Why Josh Hartnett left Hollywood, and why he’s back: “I decided to have a life”

Crowned ‘the new Tom Cruise’ in the early 2000s after a run of hit films, he chose to leave fame behind. Now Guy Ritchie is bringing him back into the spotlight for his first mainstream feature in 14 years

Two decades have passed since Josh Hartnett was crowned Hollywood’s hero: the new Tom Cruise, the new Gary Cooper, the new Leonardo DiCaprio. “I was on the cover of every magazine. I couldn’t really go anywhere. I was alone. I didn’t trust anyone,” he recalled in a 2014 interview. The accolades felt undeserved, and he was then considered ungrateful by the studio publicity machine trying to hype him. “They looked at me as someone who had bitten the hand that fed me,” he has said. “I tried to find smaller films I could be part of and, in the process, I burned my bridges at the studios because I wasn’t participating.”

These days, Josh Hartnett lives a quiet life in Surrey, England, with his wife Tamsin Egerton and their three children. But he is dicing with Hollywood once again after a 14-year break, and at age 42 he will appear alongside Jason Statham in the Guy Ritchie thriller Wrath of Man. Ritchie needed an urgent replacement for an actor on the film, and he knew that Hartnett lived close to the set. Improvising his character on the fly, Hartnett now says it was one of the best experiences of his career.

According to Hartnett, he never really left the movie business, but just adapted to the demands of more pressing issues. “I didn’t really take any major hiatuses that were planned, I just had kids,” he told Yahoo Entertainment recently. “I started doing smaller films, [since] the films didn’t take me away from the kids very often.” Turning his back on Hollywood remains a fascinating subject for many fans, and a telling story of how show business works.

Josh Hartnett decided to become an actor while working in a video store, thanks to films such as Trainspotting, 12 Monkeys and The Usual Suspects. He began studying acting at the State University of New York, but when he wrote a letter to the dean saying that the evaluation system stifled students’ creativity, he was expelled.

When he later landed in Los Angeles, his manager Nancy Kremer was waiting for him at the airport with 80 auditions scheduled over three weeks (normally actors might do four a week). From those sessions he was cast in Halloween H20, The Faculty and The Virgin Suicides – all stone-cold hits. His role as heartthrob Trip Fontaine in the latter 1999 film cemented his place as a pop-culture icon, with the camera panning from boots to dodgy wig.

The press fawned over him. “Ready for Takeoff” read the cover of People magazine ahead of the release of Pearl Harbor. “The guy will have beautiful women camped out on his front lawn for months,” said his co-star, Ben Affleck. Hartnett was hesitant to star in a blockbuster because he feared big-name directors wouldn’t take him seriously, but his father convinced him. Fame is temporary, he told his son, but regret is permanent.

In June 2001, Vanity Fair published a profile entitled “The Making of Josh Hartnett,” focused on his crossover into megastardom. The article’s thesis was that Hartnett didn’t seek fame because he was a sensitive rebel in love with the Beat poets, but he shone so brightly that stardom was inevitable. “When he went out, every single call, he got a callback on, which is pretty much unheard of,” his manager was quoted as saying. “And on top of that, casting directors were calling other casting directors telling them that they should meet him. That’s a huge buzz you can’t buy in Hollywood. That’s just a gift from the heavens.”

The gushing continued at length. “If all goes according to plan, by the Fourth of July, Josh Hartnett will be a product-moving, culture-bridging heartthrob on the order of Leonardo DiCaprio, or thereabouts,” the piece went on to say. “I kept telling him,” producer Jerry Bruckheimer is quoted as saying, “when this movie comes out, it will change your life.’ He said, ‘I know, I know.’ But he doesn’t really know. He has no idea what he’s in for.... There’ll be girls and people wanting his autograph running after him.”

In the piece, Hartnett recounted how director Michael Bay kept forcing him to smile more. “It was one of those directions that, as an actor, you go, ‘How does that work for me as the character? I can’t just go out there and smile.’ So it was pretty frustrating,” he said. It was perhaps a sign of what was to come. “I never really understood how the movie stars would do their charismatic thing, and they definitely tried to teach me.”

Looking back to that interview in a recent article in The Guardian, Hartnett shuddered. “Oh, that was an awful piece… Was there even a quote from me in it, or was it just everyone talking about how hot I was? People got a chip on their shoulder about me after that. They genuinely thought I’d been thrust on them. It was a very weird time.” Being compared to Tom Cruise and Julia Roberts was “insane,” he added. “It was actually an interesting look at the nature of fame. If only it wasn’t about me.”

Pearl Harbor was the sixth highest-grossing film of 2001, in what would be a success for any film except this one, which also received devastating reviews. So, after four years of working every day, Hartnett returned to Minnesota and spent 18 months without reading a single script. He wanted so badly to reconnect with his old life that he started dating his high school sweetheart again, but instead of moving in with his parents in Saint Paul, he bought a million-euro mansion on Lake of the Isles.

Suddenly, he was prey for the wolves. “Modesty in a good-looking young man can be attractive, but Hartnett needs to develop a screen personality,” wrote David Denby in the New Yorker. “Just a bad-haired actor who got lucky,” snarked Anna Day in The Mirror. By treating him as a commodity, Hollywood speculated on Josh Hartnett until his real value, whatever it was, ceased to matter. His career was perceived as a failure only because he failed to live up to the expectations the industry had placed upon him itself. The 2002 sex comedy 40 Days and 40 Nights would be his first and last leading man movie.

