A pedophile priest recorded his crimes. The Jesuit Order covered up the findings of the investigation

Over decades, a Spanish priest, Lucho Roma, abused hundreds of Indigenous girls in Bolivia. He photographed them, recorded them on video and documented his crimes in writing. This is the second diary of a pedophile priest that EL PAÍS has managed to access. On this occasion, however, the Society of Jesus carried out investigations that confirmed the crimes. But then, after Roma’s death in 2019, they kept them in a drawer, where they remained unpublished. Until today

When the Bolivian ecclesiastical investigators entered the room belonging to the Spanish Jesuit priest Luis María Roma Pedrosa, they found photographs of dozens of half-naked girls in every corner: between the pages of his books, in his personal agenda and on the hard drive of his computer. Many of them were cut out by their silhouettes; others appeared as deformed compositions, like collages, in which the faces, legs and arms of different girls were combined.

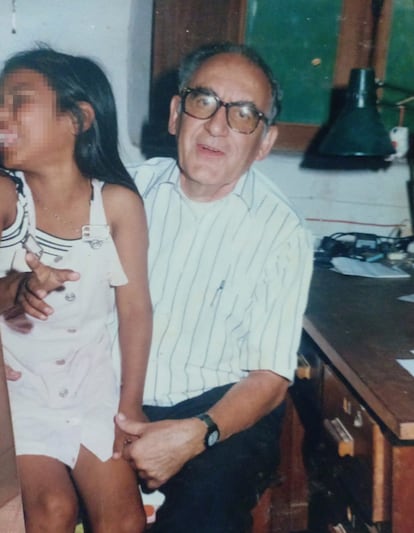

Surrounded by all of this child pornography, the investigators — dispatched by the Church — realized that they were in the lair of a monster. They had arrived at the Jesuit residence in Cochabamba in early-March of 2019, at the request of the leadership of the Society of Jesus in Bolivia. There had been a recent complaint levied against Luis Roma — known as “Lucho” — related to pedophilia and child pornography. The investigators’ mission was to gather evidence, interview witnesses and prepare a report with all their findings.

“It was horrible,” a source from the Society of Jesus — also known as the Jesuit Order — explains to EL PAÍS. “There were dozens of photographs. An attempt was made to identify the girls by copying down the names that were written on the back of the photos… we also checked to see if [names] appeared in the diary.”

“What diary?” asked the reporter.

“Lucho wrote a memoir, in which he described everything: the names of the girls and what he did to them.”

Between 1994 and 2005, during his stay as a missionary in Charagua, a small town in the southeast of Bolivia, Lucho Roma recorded, by hand, how he photographed, filmed and sexually abused more than 100 girls, most of them from the Indigenous Guaraní population. At least 70 of these victims are identified by name in his writings.

Roma detailed the excitement that his perversion gave him and the difficulties that he had while carrying out his crimes. There are about 75 pages in all, in no apparent order, distributed among three different folders. Many of the attacks are undated. This is already the second known diary of a Jesuit pedophile priest in Bolivia. In 2023, EL PAÍS published the memoirs of another criminal Spanish priest named Alfonso Pedrajas.

The discovery of Roma’s memoirs had never been revealed to the public, until today. The disturbing writings were baptized by the ecclesiastical investigators as The Charagua Manuscripts.

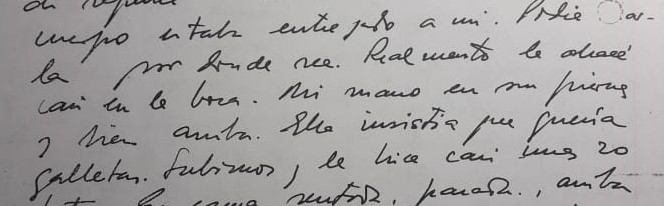

09-27-2000

I could touch her wherever. I almost really devoured her with my mouth. My hand on her legs and higher up. She insisted she wanted cookies. We went upstairs and I took almost 20 pictures of her. On the bed, sitting, standing, up, down, everything.

