The books that lay hidden behind a wall for five centuries in Spain

Two decades have passed since the discovery of the manuscripts that the imam of Cútar hid in a wall in his home around the year 1500, one of them an Almohad-period Koran

Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār knew astrology, mathematics, and poetry. He was an expert jurist and was interested in the superstitions and news of the turbulent times in which he lived. “In all the world it never happened / what happened in Al-Andalus,” he wrote in one of his poems. A prisoner for years in Seville, he copied books for the city’s governor, until he was released and appointed alfaquí — expert in law — and imam of Aqūṭa, as today’s Cútar was once known. The municipality in the district of Axarquia in Málaga province with a current population of 600 was, at that time, just a rural farmstead of similar size. He arrived there on August 9, 1490. He recounted his daily life on papyrus: inheritance and divorce trials, personal reflections, the conquest of Granada in 1492 and the earthquake that devastated Málaga shortly afterwards. Around 1500, forced to convert to Christianity or leave his homeland, he decided to do the latter. In the hope of returning, he hid three manuscripts in a wall of his house: the two books written by him and a Koran dating from the 12th or 13th century. They were never seen again until workers dislodged them while doing renovation work at a house in the village.

They remained hidden for 500 years until June 28, 2003. On the 20th anniversary of the discovery, the owner of the house, Magdalena Santiago recalls: “It was a surprise. No one expected something like this to show up,” adding that the property was almost “falling down.” Protected by straw, they were sandwiched in the hollow of a cupboard hidden in the original wide walls of the Andalusian house. Other books dating from the period have also been located after spending centuries hidden in walls in different parts of Spain, but this Koran is one of the two oldest ever discovered in the country. “It was an extraordinary find,” says María Isabel Calero, a retired Arabist who spent a long time studying the originals at the University of Málaga 20 years ago.

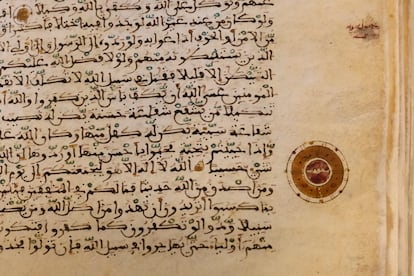

Today, after delicate restoration — with grafted paper — they are preserved in the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Málaga, managed by the regional government of Andalusia. The administration edited a facsimile of the Koran in 2009, which became a ceremonial gift together with research on the three books entitled Los manuscritos de Cútar (The Cútar Manuscripts), led by Calero. The religious text is square in shape and dates from the 13th century, the Almohad period in Spain. It is made from parchment of calf and sheep skins. Its importance can be seen in the decoration: there are lace borders, Solomon’s knots, shells and flowers in red. The calligraphy is in black and green ink, which make the text a luminous composition that has survived the passage of centuries.

There are two theories as to why it was in the hands of Al-Ŷayyār and why he took such great care to hide it after the prohibition of Muslim religious books at the beginning of the 16th century. The first theory is that it was possibly a family heirloom. A Koran passed down from father to son that each heir wants to preserve at all costs. The second is that it belonged to the mosque in Cútar — the village’s present church was built right on top of it in the 16th century — and that, in his role as imam, he decided to hide it so that it would not be destroyed. In any case, his hope was to get it back someday. “The word at the heart of this story is fear: that someone would discover the manuscript or that it would disappear,” says Calero. During her research she was even more impressed by the other two manuscripts, which were “full of curiosities” and whose last annotation is from the year 1500.

Al-Ŷayyār is their main author, but there were more because there are different handwriting styles among its pages, sewn with linen thread. One of them — now called L14029 — is made up of 111 sheets of Arabic paper and its contents are related to the work of the alfaquí, whom Calero defines as “a cultured man, with concerns, a copyist [who was] probably of urban origin.” She believes that if Al-Ŷayyār was assigned to Cútar, it was for two reasons: the surrender of Málaga to the Catholic Monarchs, and the family of his wife, Umm al-Fath, who was originally from there. In the text, cases of land distribution, marriages, inheritances, neighborhood disputes, and separations that the wise man judged are recounted in the form of individual chapters. Among them, that of ‘Ā’iša bint al-Qurṭubī, a woman who was getting divorced for the second time. There are also pages dedicated to mathematics — the multiplication table is written in full — some poems and the computation of the sunrise and sunset for the dates of Ramadan.

The second book — called L14030, on 134 sheets of Italian paper — is more personal. There are both parts that are copied from other books and sermons (“Do not commit injustice when you are powerful”), esoteric and superstitious questions. It includes poems by the imam himself. This codex also contains news that affected the author personally, such as the Christian conquest of Granada and Vélez-Málaga, and the earthquake of 1494, which destroyed “150 houses” in the capital.

All the books can be consulted digitally in one of the rooms at the exhibition center that was inaugurated in Cútar last autumn. It is open every weekend and contains many details of both the discovery of the manuscripts and their context, when the municipality was part of the taha de Comares (district of Comares), of which only five farmsteads have survived to the 21st century: the current villages of Benamargosa, Almáchar and El Borge, as well as Comares and Cútar. All near to each other, the villages are linked by winding roads that snake through a landscape dominated by mango and avocado trees and a handful of old vineyards. “The environment has changed, but the municipality has remained prctically the same as it was in the times of Al-Andalus,” says the mayor of Cútar, Francisco Ruiz.

After many disappointments, the local leader found an ally in Juan Bautista Salado, archaeologist, expert in Al-Andalus, and director of the Museum of Nerja, who took responsibility for the exhibition project. “The idea is to enhance the value of the books, but also, through the information we got from them, to explain what Andalusian society and its way of life were like,” says Salado. The specialist wonders why no one thought of protecting the walls in which the texts were found, in addition to the texts themselves. “The dwelling must have been built in the 15th century, at the very least, and now only a few original walls remain. The rest was thrown away in the renovation,” he says, although he believes that Al-Ŷayyār’s is a story of hope, of how, despite being expelled, he dreamt of returning to recover his land, his home, and his books.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Archived In

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Oona Chaplin: ‘I told James Cameron that I was living in a treehouse and starting a permaculture project with a friend’

- Sinaloa Cartel war is taking its toll on Los Chapitos

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Why the price of coffee has skyrocketed: from Brazilian plantations to specialty coffee houses

- Silver prices are going crazy: This is what’s fueling the rally