The downfall of Spain’s Juan Carlos I

The emeritus king has been immersed in scandals since 2012, when he was caught in Botswana on a safari trip to kill elephants

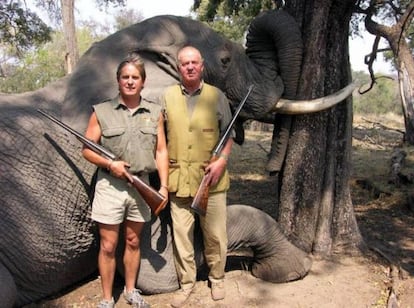

The annus horribilis of the Spanish monarchy began in April 2012 in Botswana, 7,200 kilometers from Zarzuela Palace, Spain’s royal residence. But it lasted much longer than 365 days. Indeed, it hasn’t ended, despite the fact that Spain’s emeritus king, Juan Carlos I, announced on Monday that he would leave Spain to ensure his reputation would not continue to harm his son, King Felipe VI, who became head of state in 2014. Juan Carlos’ trip to Botswana was not his first safari, nor was the woman he was photographed with, Corinna Larsen, his first female friend. But the royal household would soon discover that this trip would mark a “before and after” for the monarchy.

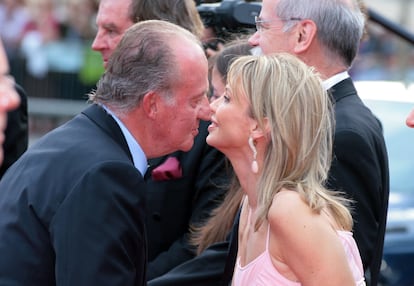

At the time of the trip, the country was about to accept a bailout for its ailing banks and unemployment was skyrocketing. A few days before the safari, Juan Carlos had said that the thought of young people in Spain unable to find work was keeping him up at night. An accident – the king fell and broke his hip – meant that, unlike other occasions, this safari would not escape public notice. Zarzuela Palace considered all options, including concealing what happened, but at 9.30am on April 14, 2012, on the 81st anniversary of Spain’s Second Republic, the royal household reported that Juan Carlos had had an emergency hip operation after having an accident on a safari. The trip to kill elephants, at a cost of more than €40,000, had been paid for by Mohammed Eyad Kayali, an advisor to the Saudi royal family who was named in the 2016 Panama Papers as the head of 15 offshore companies. The king was not alone on his trip: he was with a woman with an exotic name that would soon be learned by the Spanish people: Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein – she went by her ex-husband’s name to present herself as a princess – or Corinna Larsen, her maiden name.

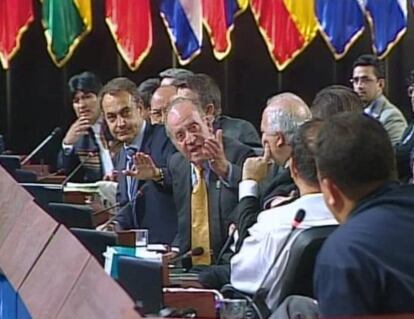

Juan Carlos’ wife, Queen Sofía, waited three days before visiting her husband in the hospital. In the middle of the crisis, the country was furious with the king, who in 2007 had won praise for telling then-Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez: “Why don’t you shut up?” at the Ibero-American Summit in Chile. The phrase was turned into ringtones and printed on t-shirts – Juan Carlos even gifted one to Chávez at the same summit the following year.

Don Juan Carlos discussed the situation with people he trusted. He was worried. He and his team spent hours putting together a speech of two sentences: “I’m very sorry. I have made a mistake and it will not happen again.” Former staff members of the Zarzuela Palace were dismayed – “Kings do not apologize!” – but according to sources from the royal household, the gesture had to be equal to the level of public anger. “It humanized him,” said then-foreign minister José Manuel García-Margallo. It was this minister who the monarch would ask to receive Corinna Larsen, who is now under investigation in Switzerland for money laundering.

The public opinion polls that Zarzuela Palace periodically orders, strictly for internal use, showed a sharp fall in support for Juan Carlos at that point. “All the members of the House of Bourbon have hunted and have had lovers, but Spain was going through a very serious crisis and the new generation of Spaniards did not tolerate what was before tolerated,” explains the French historian Laurence Debray, the author of a biography of the former king, Juan Carlos de España (or Juan Carlos of Spain).

