The last days of death row in California: ‘We are not allowed to be human here’

The state government has been transferring the death row population in the infamous San Quentin prison to dozens of penitentiaries across California. EL PAÍS visited Kevin Cooper, who has been awaiting execution for 39 years for a crime he maintains he didn’t commit

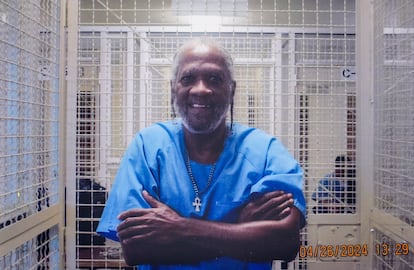

One day, in May of 1985, Kevin Cooper first set foot on death row at San Quentin State Prison, in the San Francisco Bay. Three weeks ago — 39 years later — he left one of the oldest, most famous and most feared prisons in the United States. He was heading to his new home: California Health Care Facility, Stockton (CHCF). While it has the name of a hospital, it’s actually a penitentiary.

His death sentence still weighs on him, but the change, he admits, “has been like going from hell to some sort of heaven.” Cooper is no longer required to be handcuffed and escorted whenever he’s outside the cell in which he’s serving time for a crime he maintains he didn’t commit. He has double the square footage that he had in San Quentin, as well as a window through which he can see the sky. Even his blood pressure has gone down. But the best thing, he tells EL PAÍS — in a phone call that, every so often, is interrupted by an automated voice that warns that the conversation is being recorded — is that, in the new prison, he has access to ice.

Cooper is one of 636 people on death row in California, 20 of whom are women. Of the 27 states with capital punishment, California has the largest population in the country. And not so much because California is the most populated state: rather, it’s because judges continue to sentence people to death, but they’re not killed. The last execution took place in 2006. In fact, after the U.S. Supreme Court reintroduced capital punishment in 1976, only 13 people have been executed in California.

Logic would dictate that a blue state like this should have already abolished the death penalty. However, when the issue was put forth on the ballot in 2016, 53.15% of Californians voted against repealing capital punishment. On the same ballot, another initiative was approved: Proposition 66, which was drafted to reduce prison costs and speed up the appeals system for those who await their fate for decades. It will also require the condemned work and pay restitution to the victim’s families. In 2023, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom — perhaps his party’s next candidate for the White House— announced that he would dismantle the death row in San Quentin, and that its population would be distributed to other prisons throughout California, as long as they have a lethal-electric fence.

The program began in 2020, with about 100 incarcerated people who transferred voluntarily. Four months ago, the transfer of the rest began. The process is now about to conclude. As of June 7, there were still 38 men at San Quentin, according to “the inmate locator” presumably in the hospital. The next phase of the plan involves converting San Quentin — an institution made famous in pop culture because Johnny Cash once played there (and because it was home to murderer Charles Manson) — into a “Nordic-inspired” rehabilitation center.

Many death row inhabitants suggested three preferred destinations, which the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) could take into account based on a points system, involving factors such as behavior. Cooper was granted his wish to go to Stockton: it’s about 85 miles from San Francisco, meaning that it will deter some of his visitors from going there as frequently. But it could have been worse: they could have sent him to the southern tip of California.

His preference for Stockton — which is something like a medicalized prison — is explained by his back problems, after so many years of playing basketball in the prison yard. He also has arthritis in his right knee, which he hopes will be treated at the new facility.

A month before his transfer, Cooper received EL PAÍS on death row. Outside, a radiant April sun bathed one of the most beautiful enclaves in the San Francisco Bay. “Welcome to the infamous San Quentin Prison,” he said. “In here, we’re not allowed to be human; we’re victims of a modern-day lynching.”

The prison’s visiting area is divided into a dozen barred cages, giving the place the feel of a factory farm. At the entrance, there are a handful of vending machines that only accept quarters and dollar bills, as well as a microwave in which visitors heat up newly-purchased dishes for their loved ones. The day that EL PAÍS came by, the place was full. All the visitors were women. A mother said that she’d been going every week to see her son for the past 29 years. There were also activists, wives and partners, including a woman who had traveled from Europe.

