so much aesthetic arbitrariness/ugliness/stupidity. It’s only fair, then, to return the favor in jaw-droppingly funny ways. In fact, trolling the fashion industry—like Shermont and the Chinese grandmothers (there are quite a few of them)—may be evidence of a certain social disgust with its three-ring circus and its trainers, illusionists, and clowns, whose extravagances are understood as nonsense and, even worse, insults or near-insults. Vetements’s DHL uniform. Virgil Abloh’s Ikea bag. JW Anderson’s broken-skateboard-encrusted sweater. Balenciaga’s shredded sneakers. All of Balenciaga, the brand inevitably referred to in comments on the young comedian’s reels. There are more than a few comments that also praise Shermont’s attitude and stylish model’s trot; they ask to see his fashion show in Paris and Milan. And then there are those who attempt to be funnier and more sarcastic and ironic than the video itself, which is typical on Twitter. But none of the comments have taken issue—or even tried to take issue—with the video’s deeper premise.

Shaheel Shermont Flair is a Fijian of Indian descent; his ancestors were Indian Girmtyas who went to British-colonized Fiji in the mid-19th century as slave labor. He is also gay. “Welcome the queen to Instagram,” he urged in April 2021, when he debuted on the social media site. In November, he posted that “[m]y sexuality isn’t the problem, your bigotry is.” In April of this year, he returned to the fray: “There are those who hate me for being different and not living by society’s standards, but deep down they wish they had my courage.” Before his phenomenal fashion show, he was already doing “low cosplay” of Indian women by using waste—toilet paper for the sari, a bottle cap for a nath on the nose, and a tea bag for the maang tikka on the forehead, for example—to create an Indian bride’s trousseau in the playful post, “Getting ready for my lover.” In another, he straps on two water-filled balloons as swaying breasts under his T-shirt. “The things I do for TikTok,” he wrote. Indeed, Shermont has made comedy his path to escape bullying and discrimination (prejudice is double in his case) and turned his social media accounts into a highway to heaven. Just like Apichet Madaew Atirattana did back in his day.

Except for its glamorous intent, everything about Shermont’s catwalk recalls that of Thai Dovima. In 2016, before Tik Tok’s one-track mind took over, a teenager from the rice-growing region of Isaan—one of Thailand’s poorest areas—astonished the world by turning everyday objects, twigs, and trash into fabulous outfits. He filmed himself modeling those clothes at different locations in his village; his grandmother acted as a styling assistant. Facebook and Instagram went wild over what was termed the “breakdown of barriers between gender identity, fashion and recycling.” At the time, Madaew (a nom de guerre) explained it this way: “I want people to see that ugly things that don’t fit in can be transformed into something beautiful. And that dressing well is not about money.” Just a few months later, Asia’s Next Top Model, the South Asian edition of the US talent show, called him to be a guest designer during the program’s fourth season. The following year, Time magazine put him on its list of new generational leaders. His example spread. Soon, new stars made their appearance: Suchanatda Kaewsanga, a fellow Thai who is openly trans, and the Chinese Lu Kaigang, whose offerings for fashion shows in his village—located in Guangxi province—unironically included dresses made of garbage can lids and old air-conditioner bags.

All this can be viewed as a response from the poor and marginalized to fashion’s global impact as a mass phenomenon ascribed to the culture of leisure/entertainment. It is a practice that resonates with the button-down politics of Patrick Kelly, the first African American designer to join the ranks of the Parisian ready-to-wear trade association in the mid-1980s; the clothing activities of the Swenkas (workers of Zulu origin) and Skhothanes (post-Apartheid image-obsessed youth) in Johannesburg; and the young Ghanaians who exploit the city-sized textile dumps surrounding the capital, Accra, as sources for their creativity.

The narratives of the designers who establish the industry’s current direction, amplified as never before by digital media, also show that it is indeed possible to dress as stylishly as Balenciaga, Gucci or Prada without breaking the bank. That’s why TikTok’s Chinese supermodel grandmothers reflect aspiration and not scorn; they are proof that fashion has something for everyone, even the most socially disadvantaged (one can’t miss the proud hashtag that usually accompanies them, #chinastreetstyle). That’s why Apichet Madaew Atirattana, Suchanatda Kaewsanga and Li Kaigang have made careers as creators, bloggers or influencers with hundreds of thousands of followers. They’ve come so far, propelled by the dreamy fuel that the magazines in village hair salons and satellite TV offer. “It’s very easy to blame fashion for all the problems it creates, but I’d like to think it’s also capable of helping people in many ways, in positive ways,” says Minh-Ha T. Pham, a professor of media studies at Pratt Institute in New York and the author of Asians Wear Clothes on the Internet (2016), an essay about the dynamics of race, gender and class among the young Asians who have found a way to express their identity through fashion, and in the process pushed the system to finally recognize them as a socioeconomic and cultural force.

Shaheel Shermont Flair laughs, but he does fashion shows because he also knows what fashion can do for his ambition to become an actor.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.