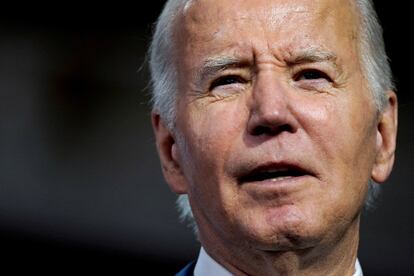

US House of Representatives prepares to vote on impeachment inquiry against Biden

Kevin McCarthy ordered the probe in September, but Republicans now want it to be endorsed and formalized by the lower chamber

When Republicans took control of the U.S. House of Representatives a year ago, one thing was clear in their minds: they wanted to make Joe Biden’s life miserable. From the get-go, they proposed impeaching the president, even though they had no compelling arguments to do so. In the end, former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — in an effort to appease hard-right Republicans — ordered an impeachment inquiry into Biden in September. In doing so, McCarthy broke his own promise to put the decision to a vote on the House floor. Now, the Republicans want that vote to happen, and it may take place on Wednesday.

While the impeachment inquiry formally began in September, the probe into Biden has been going on for years. Under the Donald Trump administration, Republicans tried to insinuate that Biden was involved with the foreign business dealings of his son, Hunter Biden, when he was vice president. They accused Biden of bribery, abuse of power and influence peddling, but to no avail: there was no evidence of such crimes. Now it is Trump’s most loyal allies in Congress who are pushing the investigation into Biden.

Since taking control of the House, Republicans have been summoning witnesses who they believed could implicate Biden, but with no success. In September, McCarthy ordered three House committees to open an impeachment inquiry, alleging a “culture of corruption” in the Biden family and hinting at accusations. No evidence, however, was provided to support these claims. McCarthy did not even put the initiative to a vote in the House, as he believed Republicans in swing districts would vote against it, since they saw no reason for such a step.

The committees have achieved little in these first months of work. They issued requests and subpoenas that have gone nowhere. In the first hearing with witnesses, even those who had been summoned by the Republicans said that they saw no reasons for an impeachment. The investigation also faces an additional difficulty. Since the inquiry was not approved by the House, it is not clear whether the subpoenas are legally binding. The Republicans summoned Hunter Biden to appear in a closed-door hearing on Wednesday, but he said he would only attend if he could testify publicly. Although some members of Congress have threatened to hold him in contempt, the truth is that the subpoena does not appear to be legally binding.

The White House has also refused to respond to requests and subpoenas, alleging the inquiry lacks the legitimacy as it has not been formally approved by the House.

The new speaker of the House of Representatives, Mike Johnson, supports putting the inquiry to a vote precisely for legal reasons. “The House has no choice if it’s going to follow its constitutional responsibility to formally adopt an impeachment inquiry on the floor so that when the subpoenas are challenged in court, we will be at the apex of our constitutional authority,” Johnson told reporters in early December. He made the same argument in an article published in USA Today on Tuesday.

The White House went to great lengths to present the opening of the investigation as a demonstration of Republican extremism. The White House distributed a 14-page report in September that tried to dismantle the allegations one by one. The report relied heavily on statements by Republican members of Congress who admitted that no wrongdoing had been proven, and also highlighted how some accusations had been manipulated.

But the second indictment against Hunter Biden — who is accused of evading taxes while leading a life of luxury — has given the Republicans a boost. Hunter Biden does not hold office and cannot be impeachment. What’s more, members of Congress have failed to prove that the president benefited in any way from his son’s businesses. But the indictment against Hunter Biden has brought the Republicans together, and made it easier for them to vote in favor of the impeachment inquiry, even more so when, in practice, it is a formality to give legitimacy to an investigation that is already underway.

The Republicans have a very slim majority in the House (221-213), so if any House Republican votes against the move, they may find that another candidate endorsed by Trump will challenge them in the primaries. The vote is in principle scheduled for Wednesday, as Thursday is the last House session before the Christmas break.

Hunter Biden, meanwhile, has filed a series of motions calling for the gun charges brought against him in Delaware to be dismissed. In the different motions, the president’s son argues that he is a victim of political persecution, defends the validity of the plea deal he reached with the prosecution and says he is protected by the right to bear arms, which is enshrined in the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The Republicans are looking to politically torture Biden and believe that an impeachment inquiry will help counterbalance the legal woes facing Donald Trump ahead of the November 5 presidential elections next year, in which the entire House of Representatives and a third of the Senate are also up for grabs.

Impeachment protocol

Articles 1 and 2 of the U.S. Constitution regulate the impeachment of public officials. In the case of federal public officials, it is the House of Representatives that presents the articles of impeachment, while the trial takes place in the Senate. Article 2, Section 4 states: “The president, the vice president, and all civil officers of the United States shall be removed from office upon impeachment for and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

There are also state impeachment trials, such as the one that took place in Texas against its attorney general, Ken Paxton (he was later acquitted).

A pre-impeachment investigation is aimed at elucidating whether there is enough material to go forward with the proceeding. A formal investigation of this type is not required before an impeachment, but it is common practice.

After the inquiry is completed, the usual next step is for a commission to specify the articles of impeachment — the criminal equivalent of the charges or accusations — and to submit them to a House vote. If they are formulated and approved by the House, it would be the Senate that would carry out the impeachment trial.

Chief Justice John Roberts would preside over the trial, lawmakers appointed by the House of Representatives would act as prosecutors, while senators would serve as jurors. According to the Constitution, “no person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the members [of the Senate] present.” In other words, 67 votes would be needed if all 100 senators were present. Democrats have a majority of 51 to 49 in the Senate.

An impeachment is an exceptional procedure. Only three presidents throughout history (Andrew Johnson, in 1868; Bill Clinton, in 1998, and Donald Trump, in 2019 and 2021) have been impeached by the Senate at the request of the House of Representatives. All three were acquitted.

Trump’s first impeachment trial is related to the current inquiry against Biden. It was born from Trump’s attempts to seek Ukraine’s help to smear Biden, who was then the favorite to win the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. Trump wanted to hurt Biden’s chances by using his son’s business dealings against him. In December 2019, the House of Representatives accused him of abuse of power for pressuring Ukraine to investigate his political rival and of obstruction of Congress for ordering officials to refuse to testify. He was acquitted of both charges by a 48-52 and 47-53 vote, respectively.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.