The uncertainty about these transfers — regarding both location and timing — caused anxiety to spread on death row. Many balked at the prospect of changing years of routines (even if terrible), some were concerned about being celled with someone else after decades of being single celled, while others hoped that the change might be for the better. In late April, a man was found dead in his San Quentin cell shortly before his transfer. Apparently, he committed suicide.

On the morning of the visit by EL PAÍS, the man who has been on death row in California the longest — a 66-year-old Native American named Douglas “Chief” Stankewitz — summed up the paradox. He said through the bars of his cage, while chatting with his friend Colleen Hicks: “I’m worried about how the other inmates are going to receive us. What have they told them about us? I’m also worried about how the administration will behave… Their ability to punish us knows no limits,” he sighed, during his conversation with EL PAÍS.

“On the other hand, I’m excited,” Stankewitz shrugged. “They’ve told me that I’ll be able to pet dogs and [maybe] learn computer science.”

He has spent the past 46 years behind bars for the murder of a woman. His sentence was commuted in 2019 from the death penalty to life imprisonment — without the possibility of parole — in light of the irregularities that plagued his two trials. He’s currently waiting for a judge to decide on a habeas corpus petition, which could allow for his release.

Alexandra Cock, of his legal team, expressed in a telephone conversation the hope that this will be the case, although with a caution shared by those who have been working on cases like that for a long time: it is better not to trust too much to avoid another disappointment. “The judge made it difficult for us to present our case for wrongful conviction for years,” Cock said, “but recently, I think his attitude has changed. And honestly, I find it hard to believe that he doesn’t agree with us. The arguments we have presented are very powerful. And the evidence points to his exoneration.”

Keith Doolin is another person recently transferred. He’s been on death row for 28 of his 51 years — “illegally imprisoned,” he interjected — convicted of killing two sex workers in Fresno after receiving ineffectual counsel from his appointed trial lawyer. What worried him most about the move was that he would lose his most precious asset — a typewriter — which he uses to work on his case. He was also worried that he would be sent even further away from his mother, Donna Larsen.

The machine — and the rest of his possessions — arrived safely. “Now, I see mountains, trees and animals from my cell: deer, Canadian geese and a family of hummingbirds that have built their nest in my window,” he says, from his new destination California State Prison, Sacramento. As for his mother, her commute to visit him is only about an hour longer (with good traffic).

In a telephone conversation with EL PAÍS, Larsen — who enrolled in law school when her son was convicted, so that she could prove that he’s as “innocent as a newborn” — explains that she’s been closely following all of the inmate transfers, beyond just her son’s. After speaking with many of those transferred, she believes that, “in general, the balance has been good.” Larsen is an institution among relatives of California death row prisoners. In her eighties, she says that many of them call her “grandma.”

On the day of his interview in San Quentin, Kevin Cooper said that the transfer didn’t bother him. “I’m too old to worry about anything. If I survived this hell, I can handle anything. A prison is always a prison.” A guard had brought him in handcuffs from the East Block, the five-story yellow building that houses death row. There, he lived in a 48-square-foot space without windows. He had a sink, a toilet and a metal bed. Whenever he wanted to write, he would remove the mattress, to use the structure as a desk.

Cooper entered the cell within the visiting room. From the outside, guards removed his handcuffs, before locking the cage.

To access San Quentin, clothing of certain colors isn’t permitted. Mobile phones, cameras and recorders are also prohibited. As a result, in the middle of the conversation — which lasted just over two hours — a prison official took a picture of Cooper for this newspaper.

Cooper spoke about many things while eating reheated spicy chicken wings. He discussed the solace he has found in books and art: his paintings are pleas against the death penalty and racism, although the new prison has taken away his brushes. He mentioned the emotional shields he has developed over the decades. “I have no friends in here: loneliness is my oldest companion,” he said quietly.

When asked about the first thing he would do if he were ever to be released, he replied: “As someone oppressed, I would join a demonstration. For example, in favor of the Palestinian people.”

