When Spain’s Julio Iglesias conquered the US

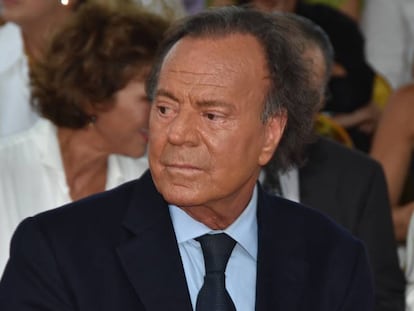

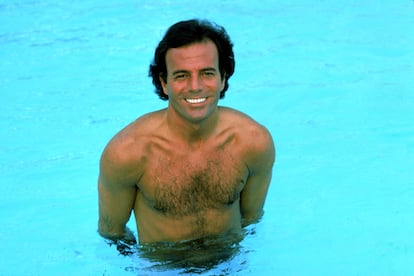

A new book by Hans Laguna documents the formative years of the Spanish artist and his rise to global fame

One day in August 1986, two men dressed in black arrived at the Pikes Hotel in Ibiza, in Spain’s Balearic Islands, where stars such as George Michael, Grace Jones and Freddie Mercury used to stay. The men said they represented a “very famous” singer who wanted to be by himself for a few weeks: Spain’s iconic pop star Julio Iglesias. The singer needed eight rooms (the hotel had 20), and he wanted them for the next day: he would fly on his private plane to the island after a concert in New York. In Ibiza, he traveled in a caravan of five white cars, and rented a yacht, a sailboat and a speedboat. Iglesias swam in the morning, sunbathed on the high seas, and received a visit from ¡Hola! magazine. Every day, he ate Galician seafood prepared by private chefs. He was surrounded by women, who came and went to his bungalow via a private entry. The Pikes Hotel was legendary. “If you had a drink at the bar, you were likely to find a line of coke. Does that mean we were we selling? Not at all. Maybe that little extra came with the drink,” said its owner, Tony Pike. Julio Iglesias won over the local authorities. Even a Civil Guard officer – who was investigating the hotel for possible drug trafficking – went to Freddie Mercury’s 41st birthday party, a celebration that lasted several days and ended in a bill that included 350 bottles of Moët Chandon and 250 broken glasses.

Julio Iglesias sailed through it all without letting it affect him. That’s according to a new book called Hey! Julio Iglesias y la conquista de América (or, Hey Julio Iglesias and the Conquest of America) by musician and writer Hans Laguna. Everyone cited in the book agrees that the singer had no interest in cocaine, and that he made a superhuman effort to meet his media commitments – he always showed up, whether or not he slept the night before. Laguna’s 430-page book takes a look at these decisive years, between 1983 and 1985, when Iglesias was at the peak of his career and about to conquer the US market.

What emerges from the exhaustively researched book is a person obsessed with fame who was desperate to work all over the world. Everything was happening at that period – albums, concerts and a relentless promotional campaign. It was the groundwork that would go on to make him one of the most commercially successful Spanish singers in the world, with more than 100 million record sales to his name. Iglesias himself admitted to being hooked on fame – “if fish could clap, I would sing at sea,” he once said. While his right-hand man, manager Alfredo Fraile said: “He suffers from a sick addiction to success.”

“The origins of this obsession go back to his childhood,” says Laguna in Barcelona. According to the author, Iglesias’ parents weren’t happy together, and he learned how to read their reactions in order to please them. “In his adolescence, this ability to interpret the demands of others, combined with the desire to stand out. First, as a goalkeeper and then – after an accident that almost cost him his life, ending his career at Real Madrid [soccer team] – as a singer,” Laguna explains. In the book, Spanish singer Ramón Arcusa tells a story that highlights Iglesias’ discomfort with anonymity. When he settled in Miami, shortly before buying his first private plane, “Julio stopped many women at the airport, asking them with a smile if they knew who he was.” Almost every Latin American woman knew, but hardly any of the Americans did.

“Julio always offers the same version of himself, which is also his best version,” says Laguna. He has three maestros: Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Elvis Presley. “They have style. You recognize them at the first beat,” said Iglesias on one occasion. “When the style is there, the voice is secondary. The voice does not have to be perfect. A cold, perfectly tuned, long note has no emotion or meaning. The voice should be personal.”

According to Laguna, Iglesias’ style stemmed from his ability – not only to avoid trouble – but also to use “his vocal technique to make the difficult seem easy.” And that’s why hits like Me olvidé de vivir (or, I forgot to live), Hey and De niña a mujer (or, From girl to a woman) cover at least over an octave. “This range is far from what singers with enormous tessituras such as Axl Rose or Mariah Carey can cover. But if you start singing the songs, you will discover that you have to shout to reach certain notes that Julio attacks without flinching and without using falsetto,” writes Laguna.

In 2017, after years of media attention, Iglesias admitted to saying “a lot of nonsense,” explaining “they interview me every day and it’s impossible not to say [nonsense].” When the singer looked back at this time, when he was wining over the US market, doing ads for Coca-Cola and living on 1100 Bel Air Place – the title of his first album in English –, he described them as the most hectic stage of his career, a time when he was “very naughty” and was somewhere “between an asshole and playboy.” In an interview with Spanish national TV broadcaster TVE, Iglesias even said he wanted his epitaph to be: “He stopped dreaming when he could buy his dreams.”

The album 1100 Bel Air Place was recorded over 16 months in nine studios. According to Laguna, nine music arrangers, 12 sound engineers and 79 instrumentalists were involved in the record. “Modern music has a homeland in today’s world. And that country is the United States. Now, you have to sing in English to get there, where I want to be,” Iglesias said on one occasion. “I belong to the country where I sing. If they ask me where am I from in China, I will say I’m Chinese.”

The book documents the Spanish artist’s rise to global success. It presents reflections and insights from musicians, managers and other members of the singer’s inner circle. As Iglesias himself once said: “Life has been very generous with me, and the light has struck me like a deer in the headlights.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Oona Chaplin: ‘I told James Cameron that I was living in a treehouse and starting a permaculture project with a friend’

- Pablo Escobar’s hippos: A serious environmental problem, 40 years on

- Chevy Chase, the beloved comedian who was a monster off camera: ‘Not everyone hated him, just the people who’ve worked with him’

- Why we lost the habit of sleeping in two segments and how that changed our sense of time