Does anyone care about the death of Victorio Hilario, the delivery worker killed on a corner in New York City?

In 2020, he was run over by a man in a car who sped off. His family has spent years fighting to get the perpetrator convicted. Meanwhile, Hilario has become a symbol for 65,000 app-based delivery workers in New York City, as they try to improve their working conditions

Outside courtroom No. 600 of the Bronx County Hall of Justice, Elías Hilario — who is wearing a plaid shirt, jeans and a jacket — looks tired of waiting for the judge. The hearing was scheduled for the early hours of the morning, but it’s already almost 3 p.m. on a cold and sunny day in mid-March. After so much waiting, it seems that justice will never come.

When the guards finally allow entry into room 600, the judge — with a serene face — waits under a sign that says “In God We Trust.” The first bench on the left is occupied by Yeramil Alvarez, a 24-year-old young man of Puerto Rican descent. Four years ago, he drove his 2020 Black Genesis sedan over a food delivery man on a corner of the popular Grand Concourse, a 5.2-mile-long thoroughfare that runs through the Bronx. The avenue is home to numerous local businesses, residential buildings, the Bronx Museum of the Arts and the former home of Edgar Allan Poe.

Yeramil is handcuffed. He very rarely looks up, only to acknowledge the judge. He never looks around. On the day of his sentencing, he’s accompanied by his lawyer and three other people. The benches on the right are filled with those who are accompanying Elías, including employees of Doordash, Uber and Relay; activists; friends and family members from Mexico. They’re all waiting for the judge’s final word, four years after the driver on trial ran over Victorio Hilario, Elías’ brother. A Mexican national and a food deliveryman, he was one of the thousands of people who — during the Covid-19 pandemic — were deemed “essential workers” by politicians and government officials. However, in the long-run, it’s clear that the lives of these individuals didn’t mean much to them at all.

Elías — who doesn’t speak English — offers a statement with the help of an interpreter, who facilitates communication between him and the judge, who doesn’t speak Spanish. He’s been waiting for this moment for a long time, ever since he called up his brother to make plans: they were going to have tacos dorados for dinner. But they never got a chance to eat together.

Elías has been waiting for justice ever since the culprit fled the scene of the crime. Two years ago, the police informed him that the suspect was arrested. And then, he was made aware that the guilty party had paid bail and was free again. Since then, many other food delivery workers in New York City have died, while carrying orders from McDonald’s, Domino’s, or Papa Johns. None of them have received justice.

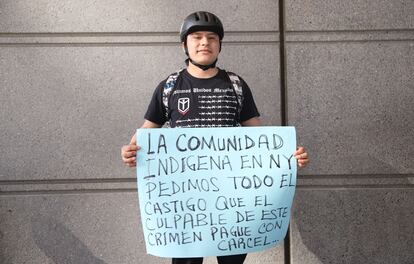

The life and death of Victorio Hilario — who was killed at the young age of 37 — exposes the map of vulnerabilities that many migrants face in New York when they work in the food delivery sector. Currently, some 65,000 app-based delivery workers are exposed to the dangers of the streets, or to the weak labor protections offered by large corporations. It was amidst the outrage over Hilario’s death that many food delivery workers in the city began to organize and demand proper benefits for their community.

Elías was the first of the brothers to leave San Juan de las Nieves. It’s a Mexican town so small that almost everyone is family. While there are no movie theatres or doctors, there’s abundant land for the cultivation of corn and lime blossoms, which the local farmers grow in rows of endless yellow dots.

After seven days spent crossing the desert and the U.S.-Mexico border, he arrived in New York City. The year was 2002. The skyscrapers and trees caught his attention.

“I asked a cousin why the trees were so dry,” he recalls. “He told me that, by the time summer began, they would quickly be sprouting.”

That same year, Selso — another of his 12 brothers — arrived in the Big Apple. Victorio was the next to show up. He was 22-years-old: he started working at a bar in Manhattan, collecting dirty glasses and dishes. He then worked stocking the fridges at a deli in Kingsbridge, in the northwest portion of the Bronx. He also made sandwiches at another deli on the Lower East Side, until a new owner came along, with new rules. Victorio soon became unemployed. As did Elías.

The year 2019 was almost over. In just a few months — when the city became the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic — thousands of New York restaurants would close their doors. Faced with the attractive payments offered by food delivery app companies at the time (some delivery drivers claim that they earned between $200 and $300 per day during the pandemic) and without many other options, the brothers became essential workers, thus joining the 2.5 million people on the frontlines during the lockdown in the city.

