Life’s revolution: From the selfish gene to the collaborative cell

Just as a living being has tissues and organs, society has structures that provide it with resilience and allow it to adapt to changes and evolve

We can view society as an organism composed of individuals who, through their ideas, activities, and above all, interactions, keep it functioning. Just as a living system has tissues and organs, society has structures that provide it with resilience and allow it to adapt to changes and evolve. In the 1970s, the book Sociobiology extended concepts from genetics and evolutionary biology to human behavior and, along with Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene, proposed a view of human nature as an inevitable consequence of our genes and their history. The central argument in this idea is that organisms are nothing more than products of genes whose ambition is to propagate themselves endlessly over time, leading them to compete with one another. In this world, a lion and an antelope are merely vessels that the genes of each animal construct to propagate themselves: the lion kills the antelope because the genes it carries seek to propagate themselves at the expense of the antelope’s. The organism has no value beyond being a fleeting product of the genes for their survival. In these battles, genes mutate, altering the designs of their vessels to improve their reproduction. Darwin had already said that life on Earth was stained with blood in the teeth and claws of animals. Dawkins adds the notion of selfishness to the elements of inheritance in the battle for survival.

The central role of genes in our existence is evident today in the constant references to the idea that who we are, our health, disease, and even our longevity, can all be reduced to our genes. Sometimes, this argument extends to our collective actions. When Margaret Thatcher said that there is no such thing as society, only individuals, she pointed to competitiveness and selfishness as the foundations of social success. Today, this rhetoric hides behind racism, discrimination, and inequality. It is no coincidence that Trump and Musk speak of good and bad genes to justify their immigration and fertility policies. It is interesting how genetics is a double-edged sword that sometimes requires argumentative contortions to free the gene-centric view of life from its social consequences. But perhaps sidestepping these problems does not require dialectical subtleties but rather putting genes in their proper place. To do this, we must recognize a biological reality that is right before our eyes and that provides a more optimistic and liberating vision of life. A vision centered on an element of our biological essence with more power and better skills than genes: cells.

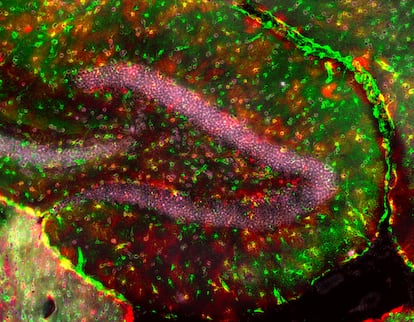

Organisms are the creation of cells. Each of us is a collection of a trillion cells that coexist and work alongside the same number of bacteria, which, by the way, are also cells. And in this reality, there is something even more astonishing. Because nothing lasts forever, while you are reading this, your body is in a state of flux, continuously renewing itself from the wear and tear caused by age or interactions with the environment. Every second, your bone marrow produces two million new red blood cells (yes, you read that right: two million), your skin cells are in a process of total renewal that will culminate by the end of the month, and your intestinal cells, bombarded by your last meal, will do the same within a week. And all of this happens in a cooperative environment among different tissues: the blood distributes fuel to make it all happen, the skin protects the delicate machinery that keeps us alive, and the intestine creates fuel from food. The cells of the heart, brain, and eyes are more stable, but they depend on the others. An organism is a society of cells in constant renewal, where each one does its job with the goal of keeping the whole functioning.

Cells are complex and marvelous structures invented over the course of evolution, the true origin of life as we know it. The diversity of animals and plants we enjoy is not due to the catalogs of genes of each organism but to the variety and organization of the cells that build us and what they do with the genes. If there is any doubt about the creative power of the cell, we need only look at the process by which the union of an egg and a sperm transforms itself into an organism through the crucible that is the embryo, from which emerges the trillion-cell structure that shapes us. Contrary to what is often said, genes do not have a blueprint for an organism. But even if they did, who would execute it? The protagonists of the process that is the creation of an embryo are the cells, which multiply, diversify structurally and functionally, and, communicating with each other and their environment, build tissues and organs. Cells know how to count, they create and shape space, placing each part of the body in its proper place and endowing it with the global functionality required for the organism’s survival. In these processes, genes are not the protagonists but rather a barcode for the tools that cells use in their tasks. Genes ‘do’ what cells need, when and where they decide. It is cells, not genes, that have woven our being in our mothers’ wombs and that allow you to read these lines, listen to music, talk with friends, and dream.

It is true that our knowledge of the cell is still primitive, but we must not let the current obsession with genes obscure their limitations or inhibit us from exploring the vast amount we still do not know about cells.

The view of biology from the perspective of the cell contrasts with that of the gene. Where the gene is selfish, the cell cooperates for the common good, which, in the end, is the organism. When a cell, imitating the selfish gene, rebels and seeks to impose its own interests, the result is disease, with cancer as the prime example; the consequence is the destruction of the organism.

Seeing cells as the architects of life promises a new vision of biology. But perhaps we should also see them as a reflection of the society we aspire to, as an example of what can be achieved when the goal is not competition for a fleeting future but the result of collaboration among diverse elements—cells, individuals—for a common good. Biology is not here to provide scientific justifications for social actions, but perhaps in these days of uncertainty, we can look to biology for hope and inspiration. Just as an organism is not a collection of selfish genes but the result of the cooperative work of its altruistic cells, a society is not a collection of individuals seeking their own good at the expense of the most vulnerable but, like an organism, the result of cooperation among its individuals, each contributing the best they have to provide resilience, justice, and a future in the form of the common good.

Alfonso Martinez Arias is an ICREA Research Professor at the School of Medicine and Life Sciences of Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. His book “The Master Builder’ (Basic Books) was published this week in Spanish as “Las arquitectas de la vida” (Paidos).

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.