Corinna Larsen planned for 30% of income from a Spanish-Saudi fund to be bequeathed to former Spanish king Juan Carlos I

The Pandora Papers reveal that the German consultant called on the managers of a trust to send part of the income from this vehicle to the then-monarch in the case of her death

Corinna Larsen, who was at one time in a relationship with Spain’s emeritus king, Juan Carlos I, made plans in 2007 to call on the managers in New Zealand of a trust called Peregrine to bequeath income from an investment fund to the former monarch in the case of her death. According to the unsigned documents seen by EL PAÍS, the plan was for “30% of the income originating from the Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund,” which the former head of state had sponsored and for which Larsen had worked, to be handed over. The papers were created on March 27, 2007, 14 days before the fund created by the two countries was registered in the Channel Islands, which are a tax haven. Larsen’s lawyer claims that the documents are fake.

The details of the structure of this arrangement form part of the Pandora Papers, a collaborative investigation by several international media outlets coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Over the course of two years, more than 600 journalists from 117 countries have analyzed 11.9 million files from 14 law firms specialized in creating offshore companies in tax havens. These types of offshore companies are legal as long as the owner declares them in their country of residence. The problem begins, in the eyes of the authorities, when what they seek is anonymity and tax evasion. In Spain, EL PAÍS and La Sexta television network have sought out individuals in the public eye who have taken advantage of the most opaque jurisdictions in the world. The result is more than 700 companies linked to Spain, including dozens of high-profile personalities.

The financial instrument such as the aforementioned Peregrine, a trust or trust fund, is a particularly opaque contract by which a testator leaves their entire estate of parts thereof entrusted to the good faith of their legal representative (the trustee) so that, in determinate cases and timeframes, it is transferred to another person (the beneficiary) or invested according to the instructions laid out by the testator. Trust funds are commonly used instruments offered by Swiss banks and asset managers to people in possession of significant wealth who are looking for tax avoidance, security and confidentiality.

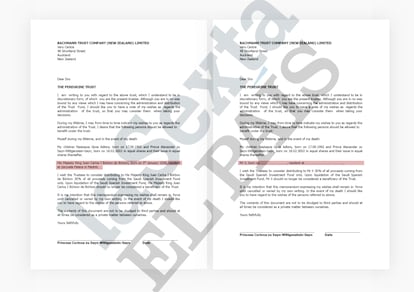

From the documentation it is understood that in 2007 Corinna Larsen called on the Panamanian law firm Alcogal to send a letter to Bachmann Trust Company (New Zealand) Limited, the trustees in charge of managing her Peregrine Trust, and which listed Juan Carlos I among the people who should receive the assets included in this financial instrument in the case of Larsen’s death.

As stated in the letter, which is unsigned, Larsen expressed her wish that in the event of her death the assets in the Peregrine Trust should be distributed “in equal parts” among her two children: Nastassia Gioia Adkins, and “prince” Alexander zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn. Among the beneficiaries, Larsen went on to add “His Majesty King Juan Carlos I Borbón de Borbón, born January 5, 1938 and residing at the Zarzuela Palace of Madrid.” The letter then laid out the assets the king should be entitled to. “It is my wish that the trustees see fit to distribute to His Majesty King Juan Carlos I Borbón de Borbón 30% of all income derived solely from the Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund. Following the liquidation of the Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund, His Majesty King Juan Carlos I Borbón de Borbón should no longer be considered a beneficiary of the trust.”

The document, dated in 2007, concludes: “It is my intention that this memorandum expressing my wishes remains in effect until it is cancelled or modified by my own hand. In the case of my death, I would like the wishes of the aforementioned people to be taken into account. The content of this document must not be divulged to third parties and must be considered at all times as a private matter between ourselves. Sincerely.”

It is unknown whether or not this letter is a draft, given that among the files from the Panamanian firm Alcogal there is a near-identical document, created minutes after the first and in which the space where Juan Carlos I’s name appears is left blank and instead there is a reference to a “Mister X.” It is unknown which formula was actually used, in the case that the plan went ahead. What the document does state is the apparent desire of Larsen for Juan Carlos I to receive a future part of income from the Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund, income about which the letter does not offer further detail.

The name of Juan Carlos I also appears in Article 18 of the Peregrine Trust’s statutes, alongside those of Larsen’s two children. In this section, dealing with the rights and obligations of the beneficiaries, he is referred to as “His Majesty King Juan Carlos Borbón de Borbón.” On the final sheet of the 21-page document, Larsen writes her name under the stamp “signed and delivered” as “Princess Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein.” This document is also unsigned.