The inspectors transcribed the diary and commissioned a medical-psychiatric report, so that experts could study the writings and analyze the criminal sexual behaviors of the Jesuit priest. At the time that this process was conducted, Roma was still living in Bolivia: he was in his eighties and confined to a wheelchair. Around 20 clergy members and laypeople were interviewed about this matter. But the victims had no voice in the report. Although the investigators traveled to Charagua, none of the abused individuals wished to speak with them.

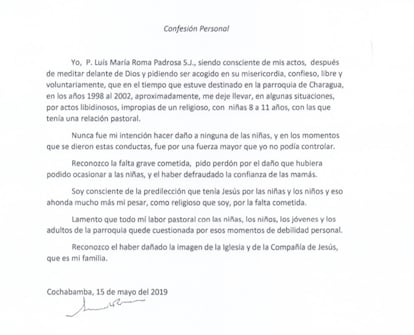

The investigation lasted six months. There was so much evidence against Roma that the accused ultimately signed a confession before a notary: “I let myself be carried away, in some situations, by libidinous acts… with girls between the ages of eight and 11.”

Everything the investigators gathered was included in the devastating report, which confirms the Jesuit Order’s systematic cover-up of this and other cases of pedophilia. But a few weeks before the conclusion was drafted, Roma died in Cochabamba, Bolivia, due to illnesses that he had suffered from for years. He was 84 years old when he passed away on August 6, 2019. Subsequently, the results of the investigation were not made public. The Society of Jesus — the order to which Pope Francis belongs — didn’t inform the Bolivian civil authorities of its findings, nor did it take into account the ecclesiastical inspectors’ recommendation to compensate the victims.

Everything was buried, until just over a year ago. EL PAÍS’s publication of the diary of another Spanish Jesuit priest named Alfonso Pedrajas — in which he admitted that he had sexually assaulted at least 85 children between 1978 and 2000 — caused a media earthquake in the South American country. This caused more cases, like that of Lucho Roma’s, to come to light.

Only after the Pedrajas case caused a scandal did the Jesuit Order inform the Bolivian authorities about the complaint it had received against Lucho Roma, handing over all the documents from the investigation. That is, for a period of four years, the Jesuits hid everything they had: both the pedophilic materials they kept in their archives, as well as Roma’s manuscripts. Only in the face of pressure from the media and the general public did they act. But the justice system closed the case when the victims were not found. All the investigation’s files remained unpublished.

Until now, that is. EL PAÍS has accessed all the expert reports, the interrogations, some of the files that Lucho Roma kept in his room, as well as the internal files kept by the Jesuit Order, which confirm how they hid both this case and others. These include serial abusers that EL PAÍS has exposed, such as Pedrajas and Luis Tó, both from Spain. This newspaper has also interviewed several of Roma’s victims and six of the specialists, witnesses, inspectors and psychologists who participated in the investigation.

These documents reveal more than just the horror of the crimes of a pedophile who abused dozens of girls. They are also proof — never seen before — of how the Church tends to investigate itself, before locking the truth that it has uncovered in a drawer. The Charagua Manuscripts reflect the cover-up that has been taking place for years.

For the first time, an internal Church investigation has been published in detail. And, in this case, it incorporates a first-person account from a serial pedophile.

