El Niño weakens but global temperatures remain at record highs

February is also shaping up to be the warmest in history, according to data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service

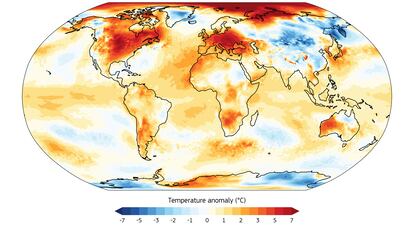

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) believes that El Niño, a natural pattern that causes water surface temperatures in tropical areas of the Pacific to rise, peaked last December and is now gradually weakening. “But it will continue to impact the global climate in the coming months, fuelling the heat trapped by greenhouse gases from human activities,” warned the WMO in its latest update. Last February, in fact, is shaping up to be the warmest February on record. The previous record was set in 2016, coinciding with another significant El Niño event.

The WMO update estimates “there is about a 60% chance of El Niño persisting during March-May and 80% chance of neutral conditions (neither El Niño or La Niña) in April to June.” El Niño occurs periodically — every two to seven years — and usually lasts between nine and 12 months. “It is a naturally occurring climate pattern associated with warming of the ocean surface in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean,” the WMO explained. And it influences weather conditions and storms in different parts of the world.

The current El Niño began in June and helped make 2023 the warmest year on record. However, it was not the main cause. The greenhouse gases emitted by the world economy are what have led to the continuous rise in global temperatures, a trend that has become more pronounced over the last decade.

“Every month since June 2023 has set a new monthly temperature record — and 2023 was by far the warmest year on record. El Niño has contributed to these record temperatures, but heat-trapping greenhouse gases are unequivocally the main culprit,” explained WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo in the update.

The surface temperatures of the Pacific Ocean in the tropics were above normal, a clear sign of the effect of El Niño. But, as Saulo warned: “Sea surface temperatures in other parts of the globe have been persistently and unusually high for the past 10 months. The January 2024 sea-surface temperature was by far the highest on record for January. This is worrying and cannot be explained by El Niño alone.”

Last January was the warmest ever on Earth since reliable records began in the mid-19th century (although paleoclimate scientists argue that you have to go back several millennia to find such high temperatures). And last February also looks set to break records, according to data provided by Climate Pulse, a tool from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) of the European Commission. Climate Pulse — which provides a daily average temperature — indicates that this past February was around 0.2 degrees Celsius warmer than 2016, which held the previous record.

The first two weeks of February were especially warm across the planet, as reflected by Climate Pulse data. Temperatures eased in the second half of the month, although they have continued to be among the highest in historical records. This data must still be reviewed and verified by the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

In addition to contributing to rising global temperatures, El Niño is associated with increased rainfall and flooding in the Greater Horn of Africa and the southern United States, and with unusually dry and warm temperatures in Southeast Asia, Australia, and southern Africa, according to the WMO. The latest event has also exacerbated drought in northern South America and contributed to drier and warmer conditions in parts of southern Africa.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.