The napkin deal that brought Messi to Barça drives auction for thousands of dollars

The iconic document that FC Barcelona used to convince the father of the Argentine star is being auctioned off, with the starting price at $350,000. The agent Horacio Gaggioli previously offered the serviette to the club, but it chose not to buy it

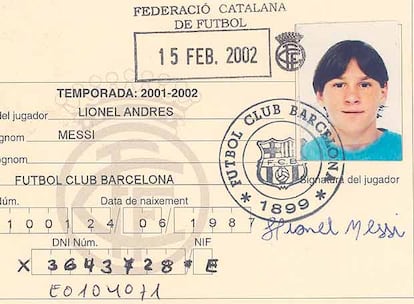

FC Barcelona’s budget in the 2001-2002 season — Lionel Messi’s first at the club — was 25,660 million pesetas (€154 million, $167 million). This season, club president Joan Laporta expects Barça to make €854 million ($927 million), although it was in the 2022-2023 season, when it underwent a financial restructuring, that it posted record profit: €1.26 billion ($1.37 billion). In other words, in the 22 years since Messi joined the soccer club, Barça’s profit has risen by €800 million ($869 million).

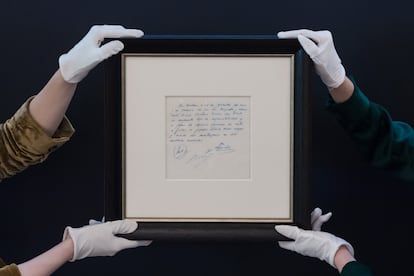

“It was another era, another kind of football,” remembers Antón Parera, who was general director of the team, first during the presidency of Josep Maria Núñez and later under Joan Gaspart. “Everything was…” adds Parera, before taking a few seconds to reflect; “more normal.” Normality, in this case, wrapped in romanticism and legend: Barcelona (supposedly) sealed the deal to sign its most important player ever, Leo Messi (672 goals and 35 titles, including four Champions League titles), inside the bar of a tennis club and with a verbal contract. That agreement was recorded on a napkin signed by Carles Rexach, the club’s sporting director, and the agents Josep Maria Minguella and Horacio Gaggioli. The napkin, a treasure kept in different safes, was put up for auction by Bonhams in London, with a starting price of €350,000 (380,000). The auction ends on Friday.

In 2000, when Argentina was headed for the worst economic crisis in its history (the financial and social situation led to the 2001 corralito, the informal name for the measures taken to stop a bank run, such as a limit on cash withdrawals), the Messi family was contemplating moving to Australia. Jorge Messi, the head of personnel at a company in Rosario, was looking for a better future for his four children: Rodrigo, Matías, Lionel and Marisol. It was at that point that the possibility of moving to Barcelona arose, with the club saying it might be willing to pay for Lionel’s treatment to address his growth hormone problem and to help the entire family.

“The day we left Argentina we had a bag full of dreams and hopes, but also many fears. Lionel seemed to enjoy that trip. Surely, in his head he was only thinking about the idea of getting to know, arriving and staying in Barcelona. But I suppose he was also beginning to forge the idea of succeeding in what he wanted most: soccer,” Jorge wrote after Leo won his fifth Ballon d’Or.

But his plans of success were met with some setbacks. The first was the wait. And that’s where the napkin comes into play. “Messi?” Rexach remembers; “I signed him in five seconds. Seeing how he stopped the first ball he touched was enough to convince me.” However, after Messi passed the trial in September 2000, Barcelona delayed getting back to the Messis, who had returned to Rosario and were waiting for confirmation.

“We were talking about a little boy who played soccer very well. At that time, nobody knew that Messi was going to be Messi. And it was an important bet for the club,” explains Parera. That was when Rexach — who knew that they could not let the Argentine star get away from them — met with Gaggioli and Minguella at the Pompeia tennis club. “Charly [Gaggioli] had probably met there to play tennis with Minguella,” says Parera. It was that day, January 14, 2000, when the agents and Barcelona’s sporting director tried to reassure Jorge Messi.

How did they calm his concerns? With a contract signed on a napkin: “In Barcelona, on December 14, 2000, and in the presence of Messrs Minguella and Horacio, Carles Rexach, FC Barcelona’s sporting director, hereby agrees, under his responsibility and regardless of any dissenting opinions, to sign the player Lionel Messi, provided that we keep to the amounts agreed upon.”

The contract’s legal validity? None. Was it trusted? Absolutely. At least, that’s what it seemed. “There were no people who charged commissions, nor so many advertising companies. It was normal at that time,” says Parera. Gaggioli was in charge of safeguarding the napkin and, with it, the beginning of its legend. A story that would have died without the presence of Juan Lacueva, who was managing director of Barcelona at the time. “Without Juancito, Messi today would not be Messi. Sorry, that’s my opinion,” says Parera.

“The story about the napkin is a very beautiful story, very romantic, but it lasted one day,” says Marc Lacueva, the son of the late managing director, who is an agent for soccer players. Jorge Messi, incredulous about the napkin deal and with no clear resolution to the conflict over his son’s contract, spoke with Barcelona. And that’s when Lacueva took action. “Leo’s first contract is only signed by my father, as manager of the club. He got into big trouble for doing that. They told him, ‘do you think this is Espanyol?’, remembering his past in the other club,” says Marc Lacueva.

But Juan Lacueva’s efforts did not end there. As Messi needed to undergo his hormonal treatment and the club continued to be trapped in bureaucracy, Lacueva paid for Lionel’s first Human Growth Hormone injections out of his own pocket.

“What manager today pays for treatment out of their own pocket?” asks Parera. “I remember a discussion with Lacueva. [He said] ‘When this boy succeeds, we will be gone and no one will thank us.’” Indeed, few talk about Lacueva: all interest is centered on a napkin that Jorge Messi never signed.

“The only documented owner of that napkin is me,” Gaggioli said in an interview with Diario Olé, after Minguella threatened to file a lawsuit in March that prevented the auction from taking place last March. “[The napkin] should be in the Barça museum, in a preferential place next to Messi’s Ballon d’Or trophies, since that little piece of paper is what changed the modern history of the club,” he insisted.

“It is true that Horacio [Gaggioli] offered the napkin to the club,” say sources from FC Barcelona. So why isn’t it in the museum? “He asked for money, an amount that depended on the number of museum visitors,” added the sources. The napkin was initially kept in a safe deposit box in a Caixa bank office in Barcelona before being moved to the Bank of Andorra. And, given 22 years have passed since the napkin deal was drawn up, today money does matter.

Messi, for his part, doesn’t want to know anything about the napkin. In fact, Jorge Messi never saw the document signed by Rexach, Gaggioli and Minguella. “I never sent the napkin to Rosario, because it didn’t make sense. It was simply a way to unblock the situation,” said Gaggioli. But the legend surrounding the napkin deal remains alive: from the past to the present, from the romanticism of a verbal contract to an auction at the London headquarters of Bonhams.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.