‘I am here to support you’: Violetta, Sophia and Sara, the chatbots that assist victims of gender violence

Projects in different countries explore how artificial intelligence can guide women who experience gender-based violence, in addition to collecting information about this problem

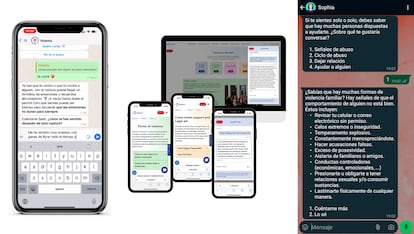

Everyone can talk to Violetta. With just one message via WhatsApp, the chatbot quickly replies: “I’m here to give you the tools you need to create violence-free relationships.” Even though Violetta cannot be seen or touched, the chatbot has supported 260,000 anonymous users in Mexico over the past year. Violetta is one of several projects using artificial intelligence (AI) that have been created to address gender-based violence, a structural problem that affects one in three women in the world. Tens of thousands of users have turned to technology to seek help. This is because shame, fear of being judged and not having a family environment that can offer support in the reporting process are all factors that prevent many women from taking the first step to escape the cycle of violence in which they are immersed.

“More than a chatbot, I am your digital confidant,” says Violetta, which was launched in Mexico by Floretta Mayerson, Sara Kalach, Sasha Glatt and Carla Pilgram during the Covid-19 lockdown. At the time, the telephone lines offering support for those suffering from gender-based violence were overflowing. Hundreds of homes ceased to be safe spaces, in a country that sees more than 3,000 women murdered each year.

Macarena Estefan, the director of Psychology at the firm Violetta, explains that the objective of the chatbot is to be a bridge “that facilitates the listening process.” The founders realized that many people turned to search engines such as Google to resolve their doubts, even before venting to a human. “A victim can take from one to five years to speak,” she emphasizes.

Violetta is the first machine learning model in Spanish. It’s a supervised and non-generative AI (like ChatGPT), which is based on a dataset and uses specific algorithms. The app draws users — more than 70% of whom are young and adult women — who are experiencing extreme situations to the “Purple Line,” which is staffed exclusively by a team of therapists. Since the pandemic, the chatbot has managed to direct 40,000 people to specialists, although it also offers contact information for legal organizations.

Meanwhile, Sophia Chat — the chatbot created by Spring ACT, a Swiss NGO — also emerged during the pandemic and has helped more than 40,000 victims of violence since its launch. Founder and CEO Rhiana Spring works with a team of social workers, psychologists, programmers and lawyers, who have all trained Sophia. “We started [working on] Sophia three years before ChatGPT became a global phenomenon. There are many important differences, since it doesn’t ask you to log in and the bot’s information is [very] accurate. We work with a verified database,” she explains.

In 2022, Sophia was launched in Peru, due to the Andean country’s high rates of gender violence: more than half of Peruvian women and girls have experienced some type of physical and psychological aggression. The chatbot is able to communicate in Spanish, as well as in Quechua, the largest Indigenous language in Peru: “Hello! Could you give me more details on how I can help you today? I am here to offer information and support.” Sophia’s database includes institutions such as the Women’s Emergency Center (CEM), the National Police of Peru and other services.

The virtual assistant Sara was launched in the Dominican Republic in 2023 to help women, girls and adolescents who are victims of gender-based violence. A year later, the chatbot María appeared in Honduras. In both countries — with the highest rates of femicide per capita in Latin America — the Spain-based start-up 1MillionBot developed these chatbots to adapt them to local contexts. This was done in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Sara has directed more than 3,000 users to public institutions and Dominican women’s shelters. Raquel Pomares, production director of the start-up that coordinates Sara and María, says that the team is focused on improving the quality of information surrounding gender-based violence: “We think it’s a powerful tool… the educational [capabilities] that the chatbot has are undeniable.”

