Libraries become the last refuge for Washington’s homeless

Faced with Trump’s order to remove encampments in the city and the growing presence of the National Guard, they are the only public space where people can take stay during the day without being forced out

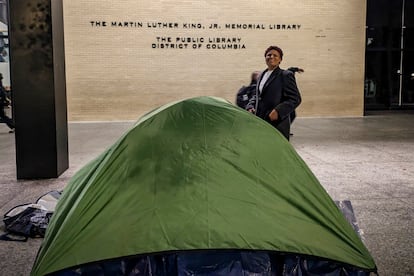

Laquisha Spencer lives in a green tent in front of the Martin Luther King Public Library, the largest in Washington, in the city center. In the afternoons, she sweeps the sidewalk at the library’s entrance and spends much of the day using its computers. She needs them for several legal cases, ranging from child custody to lawsuits she has filed against the city police and other agencies. “I use the library all the time, I go there for breakfast, and they give out blankets and, after events, they hand out food,” says the Texas native, who hopes to finish her law degree once she secures stable housing.

Her tent has already received an eviction notice, and in the coming days the Metropolitan Police will destroy it, throwing away everything inside. This has happened to her several times before. Spencer says that in the four months she has been living near this library, her tent has been taken away three times. She claims that civilians have even come to kick at her tent, while police officers have threatened her with pepper spray “just for being homeless.”

Like her, hundreds of homeless people have been evicted from their tents in parks and public spaces after U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order called “Making the District of Columbia Safe and Beautiful.” The order mandated the “prompt removal and cleanup of all homeless or vagrant encampments,” and coincided with the deployment of hundreds of National Guard members to the capital, who are often the ones in charge of the “cleanup.” In August alone, 50 encampments were destroyed in the capital, according to the White House.

Following the Wednesday shooting of two National Guard members in Washington, D.C., President Trump and the Department of Defense announced they will send an additional 500 National Guard troops to the capital. Given the legal limitations on the military’s ability to perform law enforcement duties, this deployment is expected to further tighten the crackdown on the city’s homeless population.

Rising cumulative inflation, high living and rental costs, stagnant wages, a lack of affordable housing construction, increasing unemployment, and cuts to social and food programs are some of the realities that leave many people at risk of becoming homeless. In fact, 69% of Americans live month to month without being able to save, exposed to bankruptcy from any unforeseen event. Faced with these challenges, at least 8.9 million people work two jobs just to make ends meet.

In Washington, a city of just over 702,000 inhabitants, there are 5,138 people experiencing homelessness, according to the annual report of the Metropolitan Area Council of Governments. Eighty-one percent of that population identifies as Black. However, the estimate is conservative because it does not include students, families, or people living in their cars. Many homeless people prefer using tents over going to available shelters, due to limitations such as restricted hours or space, as well as concerns over violence, theft, mental illness, or substance abuse among some shelter residents.

“A good tent insulates you from the cold, you can fill it with blankets and store your things. You live on your own schedule,” says Brian Holsten, who until recently lived in a camp in a park on Massachusetts Avenue. Now he sleeps outdoors under the roof of the Martin Luther King Library. He prefers to stay on the street rather than go to a shelter so he doesn’t have to worry “about getting there before the shelters close,” since he works late into the night at a supermarket in Fairfax, Virginia, a suburb of Washington.

Shelters in the capital vary by type, operating hours, and access restrictions. Some are for men, others for women, and some for families. Currently, there are three-day shelters that provide refuge to approximately 300 people daily. Between nonprofit organizations and the city government, there are 20 night shelters that, although open around the clock, have limited capacity due to the number of available beds. To prevent deaths from hypothermia, the city opens temporary shelters and plans to offer 1,177 beds for men and 507 for women at the peak of winter — a figure lower than last year’s.

“People are fighting over beds. I was assaulted several times in a shelter, especially by men. Many men don’t respect women, and the security guards do nothing. I prefer to stay out here,” says Laquisha, who hopes to obtain subsidized housing in the coming weeks, partly funded by the Washington mayor’s office.

Librarians as social workers

Even before the destruction of encampments ordered by Trump, libraries were shelters for the homeless, but they are playing an even more central role. “Since day shelters can only accommodate less than 5% of the homeless population, libraries become the only indoor public space they can access without being evicted during the day,” explains Francesca Emanuele, a doctoral candidate in anthropology at American University and an urban researcher.

At the city’s 26 public libraries, people experiencing homelessness can use computers to apply for jobs, communicate, find entertainment, access training, and find resources to address homelessness. In fact, the library system offers a program called We Care that provides emotional support, housing referrals, assistance with obtaining identification documents, and clothing donations, among other services.

The homeless community’s growing reliance on libraries has led librarians to expand their roles, with many taking on social work tasks to better serve this population, explains researcher Emanuele. “The government treats them as if they were social service personnel, trying to hide the city’s structural problems and distortions, such as high rental costs, the limited number of public housing units, and inflation, among others.”

Several librarians anonymously told Emanuele that “there are so many fights, drug overdoses, and unusual behavior in libraries” that they need to call on the DC Library Police to handle these situations. “There are more and more opioid overdoses on the premises, and we’ve received invitations to be trained in the use of Narcan,” one librarian shared, referring to the medication that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. “I don’t see any problem with being trained, but I’m not sure if I want the library to become a safe place for drug use.”

Equipping libraries with overdose medication has been attempted elsewhere in the United States. In October, a New York City borough passed a law requiring public libraries to have naloxone [the generic name for Narcan] rescue kits mounted on the walls. “Libraries are more than book repositories — they’re community centers, classrooms, senior hubs, youth spaces, workforce training sites, and now, lifesaving access points,” said State Senator Steve Rhoads, who signed the legislation into law.

“We’ve been implementing what they have in New York for some time now. In fact, our Health Department has been providing Narcan for a while. Also, through the library, we have specialists who work specifically with homeless people,” says Reginald Black, who as a homeless person frequently visited libraries and now works as a housing liaison for the nonprofit organization Serve Your City/Ward 6 Mutual Aid, which connects homeless Washington residents with support and services.

The Washington, D.C. Department of Human Services maintains that a peer mentoring program operates in the city’s public libraries. Certified professionals, trained by the Department of Mental Health, connect homeless individuals and other citizens with services offered by the district.

For Emanuele, the new roles librarians are taking on are side effects and symptoms of a structural economic problem that, if not addressed by offering a decent housing option, will continue to push more people onto the streets and condemn the few public spaces and libraries to be the daytime refuge for those who are becoming homeless.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.