The downfall of John Cusack: What happened to the best-loved actor of the early 21st century?

The star of ‘High Fidelity’ and ‘Being John Malkovich’ became an indie sensation thanks to his roles in critically acclaimed films. So why has his career been floundering over the past decade?

A few weeks ago, just before a playoff baseball game between the Chicago White Sox and the Houston Astros, Dave Williams – a blogger and podcaster associated with the website Barstool Sports – approached actor John Cusack in a parking lot. The scene, which was recorded on a cellphone, saw an angry Williams accuse Cusack of betraying his team, the Chicago Cubs, the rival club in the capital of Illinois. Cusack got out of the predicament without too many problems, reminding the provocateur that he had followed the White Sox for years and knew more about the history of the team than he did.

That’s the last news that we’ve had from Cusack, apart from what the actor posts every day on Twitter, a social network where he is very active. On his Internet Movie Database (IMDB) page, there are just two future projects: Pursuit, an action movie that promises little, and another titled My Only Sunshine, in which he would share the screen with J. K. Simmons of Whiplash fame. There is, for now, no release date for the latter title.

“I haven’t really been hot for a long time,” he confessed during an interview with UK daily The Guardian back in 2020. This acceptance of his situation in the industry makes his decline as an indie leading man all the more ironic.

With the arrival of the 21st century, Cusack began a good run. In the 1980s, thanks to films such as The Sure Thing (1985) and One Crazy Summer (1986), he discovered that there were too many (very attractive) competitors for the roles of teen star; in the 1990s, he specialized in more tortured characters, but always walking the line of what was acceptable for the general public. Cusack appeared to be destined to play a cultured and disoriented type, a romantic hero with a foot in the arty and commercial. He wasn’t your typical leading man, but he had an agreeable and intriguing face. He didn’t bring particularly dazzling characters to life, but they were adorable and funny.

Cusack was the stereotype who perfectly fitted the climate of those times, when metrosexuality was on the rise and a guy like him was valued. He was the embodiment of an alternative who was barging his way into the multiplexes that showed blockbusters; the romantic hero who was accepted by those who looked on romantic comedies with disdain; the actor who you could fall in love with on the pretext of his intellect but who at the same time was anything but ugly.

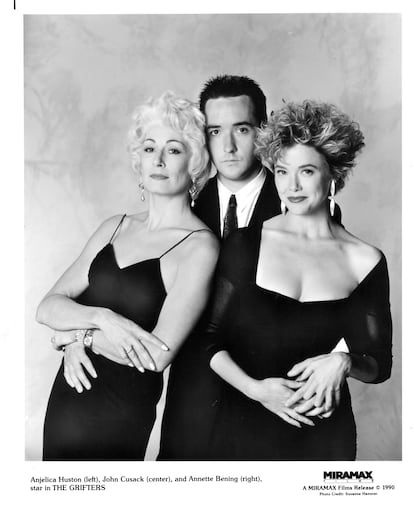

Among his standout films in this second stage are The Grifters (1990), where he portrayed a conman with a romantic air, Bullets Over Broadway (1994), in which he played a young playwright who sells his soul to the Mafia in order to see his work staged in a large theater, and Grosse Pointe Blank (1997), with the role of a hitman who has been sent on a mission in Detroit, where, by chance, his high school reunion is taking place. When his next two jobs arrived, the critics and public alike bowed down before him.

The first was Being John Malkovich (1999), which had a script by Charlie Kaufman and was directed by Spike Jonze. It was a black comedy with fantasy elements, and saw Cusack play a puppeteer who discovers a door leading directly to the brain of actor John Malkovich.

The second, High Fidelity (2000), was based on the novel of the same name by Nick Hornby, and follows a thirtysomething owner of a record store as he tries to win back the love of a girl who has just left him, revisiting the errors of his five worst relationships along the way. The film was a major success, and left its mark on a whole generation of men who love indie music.