Macarena Estefan stresses that chatbots are great digital tools, “but in other cases, it’s very important that people speak with a professional. We know the limitations that this technology has.” It is worth noting Violetta, Sophia, Sara and María don’t cross-reference users’ information, so as to maintain anonymity. They can be used on a computer, or on a mobile phone via WhatsApp and Telegram.

AinoAid will soon be available in Spain

The Local Police of Valencia (PLV), in Spain, is currently perfecting AinoAid. This chatbot was created in Finland in 2021 within the framework of the Improve project, which receives funds from the European Union. AinoAid™ is currently in the testing process, absorbing information and, above all, practicing interactions with human beings. Inspector José Luis Diego — who works in the Innovation and Research department of the PLV — admits that quite a lot of work has been involved in this. “We’re in the process of translation, we need the tool to be 100% accessible,” the officer emphasizes.

The team is in the most complex phase of development, which will culminate with the presentation of a first prototype in November of this year. In Spain, the number of women victims of gender violence increased by 12.1% in 2023, according to figures from the National Institute of Statistics.

Anna Juusela is the CEO of WeEncourage, one of the partners of the project that originally developed AinoAid, which currently assists 600 users per month. “Victims need support and it’s not possible to help them from a single front. The chatbot doesn’t replace humans, because we need professionals from the health sector to the police sector,” she reflects.

This digital tool — which will be available in five countries, including Germany and Austria, by the end of 2024 — is focused on providing professionals (such as police officers trained in these matters) with knowledge about how to improve their response. In this regard, Joachim Kersten, one of the coordinators of Improve, believes that officers “find it difficult to address gender-based violence because they are generally not qualified to do so.”

The Innovation department has been advised by the Gender Unit of the PLV, which has more than 700 women under its protection. Estefanía Navarrete, the coordinator of the Abuse Care Group (GAMA), remembers that, during the pandemic, they detected many cases of women who were trapped under lockdown with their aggressors. This situation made them start to consider other ways of communicating to seek help.

“The first thing I thought about when I heard about the chatbot is all the women we can’t contact, [those] who don’t dare to tell a police officer at a police station what’s happening to them. The chatbot can guide them to take those first steps,” she says.

“Abusers [attempt] to remove any escape route. Many women have children [with their abusers] and the idea is to provide them with bridges,” she explains. Diego, from the PLV, believes that the bot will help to identify cases as early as possible, before the aggression gets out of hand. “We’ll be able to detect this hidden figure and thus improve our police response,” he affirms.

AI in gender-based violence complaints

The Gender Data Observatory in Argentina developed AymurAI, an AI system intended to review court rulings on gender-based violence. Ivana Feldfeber, director of the project, says that the main idea is to collect anonymous information, so as to better understand how justice operates in these cases. “We were interested in understanding what was happening in the judicial powers, because we know that there are many women who report [abuse], go to trial… and then the case comes to nothing,” she sighs. AymurAI reviews court rulings, extracting valuable information about the management of these cases, the decisions that are taken and the protective measures put in place for the victims. To date, the software has analyzed 10,000 rulings.

For Feldeber, the lack of transparency in the judicial treatment of gender-based violence translates into low levels of reporting and distrust in the courts. “We know that it’s difficult to report and the women who do so are able to because they also have a support network and there are witnesses who can testify in their favor,” she stresses. AymurAI collaborates with Criminal Court No. 10 of the city of Buenos Aires and will soon be launched in Mexico.

“Many women are denied requests for precautionary measures, preventive detention, or alimony. Many judges decide not to grant these requests and rule in a very sexist way against women,” Feldeber sums up.

The project receives international funding and is part of the Feminist AI Research Network (FAIR), a global network of scientists, economists and activists whose purpose is to make AI and related technologies inclusive and transformative. And there are other similar initiatives, such as the Chilean chatbot SOF+IA, or apps that specifically deal with sexual harassment in public transport, like SafeHER, designed in the Philippines.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.