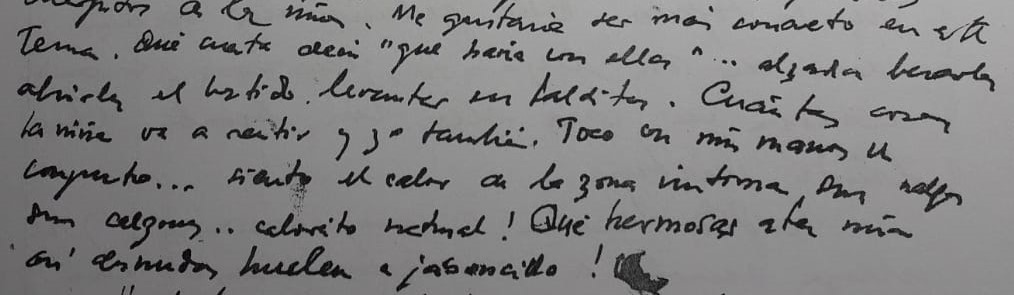

August 1998

A lot of things can be written like this, in longhand. Oh, how badly I write, what bad handwriting, what a lack of ability to express what is inside me: the truth is that I would eat them (...) I touch them all with my hands... I feel the warmth of the intimate zone, with natural warmth! How beautiful these girls are, naked they smell of soap!

THE PROOF

Roma was born in Barcelona on September 12, 1935. He entered the Society of Jesus at the age of 18 and, two years later, he traveled to South America as a missionary, to continue his religious training. Here began a 66-year-long journey as a Jesuit teacher and priest.

The only available biographical data about the first two decades of his life as a clergyman can be found in his CV: he was a teacher at St Callixtus College in La Paz and at the San Clemente School in Potosí, before returning to Barcelona for three years to study Theology (1965-1968). He then returned to Bolivia and became the director of the Tacata Children’s Home, in Cochabamba.

There are also descriptions from some of his colleagues and superiors:

Classified document from the Jesuits, 1987. Provincial Superior Luis Palomera

He is secretive, uncommunicative, unsociable and even very unkind. (...) He seems to show very little interest in what others are going through. He lives in a very personal, segmented, cerebral world… He works in the shadows.”

When Palomera wrote these lines, Roma was working as his right-hand man in La Paz. Both had known each other since their childhood in Barcelona. So, as soon as Palomera was promoted to the position of superior provincial in 1987 — the highest rank among the Jesuits in Bolivia, with a term that lasts between four and 10 years — Palomera went to Roma and asked him to be his vice-provincial at the headquarters of the Society of Jesus in the city of La Paz (Bolivia’s administrative capital). Roma had already been working there since 1983, as national deputy-director of the Order’s educational centers.

It was at this stage that Roman recorded his first sexual assaults. The documents provided by the canonical inspectors indicate that, on weekends, after he left work at the congregation’s offices, he traveled to Yungas — a small region northeast of La Paz — to visit the Indigenous community of Trinidad Pampa. That’s where he sexually assaulted dozens of girls.

His “obsession” — the word that Roma used to describe his penchant for sexual assault — became a constant in 1994. That’s when a new provincial superior, Marcos Recolons, was promoted. He’s now under house arrest in Bolivia, accused of having covered up for several pedophiles during his mandate.

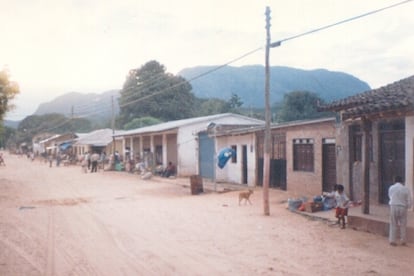

The year of his ascension, Recolons designated Roma to be a missionary in Charagua, a small town of less than 2,500 inhabitants, the majority hailing from the Guaraní Indigenous community. In a letter that he sent to Recolons that same year, it’s clear that this was a highly-desirable destination for the accused.

Then 59 years old, the Spaniard arrived in that impoverished town in 1994. He served as a parish priest and as director of the new school that the Jesuits had opened. Shortly afterwards, he was named a superior of the Jesuit Order in Charagua. He always carried a camera with him — initially a film camera — and got the photos developed in Santa Cruz, the most populous city in the country. Later, Roma bought a digital camera, which allowed him to print the images in his room.