Above all, during his conversation with EL PAÍS, Cooper, 66, reviewed his life. It was split in two by a fateful night in June of 1983, when Doug and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter Jessica and an 11-year-old friend who was spending the night were murdered with knives, axes and an ice pick. They were killed at their house in the wealthy neighborhood of Chino Hills, near Los Angeles. Josh — the youngest son — survived, despite his throat having been slit.

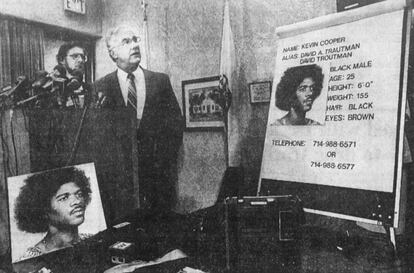

In his first statement to the police, eight-year-old Josh Ryen indicated that three white people were responsible for the massacre and later suggested they were Latino. Initially, when Cooper’s photograph came on the TV, Ryen specifically said that it was not him. Later on, however, his perceptions changed.

Cooper — a 25-year-old Black man with a criminal record — had hidden in an empty house just over 150 yards away from the Ryens’ residence. This was after he had walked out through a hole in the fence of a minimum-security prison where he was serving time for robbery. “That was the worst decision of my life,” he recalls.

He spent two nights in that abandoned house. From there, he unsuccessfully called a couple of female friends to lend him money. He claims that he continued on his way to Mexico before the murders. When the police learned that a fugitive was on the loose in the area, officers — pressed to solve a case that horrified the country — abandoned the rest of their leads and decided that Cooper was the culprit. That same year, the sheriff in charge of the investigation was up for re-election. It took him just four days to close the case.

The suspect was, at the time, on the run in Tijuana. “When I saw on TV that they were looking for me, I was scared by the way they talked about me,” he remembers. Cooper and his supporters — including activists from Amnesty International — have been questioning the investigation for the past four decades. In an initial search, the police didn’t find any incriminating evidence in the empty house. But the next day, they did: a green button from a prison uniform (it was later learned that the suspect was wearing a brown jacket), as well as the sheath of an axe.

Blood and cigarette butts

The Ryen station wagon — found about 50 miles from the crime scene — had traces of blood on three of its four seats. However, the jury that found Cooper guilty didn’t apparently consider the improbability of a single person having stained three seats, nor did the jurors wonder how he had managed to inflict 140 stab wounds on the victims single-handedly. In an initial search, police didn’t find any of the suspect’s fingerprints in the vehicle. But again, during the second check, the clues suddenly appeared: three cigarette butts of the same brand that Cooper smoked in the abandoned house.

In the summary of the case, there’s evidence of an astonishing phenomenon: those butts changed size over the years.

Another thing that draws attention in a case full of shadows is the fact that a woman called the police saying that her boyfriend — a white man — had shown up on the night of the murders with overalls covered in blood. She later handed them over to San Bernardino Sheriff Department, but the deputy decided to destroy that piece of evidence. In 2004, Sheriff Floyd Tidwell — suspected of having built a corrupt network while he was the county’s police chief — pleaded guilty to keeping more than 530 guns confiscated by his officers over the years.

Cooper’s trial was held in San Diego, with protesters holding racist signs, and a stuffed gorilla hanging on a pole with a noose around its neck with signs reading “Hang Kevin.” He complains that his court-appointed attorney “didn’t do enough” and that he “wasn’t prepared for such a complex case.” The jury — made up of 11 white citizens and one Black— found him guilty and recommended the death penalty. Since then, he has exhausted all possible appeals.

In 2004, he was almost executed. With three hours and 42 minutes left before the lethal injection, the order came from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals — with jurisdiction over the Western United States — to stay the execution. “The day they almost killed me was one of the most unreal of my life, like watching a movie starring someone else,” Cooper recalls. “They asked me what I wanted my last dinner to be, but I refused to choose. It’s cruel: how do you make someone you’re going to kill eat a meal? I looked at the clock and also at the eyes of my executioners. When they found out [that my execution] was being postponed, I felt the anger on their faces.”