What is the fund that is referred to in this document and that could apparently have provided Larsen with income that would have partially been transferred to Juan Carlos I in the case of her death? In 2007 Larsen, a German-born Danish businesswoman and consultant and former spouse of German aristocrat Prince Casimir zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn, was an active participant in the founding of the so-called Spanish-Saudi Infrastructure Fund (Fondo de Infraestructuras Hispano-Saudí), which was announced in April 2006 in Riyadh during an official visit by the Spanish monarchs, Juan Carlos I and his wife, the former Queen Sofía, and a group of Spanish business leaders. The fund was jointly managed by the British asset management firm Cheyne Capital and Swiss-based Arox Infrastructure. The former contracted US investment bank Morgan Stanley to attract investors among Spanish lenders and businesses interested in participating in an ambitious and wide-ranging infrastructure project in Saudi Arabia, of which the Mecca AVE link was the most emblematic part.

The idea of creating this fund came from then-Foreign Minister Miguel Ángel Moratinos, and from Juan Carlos I himself, according to sources close to the former minister and the emeritus king. “We needed to strengthen the relationship between Spain and Saudi Arabia; our investments there were very small and we already had large corporations here,” says a former minister in the Socialist Party government of then-Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, who was involved in setting up the fund. “The king said, ‘We have to do something.’ And we decided to create a fund for the two countries that would guarantee future investments. It was a huge opportunity and the Saudis were to represent the majority share. It was a joint initiative between the Foreign Ministry, the Royal Household and the Industry Ministry.”

On June 14, 2007, the late Saudi monarch Abdullah bin Abdulaziz visited Madrid for the first time and was styled a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece by Juan Carlos I, the insignia of a 15th-century chivalric order and the highest decoration awarded by the Spanish Royal Household. During that encounter, the Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund was officially unveiled with 14 Spanish companies signing up to the accord in its initial phase. Also present at the ceremony was Corinna Larsen, who was unfamiliar to the wider public at the time because her romantic relationship with the then-head of state had not yet come to light.

The Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund had planned investments worth €4.125 billion to carry out joint projects between the two countries in infrastructure, new technologies, industry, energy and defense in Saudi Arabia, the Middle East and North Africa. Some 14 Spanish companies agreed to invest in the fund. Saudi Arabia did not make the contributions that were expected and as a result the fund was eventually dissolved. “The Saudis let us down. They put a man in charge who was not up to the task. When the required amount was not reached, it folded,” recalls the former government minister involved in launching the fund.

The Spanish-Saudi Investment Fund was dissolved in 2010 and its managers sent bills for their services and expenses to the large companies of the Spanish Ibex 35 stock exchange who had signed up to participate in the project, according to former executives who were involved in the investment deal. A year after the creation of the fund, the Saudi Ministry of Finance transferred $100 million (€65 million according to the exchange rate at the time) to an account belonging to Panamanian foundation Lucum, held at Swiss bank Mirabaud & Cie and whose main beneficiary was Juan Carlos I.

The order for the transaction was given by then-king Abdullah bin Abdulaziz and according to the manager of the account, Arturo Fasana, was presented as a gift or donation. Swiss prosecutor Yves Bertossa has indicted Larsen for alleged money laundering offenses following the discovery of the transfer. Bertossa is also investigating whether this deposit has any connection to the construction of the AVE rail link between Medina and Mecca, a project carried out by a consortium of Spanish companies.

Juan Carlos I is currently under investigation by the Spanish Supreme Court public prosecutor in connection with alleged kickback payments stemming from the construction of an AVE high-speed rail link from Medina to Mecca, and for other alleged offenses including bribery, perverting the course of justice, influence peddling and tax evasion. Javier Sánchez Junco, the emeritus king’s attorney, declined to respond to questions sent by EL PAÍS.

Robin Rathmell, Larsen’s lawyer in London, denies that this plan existed and claims that the documents are fake. “Baseless rumors are circulating that Juan Carlos was a beneficiary of a structure relating to Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein,” he said in a statement. “These rumors originated from falsified documentation. The evidence showing that these documents were fabricated was placed before the Swiss authorities in 2019. This will also be dealt with as part of the harassment case my client is pursuing in England against Juan Carlos.”

A corporate matrix

Bachman Group Ltd, the firm that managed the Peregrine Trust held by Corinna Larsen, is part of a group owned by Geneva-based Ardel Trust Company, which specializes in asset management and setting up trusts and offshore financial structures. In 2013, Ardel Trust Company was acquired by fund management services provider JTC Group.

In the 21-page statute and regulations of the Peregrine Trust, dated in 2007 and containing the rights and obligations of the administrators and trustees of the fund, the names of Bérénice Guignard Nava, on the part of the Bachman Group and who is currently an executive at the Ardel Trust Company in Geneva, and Martin Pugh appear.

The threads of Larsen’s trust fund are difficult to unpick. Ardel Trust Company also managed Peregrine 55, another fund linked to the Peregrine Trust that was dissolved in 2013.

The letter written by Larsen, a consultant by trade, giving instructions for the distribution of assets from the Peregrine Fund, was addressed to the Bachman Trust Company (New Zealand) Limited, in Auckland. Furthermore, Bachman Group Ltd held offices in Guernsey, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.