A local resident clearly remembers the day he arrived. “He was the boss. He dressed impeccably; [his clothes] were always freshly ironed,” she tells EL PAÍS. At the time, the Church had great power and influence in the area, thanks to its humanitarian work. This is why it was common for children to always be within the Church. This source says that Roma quickly surrounded himself with minors. “He was the apostle of children: he filled his van with little girls.”

Shortly after arriving, in 1996, Roma began to write The Charagua Manuscripts. The documents only cover up to the year 2001, while the writings found appear incomplete and the entries aren’t always in order. But the stories are terrifying: he details precisely how he gathered the girls into groups, showered with them in his room and took snapshots of them. Days later, he would return to look at these pictures and masturbate.

Charagua, October 31, 1998

Today, 10 girls have passed through my room and I will have taken about 95 pictures of my little darlings.

The conclusions made by the psychologists who analyzed these texts are resounding:

Rome’s calligraphy is also a reflection of his crimes. His handwriting sometimes appears deformed when he describes some attacks. Several words are also circles or underlined with colors. A Chilean specialist analyzed these elements and prepared a forensic-graphological expert opinion. The results were included in the canonical investigation.

The episodes that Roma describes indicate that he followed the same modus operandi to attack dozens of minors: he cajoled the little girls with gifts or sweets and took them on field trips to a stream near the town. On other occasions, he would take groups of girls into his room, where he would lock the door and play children’s movies, or films about the life of Jesus Christ. And, in those moments, he took the opportunity to abuse them and record or photograph them.

Below, you can read the original transcription that the researchers made, using the diary’s fragments that referred to the abuse:

Susana breathes into the phone. She’s 32 years old. Her real name is not being used, so as to protect her identity. She’s mentioned in the manuscript as one of Roma’s 70 victims. She also appears in one of the pixelated photographs that the Bolivian media published a year ago, when the case came to light. “I recognized myself and memories began to come to my mind of the things that happened,” she tells EL PAÍS. Susana was abused between 1996 and 1997.

Her story is a carbon copy of the description in The Charagua Manuscripts, but from the victim’s perspective.

.

Susana narrates that it was common for Roma to have her and other girls sit on his lap, in front of his computer. There, he showed them photographs that he had saved. Each girl had a folder with her name. He printed some of the pictures, so that they could give them to their parents.

.

One day, the Jesuit priest asked her to come to his house alone. After that visit, the abuse ended.

.

The Jesuit authorities still haven’t contacted this victim to offer reparations. They also didn’t wish to respond to EL PAÍS when asked why they’ve refused to do so.

.

Susana contacted EL PAÍS through the Community of Survivors of Bolivia, a non-profit association made up of citizens who suffered abuse within the Church. For the past year, the NGO has been working to locate victims and support them. At the moment, the association is studying the possibility of filing a class action lawsuit against the Society of Jesus for the cover-up of several cases of pedophilia, including the abuses committed by Lucho Roma.

The name of another priest accused of pedophilia also appears in the manuscripts: Francesc — nicknamed “Paco” —, who was Roma’s brother. Also a member of the Jesuit Order, he was living in Barcelona at the time. Several entries detail his visit to Bolivia in the summer of 1998 and how both men enjoyed a school parade together through the streets of Charagua. In December of that year, when Paco was already back in Spain, Lucho wrote about a girl he had sexually abused: “I hope she doesn’t grow up, because she’s at the most beautiful age. Paco would have a lot of fun with this little girl.”

Final report of the canonical investigation

In July 1998, [Lucho] received a visit from his brother, Paco. He suggests to him that he would have fun with some girl… [This] could also merit an investigation.

The case of “Paco” Roma was included in a 2022 investigation by EL PAÍS into abuses in Spain. This newspaper received a complaint from a victim, who, in 1984, suffered abuse at the hands of this Jesuit priest at Casp College, in Barcelona. There’s no formal record of the Jesuit Order in Bolivia having communicated with the Jesuit authorities in Spain about Lucho and Paco, although there are several personal letters which indicate that the superiors in both countries knew about the abuses in the 1980s and 1990s.