Cracks started to show. When Hartnett was promoting the 2003 action film Hollywood Homicide with Harrison Ford, he didn’t mince his words about his co-star. “We had our pluses and minuses, he tested me and I hated him for a while. He would pick on me for my choices, like ‘That’s not a cop’s hairstyle.’ Other than Brad Pitt in Shadow of the Devil [with whom Ford also argued constantly], I’m the second young guy he’s worked with in his entire career. So when I got into his territory he started nudging. He may be the nicest guy to everyone else, but with me he could sit in the car for an hour without saying a word to me,” he told the media.

That same year, his agent came to him with sensational news: Hartnett would play the new Superman. He turned it down. He had better things to do than spend the next decade tied to a contract, even though the offer was rumored to be $100 million for three movies. He again feared missing out on opportunities to work with prestigious filmmakers. “At the time, it was so obvious to me to turn it down,” he said earlier this year. “I was being offered movies by the very top directors. And Superman was a risk. Yes, there was a lot of money involved, but I didn’t think that was the be-all and end-all.”

It got worse when he became the guy who not only turned down Superman, but Batman as well. This time, he regretted it. “I’ve definitely said no to some of the wrong people,” he said about rejecting the lead role in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins. “I said no because I was tired and wanted to spend more time with my friends and family. That’s frowned upon in this industry… I learned my lesson when Christopher Nolan and I talked about Batman. I decided it wasn’t for me. Then he didn’t want to put me in The Prestige. They not only hired their Batman for it, they also hired my girlfriend [Scarlett Johansson] at the time.” Watching Christian Bale take the role and avoid being typecast as a single type of actor made him reflect. “I was so focused on not being pigeonholed and so scared of being considered only one thing as an actor.”

When Brian De Palma’s The Black Dahlia came out in 2006, Hartnett still had enough star power to make magazine covers, but a failed actor narrative was now part and parcel of his public image. He was now “a recovering teen idol” making “a comeback,” according to a GQ article written about his role in the film. “Let’s be honest, Josh Hartnett was foisted upon us… This is how it went with Josh Hartnett. We were just told that he was a star. His ubiquity came so suddenly that by the time we could put a name to his face (the square jaw, the safety-scissors haircut, the vaguely otterish good looks) we were already sick of looking at it.” By then, Hartnett’s production company had closed without developing a single project. He was 28 years old at the time.

And so 10 years passed, between indie films and shorts. In The First Monday of May, the 2015 documentary about the Met Gala, organizer and Vogue editor Anna Wintour is shown looking at a board with various photographs of celebrities. Suddenly she stops at one. “Who is this?” she asks. “Josh Hartnett,” her assistant replies. “And what has he done lately?” continues Wintour. “Nothing,” comes the answer. Wintour rips the photo off the board.

That year, Hartnett returned to the limelight with the series Penny Dreadful, where he aimed to be taken seriously beyond his looks. He fired his manager, made the move to Surrey, and began talking openly about his years at the pinnacle of Hollywood fame. As more years have gone by, he has revealed more and more. “There was a time I was considered quite a commodity in the business and I wanted my character to chew gum in a scene,” he told the men’s style publication Mr Porter. “It was run up so many flagpoles and it was the subject of conversation for days and in the end, they decided just no. They had an idea of what they thought they could sell with me in it, or what the persona is that people wanted to see from me. And it didn’t involve chewing gum.”

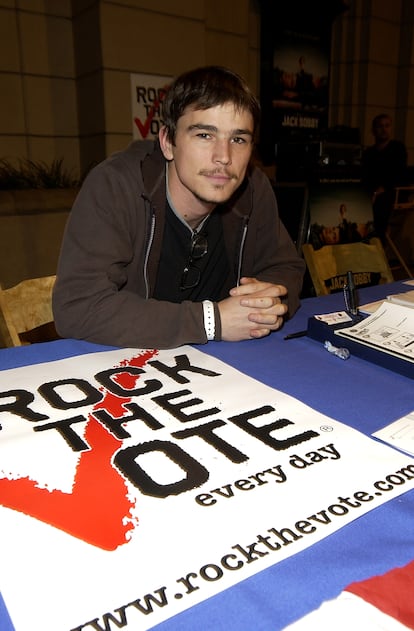

One of his biggest regrets was getting into politics at the age of 25. He supported Democrat John Kerry’s failed presidential campaign, showing up at rallies in Iowa without knowing anything about Iowa, and visiting schools in Republican neighborhoods where kids dismantled his arguments.

Hartnett believes that in Hollywood most people leave their old lives behind and “just socialise with people who are in the industry, because they’re gonna hire you for the next job.” He hasn’t forgotten Harrison Ford. “The guys who are on top are terrified that someone’s coming up behind them. If that’s your real ambition, to be on top all the time, you’re going to spend your whole life looking over your shoulder. I never wanted that,” he clarified.

So what is Josh Hartnett’s ambition? “I decided to have a life,” he said. “To put that first. That was always my goal.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.