The migrants targeted by Trump: From the waiter serving morning coffee to a newspaper cartoonist

The U.S. president’s plans for mass deportations have a direct impact on individuals like Miguel Hernández, a Mexican worker in New York, and Iván Almonte, who has lived in the country for decades without legal documentation

Anyone — including Donald Trump — can find Miguel Hernández at Georgina Diner in Queens, New York, from Monday to Friday, where he has been working as a waiter for several years. He’s there on Tuesdays, smiling and dressed neatly in his work uniform. People have advised him to be cautious these days, with talk of massive raids and the possible and unexpected arrival of agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), but Hernández has no choice but to continue with his work. If he doesn’t work, he doesn’t eat.

“Neither the cold, nor the snow, nor the president can stop us. We left with God’s blessing and we returned with God’s blessing,” says the 44-year-old Mexican, who left his hometown in Oaxaca at the age of 13, crossed the border, and has lived in the United States without legal status ever since. Hernández spoke these words the day after Trump, on his first day as president, declared a “national emergency” at the southern border and announced the deportation of “millions and millions of criminal aliens.”

A few years ago, Hernández married his wife, the mother of his two children, in an effort to regularize his immigration status, but so far, he hasn’t been successful. In 2010, he crossed the border to visit his mother in Mexico, who was ill with cancer. Upon his return, U.S. officials stopped him three times while trying to re-enter. His case, he explains, is still in the courts. “We don’t know what will happen now with Donald Trump’s new laws. I’m afraid, like all migrants, I’m afraid of being separated from my family, from my children.”

But that fear doesn’t stop him. Hernández is a member of the Raza Zapoteca organization, which advises the community on what to do if an ICE representative knocks on their door or approaches them on the street. They have distributed audio messages in the Zapotec language through various channels, offering advice not to open the door, ask for orders signed by a judge, avoid answering any questions or signing documents, and request the presence of a lawyer.

The organization has also set up a hotline, with the help of the Mexican Consulate in New York, to report arrests in the community. “They want to instill fear, and it’s not fair. The community needs to live its life,” insists the waiter.

Why do I have to hide?

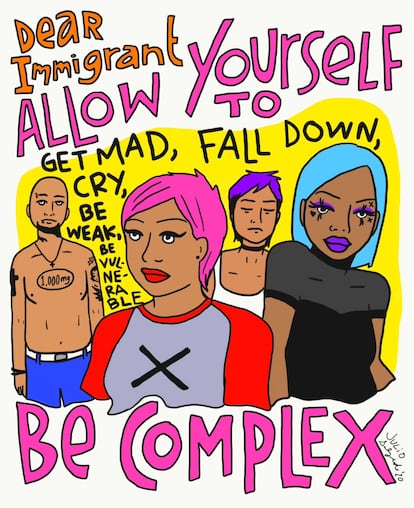

Hernández is not the only one who refuses to hide, and more and more are choosing not to. “We are here, we are doing things the right way, and we are trying to get ahead. Why would I want to hide from my situation? I’m not ashamed of being married to someone who is undocumented,” explains Isela Izaguirre, a U.S. citizen married to a Mexican immigrant who has already been deported twice.

Izaguirre lives in Houston, Texas, and has already exhausted all avenues to regularize her husband’s immigration status. Four years ago, her husband applied for a U visa, which allows undocumented immigrants who have been victims of crimes to stay in the country, but the process has not progressed. Recently, they applied for the parole-in-place measure, introduced by the Joe Biden administration to grant legal status to undocumented immigrants married to U.S. citizens, but they have not been successful either. “We are always afraid that he will be arrested and deported again. Trump wants to deport too many people.”

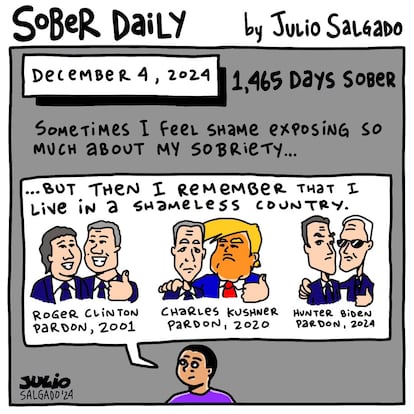

Like the warning of a natural disaster, Julio Salgado has learned to live with uncertainty. “Just as we prepare for an earthquake or a fire, we have to prepare for deportations. But we must not let that fill our lives, because it can make us sick.” Salgado is a Dreamer who has lived under the threat of deportation in the United States since he was 11 years old and is now 41. Three decades of uncertainty have become his normal.

For now, he is protected by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), an immigration policy from the Barack Obama era that allows some undocumented immigrants to receive work permits and delay their expulsion from the country. But with Donald Trump in power, that could change: “The fear of deportation is real, but as a community, we are also preparing, educating ourselves about what our rights are.”

Salgado is a multimedia artist and the author of the comic Good Immigrant, Bad Immigrant, published by the Los Angeles Times. He was born in Ensenada, Mexico, and grew up in Long Beach, a coastal city southeast of Los Angeles. He frequently travels around the country to talk about his work, and on Tuesday, he flew to Chicago, where Trump has warned that detentions of immigrants without permanent legal status will begin.

“Julio, I heard that they are going to start doing raids in Chicago. Are you sure you are going to go?” his mother asked him on Monday. His answer is the same as always: “We are going to be fine, Mom.”

Since Donald Trump launched his campaign for re-election, undocumented immigrants and activists across the country have been preparing to confront the tightening of immigration policies he enacted during his first term — on the streets and in the courts. In truth, immigrants begin preparing the moment they set foot in a country that relies on them for labor but refuses to grant them citizenship.

While Trump attended his inauguration ball on Monday, Iván Almonte was participating in a virtual forum with a network of North Carolina organizations, sharing resources with families on what to do if immigration agents knock on their door or stop them on the street. “People have to be aware that their tactics are designed to hunt people down[...] We are all exposed. We know that agents are aggressive in their approach, and because you’re Hispanic or speak Spanish, you are already a target,” explains Almonte, who coordinates a rapid response group to raids in Durham, North Carolina.

Almonte, 45, is Mexican and has been living in the United States without documentation for decades. During the forum, as Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance celebrated with cheering supporters, others in the chat shared their fears of running into immigration officers. “What do we do if we have to go to court? Should we show up?” writes Janny, who has an open case in immigration court. Irma has a similar worry: “Should we send our children to school or not? They want to go to school, but that’s the fear.”

Almonte is Mexican, 45 years old, and has been living in the United States without documents for decades. In the forum chat, at the same time that Trump and Vice President J. D. Vance dance in a stadium full of cheering supporters, some share their fears of running into an immigration agent. “What do you do if you have to go to court? Should we show up?” writes Janny, who has an open case in the immigration courts. Irma also has a doubt: “Should we send our children to school or not? [Immigration officers] want to enter schools, that’s the fear.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.