Shortly before that, a powerful law firm — Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe — began working on his case, pro bono. This is a constant in capital punishment cases in the United States. When the accused is being trapped in a judicial system — from which it’s almost impossible to escape from afterwards — the defense is often flawed. Hence, when the alternatives are exhausted, sometimes brilliant lawyers come in to do unpaid work.

René Kathawala, a lawyer at the firm, explains in a telephone interview from New York that they’ve been asking (without success) for the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department to hand over any files they have related to Cooper’s case. “It would shed light, for example, on why the other leads were discarded. Or about where the evidence collected at the Ryen house went. Or about the hypothesis that everything was due to settling scores [having to do with] a horse sales business. Kevin had no reason to kill that family,” he emphasizes.

Kim Kardashian’s visit

Since a federal appeals court stayed his execution, Cooper’s cause has gained prominent followers, including William A. Fletcher — a senior judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit — who wrote a 100-page dissenting opinion in 2009 that began with the following line: “The state of California may be about to execute an innocent man.”

Other visitors include Kim Kardashian — who visited Cooper in at San Quentin — or the influential New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, author of a detailed article on the case as an example of a “broken judicial system.” In it, he spoke with the parents of the murdered boy who was spending the night at the Ryens’ house — who have no doubts about Cooper’s guilt — and he opined that new DNA tests should be carried out.

These tests were ultimately authorized, but the results were of little use. It was once again proven that the hairs found on the victims’ hands were not those of the convicted person, but there was no way to link them to any other suspect. An orange towel yielded a complete DNA profile, although investigators never found the person it belonged to. And it wasn’t possible to extract enough genetic material from a tan T-shirt, because it was degraded after so much time had passed. An earlier examination identified drops of Cooper’s blood on that garment, as well as traces of a chemical preservative called EDTA, which is used to prevent samples in test tubes from spoiling. For those who defend Cooper’s innocence, this can only mean that the sheriff planted those remains.

In 2019, Gavin Newsom — the newly-elected governor of California — declared a moratorium on all death sentences. He also had San Quentin’s execution chamber — the infamous “green room” — dismantled. Doolin remembers that he saw the news on television in his jail cell. All the people on East Block spontaneously cheered.

The governor also ordered an “innocence investigation” into Cooper’s case by the international firm Morrison & Foerster, the results of which were published in January of 2023. The report concluded that the evidence of his guilt was “extensive and conclusive.” The 243-page text also said that there was no DNA evidence that “points to anyone else as being guilty.”

“That was one of the worst setbacks of my life,” Cooper laments.

“It was a superficial and absurd job, of deliberate incompetence,” Kathawala scoffs. “It seemed as if they wanted to ambush him. [The report] took us all by surprise, and not just because of the content. They published it on a Friday before Martin Luther King Day weekend. And they gave it to us 20 minutes before sending it to the media. So, the initial coverage — very extensive — was very damaging for Kevin. [Morrison & Foerster] relied only on the documents from the [previous] trials. They didn’t even subpoena those who participated in the investigation to testify.”

Since the report’s publication, the law firm has declined to publicly comment on its conclusions, or on the methodology that was utilized.

After this, there are only two last resorts for Cooper: that Newsom decides to exonerate him through an executive order (“unlikely,” Kathawala believes) or that the recently-approved Racial Justice Act — with retroactive effect — allows any conviction to be appealed if it can be demonstrated that there was some type of racial prejudice in the legal process.

A racist system

To try to prove that this is what happened to him, Cooper has had the help of professor and author Lara Bazelon for the past few months. She is the director of the Criminal Juvenile Justice and Racial Justice Clinics at the University of San Francisco. “I think Kevin fits neatly with what that law provides. There were many irregularities [in his case]. The main one is that the prosecutors always refused to share [the papers stemming from their investigation]. There’s no way of knowing how many Brady violations were committed, but it’s clear that there were many,” Bazelon tells EL PAÍS, in her office in San Francisco. The Brady doctrine emanates from a historic ruling by the Supreme Court in the 1960s: it obligates the prosecution to share any exculpatory information with the defense.