The royal household launched a public campaign to try to restore the king’s reputation, but this sometimes backfired, bringing to light other problems and old mistakes. For example, the accounts of the royal household were published for the first time in the institution’s history, but this acted as a reminder that the personal wealth of the monarch is still not known.

Then Juan Carlos gave up the Fortuna, a €18-million yacht that cost €20,000 just to get started, but this brought up the boat’s history, and the fact that it was a gift bought by 25 businessmen and the Balearic regional government. In her biography of Juan Carlos, Debray explains that the former monarch had a peculiar relationship with money: “He had known as a young man the humiliation of having to economically depend on rich Spanish aristocrats who were voluntarily ensuring the lifestyle of the royal family in exile.” The Spanish royal family was forced into exile following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931. The dictator Francisco Franco overthrew the Second Republic but waited 10 years, until 1947, before declaring Spain a kingdom, and another 22 years before naming Juan Carlos de Borbón as his successor.

By January 2013, several members of the royal family and their team had read a study called Monarchies as Brands, written by three marketing experts who had interviewed the king and queen of Sweden, Princess Victoria and several of their communication advisors. The conclusion was that the institution depends on two pillars of support: the people and the parliament. The disappearance of one is enough to cause its collapse. After the trip to Botswana, the Spanish royal household had begun to lose the initiative: it couldn’t make plans or set objectives, and it spent the next few years reacting to scandals and looking for ways to minimize the damage to the monarchy’s reputation.

In politics, sources from the Popular Party (PP) and the Socialist Party (PSOE) began to accuse one another of being too lenient with the king, of not disapproving more forcefully of his getaways. The Nóos graft case in which Iñaki Urdangarin, Juan Carlos’ son-in-law, was accused of securing no-bid contracts from regional governments using his position in the royal family, and the Botswana safari put a spotlight on the Spanish monarchy, an institution without executive power, whose reason for being and main mission in life is to provide a good image. After Juan Carlos’ fall in Botswana, his son-in-law Urdangarin and daughter Cristina began to be treated like any other public official facing charges. Urdangarin ended up in prison and the mistakes of Juan Carlos, both past and present, were exposed.

Some of the more dangerous friendships of the monarch also came to light: the disgraced Spanish banker Mario Conde, the businessman Javier de La Rosa, and the diplomat Manuel Prado y Colón de Carvajal, all of whom spent time in prison. Other scandals emerged, like the eight million pesetas (€48,000) that the royal household had paid to avoid the publication of love letters that a very young Juan Carlos had written to Countess Olghnia de Robilant, and his subsequent relationship with the Spanish socialite Marta Gayá.

In the private opinion polls as well as the social media analysis that the royal household ordered, there was only one conclusion: there was no more room for error. In a bid to save the image of the institution, Juan Carlos, who had once said that “kings die, they do not abdicate,” ceded the throne to his son. The generation that did not live through the 1981 coup attempt, which came to an end when Juan Carlos appeared on television in full military uniform to denounce the plotters, was mostly more in favor of a Spanish republic than the monarchy, according to a survey published by Metroscopia before the proclamation of Felipe VI as king in 2014. Debray interviewed Juan Carlos a few days before he announced his abdication: “I don’t like power,” he told her. The historian concluded that he believed “that he had fulfilled [his role].”

But the spotlight remained on the monarchy. It was revealed that Juan Carlos had transferred €65 million to Corinna Larsen, that he had bank accounts in Switzerland, and that a foundation in Panama had named Felipe VI as a beneficiary. This final revelation prompted Felipe VI to renounce the inheritance from his father and strip Juan Carlos of his yearly stipend of nearly €200,000.

“If the king had died before the infamous elephant hunting trip, he would have died a hero, the man of the miraculous transition to democracy, the symbol of the modernization of Spain,” says Debray, who as a child had a poster of Juan Carlos in her room. “I believe that nobody was expecting such a sad end, in which only corruption and lovers are being talked about and his political work is being forgotten. It’s complete disappointment. The tragic end to a sad fate: to be born in exile, to grow up in a strict boarding school in Switzerland, to lose a brother, to live in Spain while depending on your father’s enemy, Franco…”

As Viscount Bolingbroke wrote in the 18th century: “Just as kings must never forget they are men; men must never forget that they are kings.”

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.