Operation Save the Celebrities: The inner workings of the therapists who help stars lead a ‘normal’ life

The tragic death of Liam Payne, who had previously sought help to cope with life in the spotlight, brings new life to the debate over whether early, unbridled fame is compatible with emotional stability

It’s undeniably rough to have sipped from the cup of fame at an early age, only to wind up excluded from the A-list. The process of restoring a celebrity’s damaged psyche can be traumatic, its outcome uncertain.

Over the last few days, a media circus has surrounded the death of former One Direction singer Liam Payne, who seemingly became the victim of a breakneck rise to fame at just 17 years of age that gave way to an erratic trajectory as a young adult mourning the loss of his heartthrob status. (His solo career, despite its many victories, was always seen as the least successful among the former members of his superstar boy band.) Some have baselessly reproached the man for not falling back on professional help, but the truth is that Payne, despite his tendency to suffer in silence that many mourners have noted, did try to find backup.

In 2023, the performer spent over 100 days as a patient at a luxury rehab in New Orleans, and in July 2024 checked into a similar establishment, this time outside of London, though he only stayed there for two nights. At any rate, it cannot be disputed that he put himself into the hands of a highly reputable squadron of VIP therapists, professionals skilled in the mending and patching of celebrity psyches.

We heal the famous

A representative from a New York clinic that specializes in services of this kind explains that treatment for the type of psychological problems suffered by celebrities is both similar to and quite different from that which mere mortals receive.

In the opinion of these professionals, the cognitive-behavioral and dialectical-behavioral therapies they offer can be effective with all types of patients, famous or not. But the treatment of any popular performer or Hollywood star must take into account the factors that make them unique, such as their “lifestyle based on continuous and frenetic activity,” a lack of intimacy in everyday situations, a high degree of media exposure, the intense scrutiny to which their private lives are subjected (including, but not limited to romantic relationships), the emotional problems that can be generated by widespread criticism and negative comments, and “the lack of time available for personal growth and enrichment.”

Of course, therapists with a VIP client roster aren’t just treating problems related to fame or with its sudden loss. Among their success stories that have made their way to headlines in recent years is that of supermodel Chrissy Teigen, who turned to a psychologist to overcome acute post-partum depression. Here too is the tale of Lena Dunham, who paid “a fortune” to various professionals for them to teach her to be “a little less cruel” with herself, and that of Prince Harry who, quite simply, needed someone outside his circle with whom he could speak without fear of their conversations winding up on the cover of British tabloids.

Another example can be found in the case of Emma Stone, who began to attend therapy at just seven years old to deal with paralyzing anxiety. It was thanks to psychoanalysis that Jennifer Aniston learned that happiness is not the result of winning the genetic lottery, but rather, “an option, and many times all it takes is choosing it.” Brooke Shields found that anti-depressants like Paxil could help her to restore an equilibrium that she had given up for lost. Kesha put her musical career on hold to dedicate herself to getting the psychological help she needed and had rejected since her teens. Jennifer Garner overcame a painful divorce after a period of attending sessions twice a week. Kristen Bell discovered that there is no need to be ashamed of going to therapy, just as “it’s not shameful to go to the gym if you’re in terrible shape or sign up for cooking classes if you’re not able to bake a cake.”

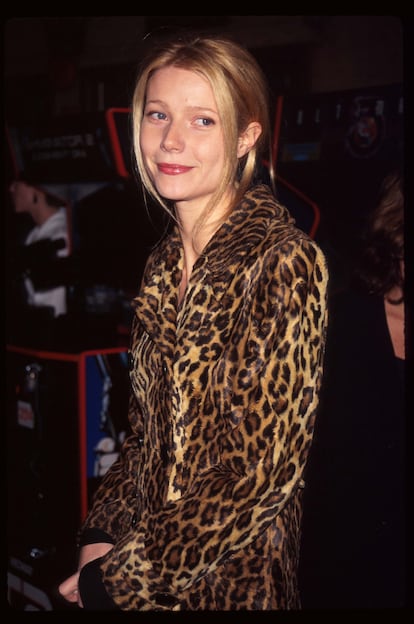

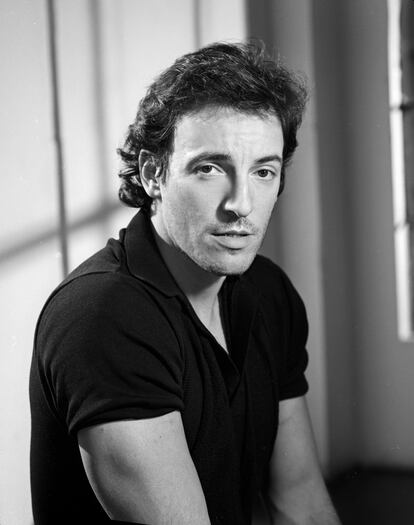

Demi Lovato, Halle Berry, Gwyneth Paltrow, Glenn Close, Selena Gomez, Ariana Grande, Jon Hamm, Kerry Washington and Brad Pitt have all gone to therapy as well, turning to it when they felt as though their lives had started to take them in an unfortunate direction. Even Bruce Springsteen, whose manager and co-producer Jon Landau has described as one of the most sensible, balanced people on the planet, began to attend therapy at the beginning of the 1980s and still returns on a regular basis to his trusted mental health professional.

I love you, Phil

But perhaps the most paradigmatic case of celebs on the couch is that of L.A. actor Jonah Hill, who truly loves his veteran therapist, Phil Stutz. So much so, that Hill even made a documentary about Stutz that premiered on Netflix two years ago. In it, the movie star and psychoanalyst speak calmly about the weight of fame, depression, emotional scars, trauma, labyrinths and therapy. Stutz, in the words of Los Angeles Times columnist Charles McNulty, who wrote a memorable article about the health professional, is a rare example of an intellectual who allows himself to be guided by intuition. He’s unconcerned if this intuition leads him towards violating the most elemental principles of psychological therapy, as interpreted by Freud and his contemporary disciples.