The Society of Jesus in Spain refused to respond to EL PAÍS when questioned if the institution was ever notified about the sexual assaults. The Jesuit authorities in Spain simply referred this newspaper to the Society of Jesus in Bolivia. Nor have any details been provided about the numbers of complaints filed against Paco, either in Spain or Bolivia. Paco is still alive today, living in a Jesuit-run residence in the Spanish province of Catalonia.

The report and the manuscripts also reveal Lucho Roma’s schemes to pay for the “gifts” he gave to his victims. He borrowed money, stole alms that were given to the Church, or diverted resources that the Jesuit Order allocated to humanitarian works in Charagua. His deceptiveness caused talk among his colleagues and superiors.

With the embezzled money, he also paid his closest crony: a young orphan he met at the Tacata Children’s Home in the 1970s. Bladi — who is repeatedly mentioned in the manuscripts — was Roma’s driver and companion during some of the excursions he made. His name appears under each of the stones that the researchers lifted. The hypothesis is that his role was vital for Roma to be able to abuse minors.

Final report of the canonical investigation, 2019

Father Roma generated a lot of visual material (videos and photographs), taken by himself in some cases. But in other cases, [the footage] was taken by a third person, whose identity couldn’t be determined. However, it’s presumed that it could be B.V., a protégé of Roma’s. For many years, [the two men] were very close. [B.V.] became a problem for the community, because he constantly demanded money. This link shows that Bladi likely blackmailed Roma.

Neither the investigators nor this newspaper have been able to locate this person to find out his version of events. However, through various sources, EL PAÍS has corroborated his existence and his constant visits to Charagua. “Roma said he was like his son,” a local resident notes.

In November 1998, Roma wrote in his diary that he had some problems. He doesn’t specifically describe what occurred, but his concerns revolve around the photographs and videotapes that he’s been accumulating in recent years, especially in the Yungas region of La Paz: “Will I go back to taking photos and [doing] other things?” Distraught, he mentions in his memoirs that he must ensure that “there are no” recordings of his visits to the village of Trinidad Pampa, “because it’s very dangerous.” Yet, he writes that he’ll keep the negatives of the photos.

In large letters, he baptizes this entry in his diary as “The Great Unknown.” The doubt that gnaws at him: was the door “closed definitively” on his crimes in that particular Indigenous community? The solution he plans is to deliver, through an intermediary, a package of photographs “to interested families.” For the first time, he seems to feel guilty. He speaks of having gone through “a time of trouble” because of his “sin.” However, he justifies himself by saying that God has made him as he is. He alludes to the fact that his actions don’t depend on him, but rather, on divine providence.

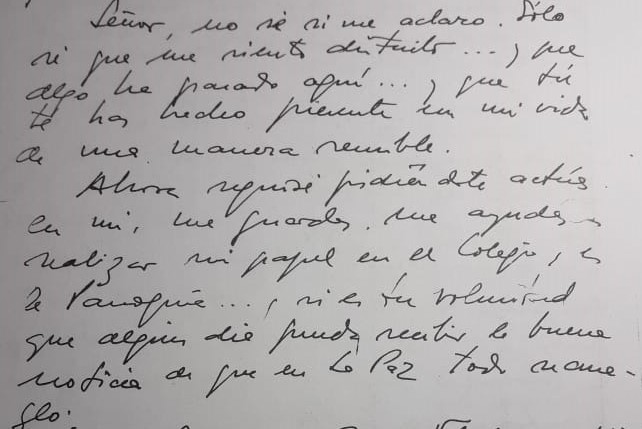

November 1998

Lord, I don't know if I'm making myself clear. I only know that I feel destroyed (...). Now I will continue to ask you to act through me, to keep me safe, to help me to carry out my role in the school, in the parish... and, if it is your will, that one day I may receive the good news that in La Paz everything has been resolved.