That said, seen from a modern-day perspective, Cusack’s character, Rob, has not aged that well – in particular when compared to its subsequent adaptation for the small screen, with Zoë Kravitz taking the lead role this time around. These days, Rob comes across as an interesting example of toxic masculinity. “You can make any argument you want about the character, but was that character true?” he asked during an interview for The New York Times in 2020. “Is that how people are? I’m glad that people have changed their view of Rob. I mean, he was an [expletive]. We all are. If somebody was writing that Rob was a passive-aggressive womanizer, I’d be like, ‘All right, somebody got it.’ I wanted to reveal the flaws of the character.”

The success and credibility of Cusack were such that film critic Roger Ebert positively gushed about him: of 55 films, he said, not one of them was bad. But that was in 2010. Since then, he has appeared in 25 movies, most of which have gone completely unnoticed by the general public. They were either straight-to-DVD releases or on streaming (at a time when that wasn’t what it is today), and rarely did they please the critics. Finding explanations for this is not easy. Maybe he’s too old now for the romantic comedy roles he took in the 1990s, or perhaps he has made a few bad decisions when choosing work.

It’s also possible that his image off the screen and his lifestyle have not exactly favored his career. Cusack is far from the typical Hollywood star whose private life – whether it’s scandalous or perfect – almost forms part of a promotional strategy to sell their new movies. He’s never been married or had kids, and the tabloids have no clue about his personal affairs. When he was younger, he was linked to Jennifer Love Hewitt and Uma Thurman, but years have gone by without news about his romantic partners. In an interview with the magazine Elle, in which he was asked about never having married, his reply was blunt: “Society doesn’t tell me what to do.”

What’s more, for some time now he has lived away from Hollywood. In 2016, he sold all of his properties in California after getting rid of his house in Malibu, which he had bought in 1999, and he returned to his home state, Illinois, where he purchased a 240-square-meter loft in a 52-story building in the middle of Chicago. He often takes pictures of the sunset from there, and later shares them on Instagram.

In no uncertain terms, he attributes the move to his disdain for the movie business. “[Hollywood is] a whorehouse and people go mad,” he said during an interview for The Guardian in 2014, after the release of Maps of the Stars.

Another of the possible reasons behind his ostracism is that his involvement in politics goes beyond being the face of an NGO or a UN Goodwill Ambassador. The actor is one of the founders of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, an organization that finances and supports freedom of expression and press freedom all over the world, and that was born after Visa, MasterCard and PayPal stopped working with whistleblower site WikiLeaks, threatening the very existence of that organization.

In relation to this same activism, in 2014 he traveled to Russia with the writer Arundhati Roy and economist Daniel Ellsberg to interview Edward Snowden, the former intelligence consultant who leaked classified data from the National Security Agency and was forced to flee the United States. That visit gave rise to the book Things that Can and Cannot Be Said: Essays and Conversations, which was authored by Cusack and Roy.

And this is not the only way that the actor expresses his political commitments. He has done so on many other occasions, such as his active participation in the protests after the murder of George Floyd, an incident that galvanized the Black Lives Matter movement. Or thanks to his role as a scourge of the far right via Twitter, where he expresses his most critical side and describes himself as an “apocalyptic shit disturber and elephant trainer.”

A frustrated return to center stage

Just a year ago it looked as if things were going to change. After having stayed away from the world of television for practically his entire career – bar a brief appearance in sitcom Frasier in 1996 – the actor agreed to take on his first show. It was a US remake of British series Utopia, in which he played a biotechnology magnate – an Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg type, exactly the kind of person he usually pillories on his Twitter account.

The move to television fascinated Cusack, or at least that’s what he said in his interviews at the time. Perhaps he was expecting that his career would resurge on other screens, as has happened for many other actors of his generation. But while the critics applauded his performance, the show was canceled by Amazon and will not be returning.

At least we still have his Twitter feed, where every night, without fail, he expresses his anger for major corporations, the regime of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the continual announcements from former US president Donald Trump of his return to politics, or the bloated defense budget in the United States. It’s a hobby that, while not being exactly positive for his mental health, he confesses is difficult to abandon. “I would love to think about other things,” he confessed in 2020 when speaking to The Guardian. “Poetry. Love. Anything else. But that’s just not the times we’re in. [...] Maybe being outspoken hurts your career… I’m just aware it helps me sleep better at night, knowing that I wasn’t passive during this time.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.