Small Tennessee town observes 100 years of the ‘Scopes monkey trial’ that condemned the teaching of evolution

A young biology professor was prosecuted in Dayton in 1925 for teaching Darwin’s theory, a conflict that continues a century later. The trial was the first to be broadcast live on the radio

One hundred years ago, in rural America, a trial took place that would deserve a movie, if it weren’t for the fact that the movie has already been made: in 1960, Stanley Kramer directed Inherit the Wind, based on the play of the same name by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, which fictionalized the famous trial in which John Scopes, a young high school biology teacher, was prosecuted for teaching Darwinian evolution. The “Scopes Monkey Trial,” as it became known, was a milestone in the eternal battle of rational scientific thought versus belief-based denialism, a conflict that continues to rage a century later.

The story begins on a Sunday in 1921 with a sermon at the Baptist Church in Dayton, Tennessee. A preacher recounts how a woman lost her faith after attending a college course on evolution. Among the parishioners is a farmer named John Washington Butler, who is not content with being scandalized like the others; terrified that one of his children might follow in that woman’s footsteps, he runs for a seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives the following year with a campaign promise: Darwin’s theory will not be taught in any public school.

No sooner said than done: Butler drafted the legislation on the morning of his 49th birthday, after breakfast, sitting in front of the fireplace. The Butler Act forbade public school teachers “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Fines for violators were set at up to $500 — about $9,000 in today’s dollars.

The bill passed the House by an overwhelming majority of 71 to five. Before passing through the Senate, the debate spilled into the streets, but that didn’t stop the bill from being ratified and signed into law by Governor Austin Peay on March 21, 1925.

A political give and take

It wasn’t just religious convictions that drove the Butler Act; some representatives simply preferred not to upset their own constituents. As for Peay, considered a progressive Christian, he had his own reasons. According to science historian Adam Shapiro of Birkbeck University in London and author of the 2013 book Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools, compulsory schooling was expanding in the U.S. at the time. For Peay, the law was “partly a political compromise,” Shapiro says. “Accepting it allowed the governor to push through progressive laws to build more schools and train more teachers” without raising eyebrows in religious communities.

In any case, Peay hoped the new law would go unnoticed, given that Darwinism had already been around for half a century and was already extremely popular. But he was wrong: Tennessee’s ban prompted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to publicly offer to defend any teacher who got sued, in a bid to prove the law unconstitutional in court.

News of the ACLU’s announcement reached back to Dayton, where an engineer named George Rappleyea accepted evolution and opposed the law. He saw the resulting commotion as an opportunity to put the small town in the spotlight, which would attract a large audience and help revitalize the precarious local economy.

Rappleyea was the architect of Scopes’s trial: not only did he convince local authorities to mount a case, but he also chose the defendant, since no one had yet been charged. He summoned Scopes, 24, who wasn’t even a biology teacher but a football coach covering for an absent instructor, and asked him if he had ever taught evolution. The young man wasn’t even sure that he had, but he was sure that the class textbook discussed it — a book he hadn’t picked out himself, but rather the state of Tennessee. Scopes accepted the role of defendant and even encouraged his students to testify against him, which they did.

The first nationally broadcast trial

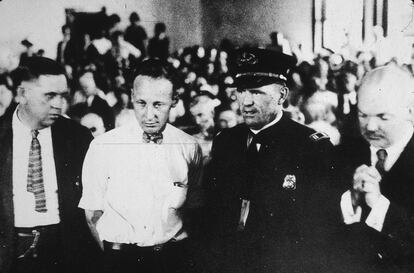

The trial, the first to be broadcast nationally live on radio, took place from July 10 to 21, 1925. As Rappleyea had planned, Dayton became a grand carnival, complete with circus monkeys. Kramer’s movie immortalized the dialectical clashes between two charismatic characters, who in the work of fiction appear under assumed names. The agnostic lawyer and ACLU member Clarence Darrow was hired for the defense, and former Democratic presidential candidate and former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan took charge of the prosecution. Bryan was a fundamentalist Presbyterian who had led a crusade against the teaching of evolution in several states.

Darrow enlisted expert testimony from scientists and even called Bryan himself as a witness, putting him on the spot by highlighting the absurdity of a literal interpretation of the Bible. But none of this was of any use; for Judge John Raulston, the only relevant issue was whether Scopes had broken the law. The jury found that he had, and the teacher was fined $100, a verdict that was later overturned on a technicality.

“After Scopes, no one was prosecuted again for violating Tennessee law,” Shapiro notes. In 1955, Inherit the Wind debuted on Broadway, reigniting the controversy over a law that was still on the books. When the ACLU petitioned for its repeal, the Tennessee government responded that the law was effectively dead, but that there was no interest in starting a political fight to overturn it. It wasn’t until 1967, when another teacher named Gary Scott filed a lawsuit against the Butler Act after being fired for violating it, that the Tennessee Assembly took the opportunity to vote on its repeal, which the governor signed on May 18.

But the Tennessee case, while the most high-profile one, was not the only one. The following year, in 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a similar law in Arkansas was unconstitutional. However, according to Shapiro, even in states without specific laws, “often not teaching evolution was simply the norm.” The historian explains that in most schools, avoiding controversy was paramount. “Then as now,” he adds.

Anti-evolution changes its name

“Anti-evolution strategies have shifted in response to legal cases,” Shapiro continues. So-called Creation Science managed to circumvent obstacles by claiming to be based on observations of nature until it was declared unconstitutional in the 1980s; only to be replaced by Intelligent Design, “which argues against the sufficiency of evolution to explain life and doesn’t specify any theological suggestion as to who or what the designer is,” Shapiro explains. In 2005, a new court case also struck down the teaching of this version; but, Shapiro says, academic freedom laws still protect educators who can teach whatever they see fit without restriction.

On the occasion of the centennial of the Scopes trial, Glenn Branch, director of the National Center for Science Education, writes in Scientific American that “teaching evolution has a bright future in the U.S.” Branch cites surveys according to which in 2007 a bare majority of high school biology teachers reported that they emphasized the scientific credibility of evolution while not emphasizing creationism as a scientifically credible alternative, but by 2019 this figure had grown to “a commanding majority” of 67%. Will this trend be consolidated under Donald Trump’s second term?

Evidence of a lingering resistance is that in 2017, the placement of a statue of Clarence Darrow in Dayton — another statue honoring William Jennings Bryan was erected in 2005 — sparked opposition from part of the community. A local resident told The New York Times that such an “atheist statue” could unleash a plague or a curse. Even today, in conservative rural America, evolution proceeds slowly.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.