Stutz doesn’t listen to his patients in inquisitive silence. He interrupts them with irreverent humor, tells them of his own experiences, “squawks, curses and blasphemes in his unmistakable New York accent,” stringing together puerile jokes and even wacky provocations (“Jonah, I made out with your mom”) with the intention of forcing an intense emotional connection with his clients. Look not for scrupulous therapeutic distance between the observer and the observed, as prescribed by conventional therapies.

But this is not a man dedicated to a simple, iconoclastic hooligan’s deconstruction of the rituals of the couch. Stutz, as even his critics admit, is a serious professional. There’s a method to his (apparent) madness. That is made clear in The Tools, an introductory book written in collaboration with one of his students who has since become another specialist in providing therapy to the Hollywood stars, Barry Michels.

In The Tools, Michels and Stutz explain the (supposed) virtues of destroying the barrier between patient and therapist, as well as their quite controversial “visualizations” technique. The latter consists of the systematic use of a series of “visual therapy tools” (“the life force pyramid”, “the labyrinth”), which serve as metaphors for the psychological processes the patient is facing. Through them, Stutz helps patients to understand and confront their traumas, reducing them to a series of “intuitive and concrete” coordinates.

Some psychologists question the scientific foundation of this methodology, but that doesn’t stop them from recognizing in Stutz a notable capacity for establishing healing emotional ties with those who come to his office. In the Netflix documentary, Hill winds up defining Stutz as a particularly wise and empathetic “friend” who has taught him to reconcile with himself. In one particularly moving movement, the therapist (who was 75 years old at the time) takes a pill for his Parkinson’s and bluntly declares that he feels true friendship and genuine love for Hill, and that he knows those feelings are reciprocal. His words make Hill emotional.

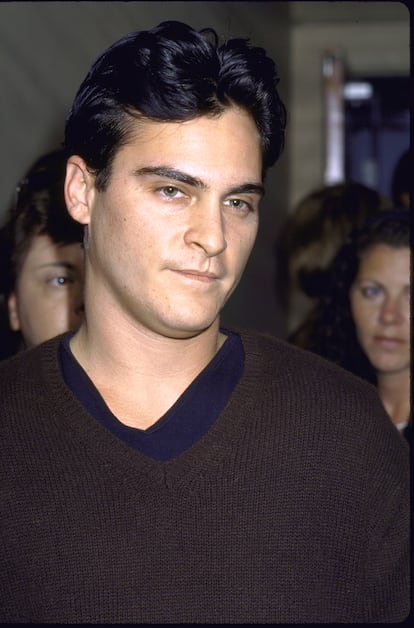

The relationship that Michels has established with one of his best-known patients, Joaquin Phoenix, appears to have taken on similar depth. Phoenix turned to Michels for help in preparing for his role as a nihilist sociopath in Joker (2019), as well as to free himself from the dark thoughts that had inspired him to immerse himself in such a bleak role to begin with. Skeptics tend to think that the “trick” of VIP therapists like Michel and Stutz mainly consists in bypassing therapeutic conventions to establish a personal connection that makes their singer and actor clients feel special. In other words, an elaborate formula for sucking up to them. Stutz has defended himself against such accusations, saying, “I have only one method: the one I use with all my patients, whether they are famous or not.”

Michels and Stutz may be somewhat atypical cases. The primary characteristic of a true celebrity therapist, according to clients like Gwyneth Paltrow, is secrecy. In theory, these elite professionals offer their services in absolute confidentiality. As such, they maintain a low profile, allowing their fame to precede them in elite circles, their name passed from celebrity to celebrity. If someone explicitly offers their services as a therapist to the stars, it’s likely that they aspire to be one, but that they definitively, are not.

That being said, for every conceivable human activity, there is a corresponding reality show — and celebrity therapy is no exception to the rule. Doctor Siri Sat Nam Singh is among television’s Hollywood shrinks, and has practiced live psychoanalysis (on his program The Therapist) on celebrities like Katy Perry. The singer told him that she’s spent years trying to process her trauma from having grown up amid religious fundamentalists who, among other prejudices, tried to instill in her a profound disgust for the music of Madonna and Marilyn Manson, who they considered agents of the devils.

Singh’s televised sessions seem to stick to the traditional therapist’s manual. He creates a relaxed atmosphere, alternates between circumspect silences and exploratory questions, takes notes and ends sessions with a couple of incisive and insightful observations. His conclusion after a client like Perry? That a celebrity is a human being like any other, and his or her emotional wounds can heal and mend with the right therapy. Even with the cameras trained on them, their sessions broadcasted during prime-time.

Even more questionable are the reality shows featuring Californian addiction specialist Drew Minsky, better known as Dr. Drew. After becoming a minor celebrity on the radio, Minsky took the world by storm with TV series Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew and various related programs. All featured broken toys who needed support in overcoming their harmful habits in order to restart their careers — though critics are right to be suspicious of how helpful televising such support is to the stars in question.

Another therapist who has been accused of less-than-ethical professional practices is the self-proclaimed therapist to the stars Shannon Curry. Curry, a clinical and forensic psychologist, testified in the controversial court case that Johnny Depp brought against Amber Heard three years ago that Heard suffered from severe psychological conditions. Curry, a person described as being “close to Depp,” had examined an unwitting Heard and wound up offering testimony that might leave many potential “star” clients unsettled.

The judge asked Curry if Depp’s lawyers would have called on her to testify if she had detected a mental health condition in Depp rather than in Heard. “I present science regardless of what the science may be,” Curry replied.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.