But Roma managed to return to Trinidad Pampa. In the manuscripts, he details the preparations for a trip there, in Christmas of 1998. He writes that he’s excited about the idea of “spending 10 days in the Yungas with the local girls, with the weather, the video recorder, the camera, the photos, my singing, the movies that they like.” He mentions several people — including Bladi — who are helping him organize everything: car trips, a camera, accommodations, money...

After the visits, he returns to his diary to describe how the photo sessions went: “The experience has been impactful, shocking, captivating.”

Weeks after those “vacations,” he writes again with some regret, aware of the damage he may have caused: “I must have made some of the families bitter because of my lack of maturity and because of what it meant for me to be locked up with the little girls.” After this apparent repentance, Roma decides to change and stop committing sexual abuses.

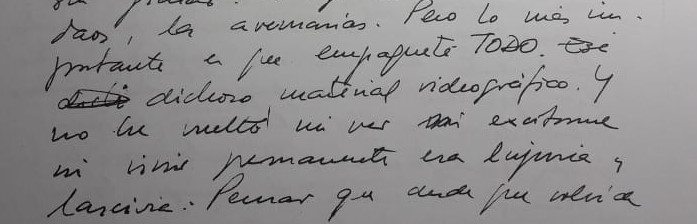

March 24, 2000

I packed up all that damned video material and I have resolved not to watch or get excited or live permanently that lust and lasciviousness. To think that since I came back from Trinidad Pampa in January it has almost been a daily thing to watch and watch the same thing again. What an obsession and what a sick emotionality. (...) I really felt "sick." (...) I start to think... but what a piece of crap that stuff is. I even seem to feel disgusted...

But he only stops for 76 days. After that period, he returns to abusing, photographing and filming girls in Charagua, according to what appears in his manuscripts. His diary ends in September of 2000 with him acknowledging his pedophilic nature: “What can I say about the obsession? For God’s sake, I get scared at times... I see myself as ‘abnormal,’ as a harasser of girls, as a potential rapist, as a danger to those little ones!”

THE INTERROGATORIES

Roma continued in Charagua until 2005. That year, suddenly, he was transferred to Sucre, the de jure capital of Bolivia.

.

Roma took all the pedophilic materials to Sucre in his luggage, thinking that nobody would discover his secrets. But that’s not what happened. Roberto — the fictitious name of one of the Jesuits who lived with Lucho in Sucre for some years — discovered the archive of horrors.

It took Roberto more than 10 years to report those photos. He did so after leaving the Jesuit Order, giving them to a journalist from the EFE — the Spanish international news agency — named Gabriel Romano. A former Jesuit himself, Romano went to the headquarters of the Society of Jesus before publishing his report.

The provincial superior at the time, Osvaldo Chirveches, assured Romano that he knew nothing about these incidents and promised that he would open an investigation. Romano published that the Jesuits were conducting an internal investigation into a new case of abuse, but in the report that he filed, he didn’t identify the aggressor, nor the locations and dates of the attacks.

As promised, the Society of Jesus posted a statement on its website with Roma’s initials and assembled a group of investigators. Among them were Jesuits who held high positions in the Order — such as the aforementioned former provincial superior — and a former high official of the Order in the Vatican, Marcos Recolons.

Recolons — who now stands accused of protecting pedophiles — was one of those who entered Roma’s room to conduct a search. He was also present during the questioning of high-ranking Jesuit officials in Bolivia. The questions were brief and didn’t delve into how much they knew about cases of abuse within the Order.

Other team members had a more proactive attitude than Recolons. Daniel Mercado, a Bolivian Jesuit who specialized in bioethical medicine, was one of those who moved heaven and earth to ensure that justice was done. Mercado died in 2021. Today, one of his colleagues describes his role in the investigation: “He went around Charagua in search of victims, located the Jesuits for interrogations, managed to have the issue addressed internally, and tried to ensure that individual responsibility was taken, in the face of the cover-up that we discovered.”