Statistics confirm that California’s capital punishment industry — which is estimated to have cost taxpayers $4 billion since its reintroduction in 1976 — disproportionately affects minorities. While only 5% of the state’s population is Black, more than a third of those who are sentenced to death are African-American. Black detainees are — according to Morgan Zamora, at the Oakland offices of the non-profit Ella Baker Center for Human Rights — between five and nine times more likely than other races to suffer this fate. In the case of Latinos, they are between three and six times more likely to be sentenced to death. Last year, California was the second state — after Florida — in the number of death sentences. All of these were handed down to Black and Latino defendants.

This past April, awareness of “systemic racism” led Jeff Rosen — the district attorney for Santa Clara, California — to overturn 15 death sentences in his county, which is located in the heart of Silicon Valley. He instead re-sentenced the 15 death sentenced men to life in prison, without the possibility of parole.

“It seems to me that it’s already a harsh enough punishment: spending your entire life behind bars and dying in there. And, please, don’t take me as someone who’s soft on crime,” Rosen explains, in his office in the city of Santa Clara. “After the murder of George Floyd [at the hands of a white police officer in 2020], I realized that something wasn’t right [with this system].”

His change of mind was also influenced by a visit he made to the National Lynching Memorial in Alabama. This opened his eyes, he says, to “the certainty of mass incarceration as a continuation of slavery and segregation,” as well as the suspicion that there’s something perverse about the system itself, which delays executions for decades. “If someone commits a horrible crime at age 25 and you don’t execute him or her until age 65, are they still the same person? I don’t think so.”

Rosen also warns that requiring capital trials to be decided by juries unintentionally contributes to racism. “To be accepted [on the jury], candidates have to make assurances that they feel morally capable of applying [the death penalty]. And who tends to overwhelmingly say ‘yes’? Conservative white men.”

Rosen isn’t the only district attorney to take the abolitionist path in California as of late. The day before he re-sentenced the 15 death penalties, District Attorney Pamela Price of Alameda County received a court order to review the 35 capital sentences in her jurisdiction, over suspicions of prosecutorial misconduct. Various prosecutors were accused of systematically excluding African-Americans and Jews in jury selection. And, this past April, several prominent legal and civil rights organizations filed an extraordinary writ petition at the Supreme Court of California, seeking to abolish the death penalty based on racial bias. Additionally, in January of 2024, the SB97 law came into force, drafted to simplify and accelerate the process of reviewing wrongful convictions.

Both Doolin and his mother have their hopes pinned on that option. “I trust that, upon reviewing the case, the judge will determine that I’m innocent and deserve to be released,” he says.

Natasha Minsker — an attorney and consultant on criminal justice reform and policy — feels that there’s a paradigm shift taking place. Is California witnessing the slow death of the death penalty? “I think so,” she says cautiously. “Although it’s also true that this agony has been going on for too long, about 10 years now,” she argues, in a telephone interview from Sacramento — the state capital — where she attempts to lobby legislators and the governor’s office in favor of reform.

Newsom could grant a universal pardon before leaving office (his second and final term will end in 2027). The state’s anti-death penalty activist community dreams about that possibility, although such a move may not bode well for his presidential aspirations. If he were to do it, this would mean that all those sentenced to death would no longer be condemned, but it wouldn’t imply the abolition of capital punishment: the law dictates that something like this can only come about through a popular referendum.

“I’m not giving up hope,” Minsker vows. “I know that the governor is very committed to ending the death penalty in California. I trust he will do everything he can before leaving office.”

According to this lawyer, the dismantling of San Quentin’s death row demonstrates Newsom’s commitment. And, if it’s true that the death penalty is dying in California, the East Block — with its tiny cells and nightmarish atmosphere — may soon serve as a chilling reminder of a past time. A memory of a place in a beautiful corner of the San Francisco Bay, where some men, as Cooper would say, were “not allowed to be human.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.