Life at the US naval base in Rota: A union of two worlds

Created by decree in 1953 under the late Spanish dictator Franco, this singular spot has developed a hybrid personality that combines languages, cultural elements and mutual interests

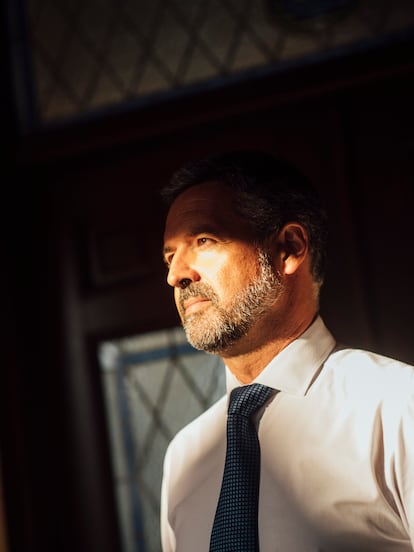

Felipe Benítez Reyes, a 61-year-old native of Rota, in Spain’s southern Andalusia region, was not even born when this rural outcrop on the Atlantic coast of Cádiz became a joint military base designed for Americans. Now, it is difficult to think of Rota without the naval base.

Spanish dictator Francisco Franco certified this strange union by simply pointing his finger at the territory where the base was to be installed, or so the story goes, and lo the place was born. Writer Benítez Reyes says the base became “an industry” for the town that hosts it. “That was the case in the early 1950s and I think the perception is still the same today,” he explains.

Soldiers from two countries live side-by-side there, which might seem to present identity issues but doesn’t faze the commanders of either nation. The local residents sleep through the constant airplane noise, and speak English or Spanish just as readily, the latter with a heavy Andalusian accent.

Antonio Maña Zafra, 97, is perhaps Rota’s oldest resident, and was an astonished local doctor when Franco arrived alone, at 4:30pm on October 14, 1953, at Rota’s Luna castle. The dictator asked some nuns to show him the way to the stairs of the tower. From there, he pointed an index finger at where he wanted “the Base” to be built. Maña Zafra was with a colleague, Dr Rodríguez Rubio, and they both listened to Franco’s high-pitched voice (“unbecoming of a general”) which ordered vast swathes of countryside and sea looking out to infinity to be transformed. Land was appropriated, farmers paid off and builders and personnel began to arrive from all over. Rota “was on the up,” says Maña Zafra.

Until then there had only been “a few countryside inns,” he recalls, and farmers were offered the chance to move to a town created to accommodate them: Nueva Jarilla. “They, in turn, rented out the houses to the Americans, and then our social life kicked off, with the newcomers dancing with women from Rota,” says Maña Zafra. Integration was quick, with some stark differences. “The Americans had those big cars, when we did not even have a Fiat 600,” he says. It was like the 1953 Spanish film ¡Bienvenido, Mister Marshall! (or, Welcome, Mister Marshall!) about US diplomats coming to a small rural town. But there was a key difference: “In that film the Americans left, but here they stayed, and mixed in with the people from Rota and with those who came from [the rest of Spain], because here there were no specialists in heavy machinery,” says the 97-year-old.

Initially, according to Maña Zafra, “the customs clashed; the Americans came with the fame that the movies gave them, and here the people were very peaceful. But we adapted, and they adapted to us. They liked our beer, which they ordered by the case, and bars, cabarets, dance halls and billiard rooms, all filled up, and all done up in the American style.” The soldiers “left monstrous tips,” and word got out of their generosity. “[There were] 11,000 boys in their twenties, so imagine how many women came from all over.”

One day, Franco’s governor asked Maña Zafra, who would end up becoming mayor of Rota between 1963 and 1970, to tell him why the town was full of prostitutes, adding that Franco’s wife was “obsessed” with the issue. He does not remember any big fights, but he does remember the day of Franco’s death, when the Americans were urgently summoned to take cover at the base. “Then nothing happened, [but] they thought there was going to be a revolution.” Demonstrations against NATO would follow, and many more. By then, Maña Zafra “had already seen it all.”

Rota is a very peaceful place, sitting beside a complex shared by Americans and Spaniards by Franco’s design and, later, by agreement of the democracy that came after him. Maña Zafra says, and many agree, that this coexistence has protected Rota from the rampant tourist developments of nearby areas. “Here there hasn’t been that greed because people make good money,” he says. So the streets, which go right up to the shore, seem preserved to give the place the air of a village where Andalusian and American twangs mingle without bothering each other.