This source reveals that, during the interrogations, at least two people declared that they saw Roma’s child pornography and reported it to their superiors. One of them was Óscar Gutiérrez, another Jesuit who worked with Roma in Sucre.

.

I deleted what I had seen and then spoke with Father Menacho. I told him: 'Antonio, I found this on the computer. I listen to music [often] and I’ve never had this happen, not until Lucho’s computer broke down.' I told him that I deleted the files out of fear. He was also scared. I left, but he came looking for me after 10 minutes. He asked me if I was sure about what I saw. That is what I saw.”

Father Menacho denies that this conversation ever took place.

This wasn’t the first time someone claimed to have seen Roma’s material: a few years earlier, a worker found his secret stash.

.

I know it was in Charagua. [In the photos where Roma appears abusing girls], there was a striped blanket. Lying on the bed, it looked like he was having sexual relations with the little girls. It was clear that he was penetrating them. I saw that there was a sexual relationship, not only in one photo, but in several. I didn't want to talk [about this] to anyone: they could say it was slander, they could do something to me alleging false testimony…”

Despite her fear of repercussions, this woman recounted everything she saw in 2016 to another Jesuit, César Maldonado. And this is what Maldonado himself said during his interrogation: “As soon as I found out, I notified the [provincial superior]. This was a little more than two years ago, [in 2016]. I would have responded more forcefully if I had known that they wouldn’t do anything. I cannot prove it, but I’m sure that his superiors knew and did nothing.”

THE RESULTS

With the initial investigations complete, Daniel Mercado didn’t waste any time: he wrote up the conclusions of the report. In April of 2019, according to internal documents of the Order, he contacted the man who was the provincial superior at the time, Osvaldo Chirveches, to tell him about “pending issues” that the Jesuits should address.

The most urgent course of action he recommended was to offer reparations to victims — although he didn’t specify what this should consist of, whether it be psychological assistance, asking for forgiveness, or giving monetary compensation — “out of human and Christian responsibility.” Other recommendations included searching for the girls who suffered from the attacks and reporting internally on “the magnitude of the abuses committed.” Mercado wrote that other cases of sexual abuse should be investigated, while urging that the action protocols be updated. He advocated for the replacement of delegates sent by the Order with anti-abuse specialists, who were “independent and morally sound.”

Chirveches didn’t fulfill any of these recommendations. The Society of Jesus in Bolivia has refused to respond to EL PAÍS regarding why it didn’t report this case to the police in 2019. The Jesuits have only limited themselves to saying that the current provincial superior, Bernardo Mercado, was appointed to his position in June of 2022 and “has barely managed to review the files” of the efforts of his predecessors. All that he knows is what has been published by EL PAÍS.

Final report of the canonical investigation

It has been established with a high degree of probability that these events were known to the provincial superiors of the communities in which Father Roma lived. These officials never acted with due and timely diligence to investigate the events or punish the perpetrator, nor did they reach out to victims in an effective manner.

There’s no evidence that the Jesuit authorities delivered the complete summary to the Vatican, as the inspectors also requested in their report (several of them have confirmed this to EL PAÍS). The Jesuits also didn’t implement what all the experts — psychologists, psychiatrists, investigators and specialists — strongly advised: to find the victims, care for them and seek formulas to repair the damage caused. It took three years after receiving the report for the Society of Jesus to publish a statement, in which they reported that the investigation into complaints against LMRP (utilizing an acronym, without giving Roma’s identity) revealed “plausibility about what was reported.” The Order merely asked for forgiveness.

The files from the Roma case are an indication that horrifying documents — which describe how clerics have attacked children with total impunity — are still hidden in the secret archives of the Vatican. These are portraits of monsters, who had the protection of their superiors.

EL PAÍS launched an investigation into pedophilia within the Catholic Church in 2018 and maintains an updated database with all known cases. If you know of any case that hasn’t received attention, you can write to us at: abusos@elpais.es. If it’s a case in Latin America, the address is: abusamerica@elpais.es.

Credits

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition