Historic mountain hut falls from its Alpine perch

The Bivouac de la Fourche on the Italian side of Mont Blanc was the starting point for a 1961 climb that ended in tragedy

We know that the seasons radically affect mountain conditions and how climbers should approach climbing them. When viewed from afar, a mountain can seem immovable and immutable, but up close it is full of life and motion. What we didn’t expect was how the summer of 2022 heatwave in Europe would change the face of Alpine mountaineering.

Men and women have climbed and descended mountain peaks for centuries, ephemeral figures, in search of things hidden in places not meant for humans. But now the Alps – the cradle of mountaineering – are changing. Trails are being erased, ice field traverses are disappearing, summit routes are no longer viable and mountain refuges are collapsing. Three of the legendary Mont Blanc landmarks associated with pioneering alpinist Walter Bonatti no longer exist: the southwest rock pillar of the Dru; the Charpoua refuge above Chamonix (France) from which Bonatti set out in 1955 on his solo ascent to the summit; and now, the Bivouac de la Fourche.

There were many warnings, but none as symbolically charged as the frightening collapse in 2005 of the pillar of the Dru, an imposing column of rock also called the Bonatti pillar. The route on which the Italian guide spent five nights trying to reach the summit, was totally washed away by a series of huge rock falls, leaving behind a dense curtain of dust and nine million cubic feet (260,000 cubic meters) of rock scattered everywhere.

Some melodramatic observers saw the pillar’s collapse as a kind of suicide – a proud rock that didn’t want to witness the unfolding disaster. The Charpoua shelter was beginning to crumble and was reverently dismantled earlier this summer for reconstruction. Bonatti once wrote that after leaving the shelter, he slammed its wooden door shut, so he wouldn’t be tempted to go back inside, gather his belongings and flee the mountain without facing the Dru.

There have been other huge rockfalls in the Alps this summer – on the traditional route up Mont Blanc, on the Lyon ridge of the Matterhorn (France), on the Tour Ronde mountain (on the border between France and Italy), and on the Cosmiques ridge (Mont Blanc massif). Then, on August 26, the tiny Fourche hut fell from its perch and shattered on the glacier almost 1,000 feet (300 meters) below.

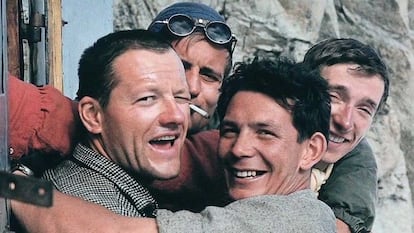

The Fourche hut was built on the Kuffner ridge of Mont Maudit, a mountain in the Mont Blanc massif in France and Italy, which is the starting point for Mont Blanc’s Brenva slope. The hut was also associated with what is known as the great tragedy of the Central Pillar of Frêney. Located at 12,000 feet (3,675 meters), on the border between France and Italy, the structure was built in 1935 and completely renovated 50 years later. On July 8, 1961, four friends and mountain climbers from France – Pierre Mazeaud, Robert Guillaume, Antoine Veille and Pierre Kohlmann – took a snapshot at the hut before setting out on their climb. Days later, only Pierre Mazeaud was still alive.

On July 9, 1961, the four Frenchmen were already at the Bivouac de la Fourche when Walter Bonatti and two friends, Andrea Oggioni and Roberto Gallieni, arrive. All were intending to climb the same route: the Frêney central pillar, a huge column with almost 200 feet (60 meters) of sheer rock face. It was the last great Alpine challenge and the toughest Mont Blanc ascent route. Bonatti asks the French climbers if they would like to go first. No way, they say.

So they decided to join forces and form a single rope line. After spending a night on the wall, they reached the site of their second bivouac right before a major storm pummeled half of France for days. That same evening, lightning strikes Kohlmann through his earphones. He is alive, but unconscious. Five days after starting their adventure, in the middle of a fierce snow blizzard, they give up hope of making it to the top. Bonatti, who knows what it’s like to face an angry mountain, organizes the descent, which turns into carnage.

The Italian rallies his companions, sets up the rappels, and forces them to fight despite the danger, frostbite, thirst and hunger. Antoine Veille, the youngest at only 22, died at dawn on July 15, exhausted. Robert Guillaume passes away a few hours later. Kohlmann is still alive, but becomes delirious and attacks Gallieni, who has no choice but to leave with Bonatti in search of help at the Gamba refuge. The rescuers only find Mazeaud still alive. Oggioni, Bonatti’s great friend, has fallen asleep and will not wake up. Kohlmann was already dead when he was struck by lightning, but death waited five days to take him.

The French and Italian media pounced on the tragedy with characteristic sensationalism and wanted someone to blame. It was not enough to mourn the dead. Bonatti was faulted for having survived, despite saving Gallieni and Mazeaud. Oggioni’s family barred Bonatti from attending his friend’s funeral. Four years later, barely 35 years old, Bonatti would say quit mountaineering for good, still in love with the mountains but appalled by the human condition.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.