For Benítez Reyes, the relationship between Rota and the base is “the normalization of the anomaly.” In his novel, El azar y viceversa (or, Chance and vice versa), this universe is described as if it were a film by Spanish director Luis García Berlanga. Now there is no longer the invasion of bars and other distractions, but Rota is marked by the novelties that made children (and adults) feel like they were living in another world of pure Americana. There were chewing gum and records, the hairstyles and the music of the era, and even Cadillacs. Now that time has passed, there are still symbols that make Rota identical to what it was like when Franco issued his decree.

“Rota was divided by then by two parallel arteries, Calvario street and San Fernando Avenue,” explains Benítez Reyes. The Rota natives from the countryside lived on Calvario street, while San Fernando Avenue was “the alternative American universe, with the American bars, the pizza and hamburger joints, the laundromats, and even patrols that the townspeople called the chopatró, which was their [phonetic] translation of Shore Patrol. The military authorities used these patrols to control the rampage of soldiers on leave.” Those patrols ended when Franco died in 1975.

When the US Sixth Fleet docked there, more than 1,000 people disembarked into the town, joining the 3,000 who already lived on the base and its surroundings, “receiving overseas salaries in a country well below the value of the dollar, so Rota was a big party,” Benítez Reyes notes. Now the soldiers on leave stroll up and down eating ice cream in the streets, and will no longer find the signs in English advertising bars and other attractions while little donkeys carry sand for concrete along the avenues.

“Leaving aside geopolitical issues, this town benefited from the military installation,” says Benítez Reyes. “Rota had few resources. Tourism was limited to a few families and in general, people lived off fishing, agriculture and small business. There was no powerful bourgeoisie. The agreement in 1953 to build the base set in motion very accelerated economic progress that gave way to a kind of spontaneous cosmopolitanism. People of all different races came here and new customs were established.”

People like Benítez Reyes heard new music in their adolescence, and for the Americans they could feel almost like at home, “not in a strange country, but one in which they could live as if they had never left Nebraska, for example,” he says. Before the facilities became used jointly by Spanish and US forces, “entering the base was like entering a North American town,” the writer recalls. Globalization changed everything and Rota is, like the rest of the world, somewhere you can pick up a hamburger easily.

The graffiti slogans of the eighties, like “NATO no, bases out,” persist in the surroundings of the base. “You may not agree with them [the military], but on the other hand you know that the closure would affect thousands of people for the worse,” says Benítez Reyes. “For many, it is almost a religion: they went from having no future to having a good one.” Those in the know say that the hypothetical closure of these facilities would also be “the end of an industry.” And what an industry.

Susana Reiné, a first mate, has been serving on the Spanish section of the base for 16 years. She notes that there is “a very good relationship between the people of Rota and the American side, and there have always been Americans who stay on to live there.” Two years ago it was rumored that the Americans were going to Morocco “and people were pulling their hair out!”

Manuel Perez Garcia, a colonel from the Spanish region of Asturias, who is the head Navy press officer at Rota, has been in the town for 30 years. He stayed to live in an apartment that an American rented out to him and he observes that foreigners now go “unnoticed in the Rota of today.” He says he will stay in the town forever. “This isn’t like those tourist towns on the coast, with that air of artificiality, like an international village. There has been proper urban planning [in Rota].” At the base, there is a wood that appears to have been transplanted from England, but is in fact pure raw material from the woods of Rota.

If the base disappears, “the town would go down in the stock market, it would collapse!” says Javier Ruiz Arana, of the Socialist Party (PSOE), who is the mayor of Rota. Firefighters on the base, when there are fires, are from Rota. The direct and indirect jobs generated by the base, including rental income and service-related activities, mean that Rota would not be what it is today without it, says Arana. “It would be a different town,” he explains. “This place has changed with the world at the pace of global reality, and that has not happened at other bases, perhaps because of the proximity here, the character. In the 1950s, a small town in a Spain under a dictatorship, with many economic and social problems, rubbed shoulders with the culture of a first world power. That was a major shock and Rota has emerged unscathed.”

The Spanish admiral in charge of the base, Ricardo A. Hernández López, and the US commander Daniel Baird are still sharing this peaceful coexistence today. Even the protests are becoming rarer and rarer. These military men say they are there to preserve world peace, and it would seem that on a September day when the Afghans rescued by the United States are about to leave the base for the hopes of another future, Rota continues its role as “the normalization of an anomaly.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.