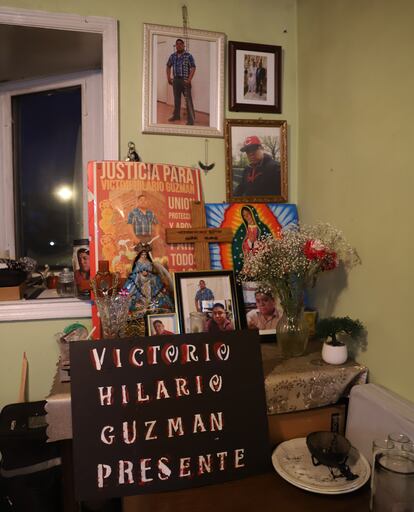

In the apartment in the Fordham Manor neighborhood — where the brothers have lived together since 2005 — several helmets, fluorescent vests and bicycles are piled up. In one corner, the thermal bag that belonged to Victorio remains intact. Inside, there’s a wallet that holds $75 in bills and $3.25 in coins. On December 23, 2022 — the day of the accident — Victorio went to the ATM, withdrew $100 and spent $25. “That’s his money,” Elías tells EL PAÍS. “It’s money that he worked for. We don’t touch it.”

The thermal bag contains the receipt for a package of five pairs of shoes worth $52.91 that Victorio sent to his family in Tlapa, in the Mexican state of Guerrero. His Metrocard, a torn belt, tennis shoes, a red cap and blood-stained clothing also remain inside. “For us, that bag is demanding justice,” Elías says quietly.

Victorio went to work in the mornings, while Elías took afternoon shifts. Victorio was moderate and cautious. Elías has a more reckless nature. If Victorio made about 20 deliveries a day on his Harrow bicycle, Elías sometimes made up to 40. “My brother told me: ‘I’m not going to kill myself for two or three more dollars, so don’t kill yourself working,’” he remembers. Victorio never had an accident, but Elías did, when a car hit him while he was working, throwing him a few feet on Ninth Avenue. “He rode very carefully,” Elías says. “I like to race, but he was calmer, he did things carefully.”

On one occasion, Doordash — the home delivery giant that has 37 million users, more than one million delivery people, reported revenues of $8.63 billion in 2023 and leads the market in New York — blocked Victorio from the app. The delivery man arrived at a woman’s apartment building to deliver a food order and the woman asked him to come up. Victorio couldn’t open the front door. “There, he waited and waited. The lady came down with a lot of anger and started insulting him,” his brother explains. “He delivered the food and, shortly afterwards, she reported him, she said that he had arrived drunk and drugged… the lady invented everything. When he wanted to work the next day, he was already blocked.”

On the morning of the day of the accident, Elías asked his brother to pick up three sodas, three packages of tortillas, cheese, sour cream and lettuce. For dinner, they would eat some tacos dorados. Around 7 p.m., however, the Doordash app rang. Victorio washed up in the bathroom and left on his bike. He was so fast that Elías didn’t have time to say goodbye to him.

Around 8 p.m., he called Victorio to have dinner together.

“He didn’t answer me anymore… the call went through and he didn’t answer me. I was sad that he wasn’t going to come back. I thought he was working.”

Around 10 p.m., two people in suits and ties rang the apartment’s doorbell. Elijah thought they were religious preachers. Then, they knocked harder on the door. At that point, Elías thought they were immigration officials. “And, as they say, if [ICE] or detectives knock on the door, don’t open it.” When he finally did open the door, they told him that his brother, Victorio, was seriously injured. He was being treated at St. Barnabas Hospital.

“He was in a coma. His heart was beating, but the specialists told me that he was in a critical situation. I went to see him and started talking to him. I told him ‘I’m with you, why did you go out to work yesterday? We agreed that we would have dinner together.’ Then, tears started to fall [down his face]… he was listening to me.”

Victorio Hilario died three days later, at four in the afternoon in the Bronx. It was 3 p.m. in San Juan de Las Nieves.

“I remember my son as a hero, who went around distributing food for people who couldn’t go out during the time of the pandemic,” says his mother, Zenaida Guzmán Barragán, 78, from Mexico. “Always happy, friendly and with the desire for self-improvement.”

***

In courtroom No. 600, Elías — with the microphone in his hand — speaks to the man who hit his brother. His voice is shaking. “You have left a deep wound, damage that you will never be able to repair,” he says, in front of the judge. Yeramil remains still. “I’m sure that humane justice is being too kind to you.”

Victorio Hilario is one of the many food delivery workers who have died in recent years in New York City, under the intense pressure to deliver more and more food to people’s homes and earn better income. One group made up of delivery people on Facebook — El Diario de los Delivery Boys en la Gran Manzan (translated as “The diary of delivery boys in the Big Apple”) — has recorded more than 40 cases of accidental deaths in the city since the end of 2020.

Alejandro Santos Escamilla, 33, also died after being run over while working on December 23, 2022. His family in Mexico never learned the details of the case, not even the name of the person responsible for his death. “Some friends told us that he had an accident,” says his niece — Ely Santos — from Tenango de las Flores, Mexico. “We know practically nothing. We never knew what he was like, or who he was, or where [he lived]. He left here when he was 15-years-old… we only saw him again when he arrived in his coffin.”

Ligia Guallpa — director of the Worker’s Justice Project, an organization that has been working for the labor rights of migrants in New York for more than a decade — assures EL PAÍS that many of these workplace accidents are due to the fact that “the worker feels that he [or she] has to work 12 hours a day and race as fast as possible to make the next delivery, because at the end of the day, their salary depends on tips.”

After facing many lawsuits, New York City finally approved a legislative package that raised the minimum wage for food delivery workers and compelled large companies to pay $17.96 per hour. Previously, they paid only $7 per hour. This law — among other legislative gains — aims to make the work done by delivery people “safer.”

However, a law that’s a benefit for some delivery workers has now also become a nightmare for others, as well as a proxy war. Próspero Martínez — a Mexican delivery driver who works for Doordash and Uber Eats — feels that this law isn’t only “an injustice,” but that it “becomes punitive.” Companies operating in New York City now require identification from delivery workers, who are mostly undocumented migrants from Latin America, according to a report co-published by the Worker’s Justice Project and The Worker Institute at Cornell University. Firms also offer them fewer work hours, are more selective and have eliminated tips for delivery people.

“There’s no longer certainty about how much you’re going to earn,” Martínez says. “Before March 4, delivery workers could earn between $500 to $1,000 a week. After this date, only some groups can have a good salary… it leaves a large majority without work.”

Guallpa explains that, indeed, after the law was passed, companies retaliated in a way that directly affected workers. “This fight isn’t against the workers… it’s against the multibillion-dollar companies that continue to treat workers as disposable and cheap labor,” she affirms. “By eliminating the tips that were initially received, these companies are trying to reduce the operating cost of labor. And they’re finding ways to not have to pay the workers.”

Companies such as DoorDash and Uber have publicly taken a stand against the minimum wage law, claiming that workers will be the most affected. “The city continues to lie to workers and the public,” Uber spokesman Josh Gold said in a statement to The New York Times. “This law will put thousands of New Yorkers out of work and force remaining couriers to compete against each other to deliver orders faster.”

****

Food delivery people not only expose themselves to the danger of accidents, but also to thieves who often steal their motorbikes, for which they pay almost $2,000. Among the most notable cases reported in the press is that of Francisco Villalba, 32, who died after being shot several times for refusing to hand over his electric bicycle on the night of March 29, 2021. Many of these deaths go unpunished, due to the fear of deportation felt by immigrants should they report crimes or become involved in judicial processes. This is according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Elías didn’t want his brother’s death to go unpunished, even though it took four years for justice to be done. According to the police accident report, Yeramil Alvarez accelerated his 2020 Black Genesis sedan at the corner of East 180th Street and Grand Concourse when Victorio was crossing from west to east. Victorio had picked up an order from a Popeyes restaurant: he would have earned $4 for completing the delivery.

Elías knows this route perfectly. On Grand Concourse Street — where there’s now a white bicycle in memory of Victorio Hilario — Elías can indicate, in detail, how his brother crossed the street, which route he took… even the exact point where his body fell. It left a bloodstain so large that even the rain that fell the next day couldn’t erase it.

After the accident, Álvarez fled. When he was arrested in Manhattan two years later, it wasn’t for Victorio’s death, but for driving with a suspended license. The police realized that he was the same person. He posted a bail of $75,000 and was released.

When the judge gives him the floor to speak, the young man refuses to make a statement.

In room No. 600, the judge thanks the delivery workers for “having served the community during the pandemic.” He then hands down a sentence of between one and three years in prison for Álvarez, in addition to a one-year-long ban on driving in New York after he’s released.

Elías thinks the sentence is insufficient, but he no longer feels the anger that he felt just a few years ago. He’s at peace. The person responsible for the death of his brother will serve jail time. Rubén Hilario — the younger brother of Elías and Victorio — appears overwhelmed after the trial. But he tells EL PAÍS that he’s not overwhelmed: he’s simply feeling sad.

“Before, we always waited for each other to have dinner together. Now, we feel like there’s always someone missing at the table,” he laments. “I wish it had been a fair sentence. It’s not what we expected.”

The judge knows that the Hilario family finds the sentence to be too short. He even acknowledges this. “I don’t think that the punishment I’m going to give Mr. Álvarez is going to repair the loss in the family,” he says, directing his words to those present in the room. “New York’s criminal justice system doesn’t have the ability to do that.”

On the last day in the Bronx hospital — when Victorio Hilario had been declared brain dead and his heart was shutting down by the second — his brothers made a video call so that his parents could say goodbye from Mexico. His father asked his son to forgive him. “I couldn’t give you what you needed, because we’re poor,” Félix Hilario Cruz, 82, told him. “If I had had what you needed, you wouldn’t have left. And you would be here with me.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.