‘The Church’s silence is shameful. They knew about the abuse for decades’

In an interview with EL PAÍS, the nephew who found his uncle’s secret diary, in which the Jesuit priest revealed that he sexually abused dozens of minors during decades, says: ‘You’re with the victims or with the pederast’

In 2018, EL PAÍS launched an investigation of pedophilia in Spain’s Roman Catholic Church and developed a database with all the known cases. If you know of any unreported cases, write to us at abusos@elpais.es or abusosamerica@elpais.es if the case is in Latin America.

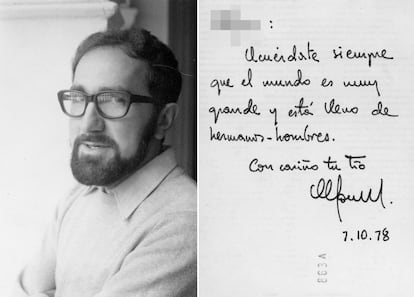

What seemed like an ordinary cardboard box changed Fernando Pedrajas’ life. It happened in early 2021 amid the pandemic, just before an unprecedented snowstorm blanketed Madrid in white. Fernando’s mother had died a few months earlier, so he had gone to the family home to sort everything out and put it up for rent. He went down to the storage room and found a dusty box with “PICA” written on it. It belonged to his uncle, Alfonso Pedrajas, a Jesuit priest known as Padre Pica who died of cancer in 2009. Inside the box were a few things that had been sent to Fernando’s mother from Bolivia, where Pica served as a missionary: his passport, some books, a handful of photographs and a green file folder with what appeared to be his uncle’s journal. Typed on the first page was one word: Historia.

This is the inside story of a sexual abuse case that has shaken Bolivia. As Fernando Pedrajas read the document in the dusty cardboard box, he learned that his uncle — Father Pica — had abused dozens of minors while he was a teacher in various Jesuit schools in Bolivia, where he lived from 1960 to 2009. Pica wrote that he confessed this terrible sin to his Jesuit superiors, who covered it up. Fernando turned the journal over to EL PAÍS, who published the story in Spanish on April 30 and in English on May 5 with interviews of the victims and their relatives. Within 48 hours of the publication in Spanish, Bolivia’s attorney general launched an investigation, and the Jesuits dismissed eight former high-ranking members of the order. The Bolivian Roman Catholic Church issued a formal apology and asked for forgiveness. In Pica’s native country, the Spanish Episcopal Conference replied to our questions with one sentence: “We share the feelings expressed by the Society of Jesus in their statement and support their initiatives regarding this painful case.”

Fernando Pedrajas, the pederast priest’s nephew, agreed to tell us how it all happened.

Question. How did you feel when you read the journal?

Answer. It was a while before I read it. I saw it was worth looking at, but left it in the box. I began reading it months later when I emptied the house to rent it. It was enjoyable at first as he tells how he traveled hundreds of kilometers throughout Bolivia to celebrate mass and help the poor. I thought it was beautiful. But as I read on, I discovered Pica was a pederast and that the order protected him. I felt fear and disgust. I was shocked and felt completely let down.

Q. What was your relationship with him?

A. I always felt we had a certain connection. He had some artistic gifts that I identified with. I think he felt the same way. I started playing the guitar when I was 10 years old, and Pica was one of my first teachers.

Q. What happened when you told the rest of the family?

A. That also took me a while. I first had to digest and assimilate it all. In February 2022, I emailed my whole family and sent them the journal. I can count the responses on one hand. I think they prefer to look the other way.

Q. What did you do next?

A. I knew I had to do two things: turn everything over to the authorities and go to the press. I wrote another email outlining the story and sent it to Luis Carrasco, the current director of the Juan XXIII School [that most of Pica’s victims attended]; the board of directors of the school’s J23 alumni association; all the organizations dedicated to protecting child abuse victims I could find on Google; and to the main news media outlets.

Q. What were the responses?

A. I received many replies from the news media, but I wanted EL PAÍS to have the story because it was already investigating the issue and had a presence in Latin America. The first person who contacted me from Bolivia was Luis Carrasco, the current director of the school. He told me he knew nothing about this and therefore he couldn’t help. He alerted the Jesuits, and a priest named Osvaldo Chirveches contacted me. Chirveches is a former provincial director and the current director for safe environments in the Jesuit order.

Q. What did he say?

A. He asked to meet with me. I agreed, but said I would also like Carrasco to attend, and copied him on my email. He [Carrasco] emailed saying he couldn’t take part in that meeting since he didn’t have an [adequate] internet connection. That was the last communication from the director of the school where my uncle abused countless children. That’s when I decided to go public with all of this.

Q. Did you continue to communicate with the Jesuits?

A. Yes, Chirveches was very insistent that I send him the journal. But I didn’t trust him.

Q. What about the Spanish ecclesiastical authorities?

A. I took the complaint to the archdiocese of Madrid, where I live. But I couldn’t get anyone’s attention. I went five times and never could identify someone who would receive the complaint and document. I left my name and contact information, but no one ever called. Unbelievable... I gave up.

Q. What happened with the alumni?

A. I offered the journal to the alumni association in case they wanted to use it to file a complaint in Bolivia. But I said if they wanted to publish it, I preferred for the press to do it first. I felt it essential that everything be verified before publishing. They decided not to accept the journal or file a complaint. I continued communicating with them cordially and they were always very cooperative. They should have the journal right away. It belongs to them and they should read it.

Q. Did they help you locate the victims?

A. Yes. The victims are the key to everything from now on. I would like to say to them and others I haven’t met that I’m very sorry they had this terrible experience — I can’t even imagine. But also that they’re not alone.

Q. You took the case to the public prosecutor [in Spain].

A. Yes, but it was filed away. My uncle is dead, and the statute of limitations has expired. A victim testified from Bolivia, although the alumni association decided not to support her. But I intend to reopen the complaint so that the people who knew about Pica’s abuse and covered it up are held accountable. I also want to form a victims’ group who will support a general complaint filed here in Spain. They can remain anonymous. I know many victims who haven’t spoken out yet, and I’d like to tell them this: many of you occupy important positions in the Bolivian government. Your collaboration is important. I encourage you to email me at asociacionvictimasj23@gmail.com. It’s time to act.

Q. The journal is also a story about a cover-up.

A. That’s the most alarming part of this. It’s so disgusting… I don’t even know what to say. They can’t hide behind the seal of confession. Marco Recolons [the only person involved who spoke to EL PAÍS] should be put on trial. If it’s proven that he knew [about the abuse], he should suffer the consequences. The Church’s silence is shameful — they knew about the abuse committed by Pica and other Jesuits for decades. They covered it up with lies and are still lying.

Q. They are still lying?

A. Yes, they have received more reports of abuse by Pica and other priests.

Q. What do you think about the reaction to the report published by EL PAÍS?

A. There is one very positive outcome. The Jesuits dismissed eight people within 48 hours, something that has never happened so quickly and thoroughly. It’s more evidence that they were aware of the situation. This happened because of the report, which fortunately also had a surprising impact on the Bolivian media and institutions.

Q. What do you want to happen now?

A. We are looking at the tip of the iceberg. Let’s hope that, at the very least, those who covered up all of this and are still alive will be tried and convicted. And the Catholic Church should pay reparations to the victims.

Q. Many people think you have been unusually courageous by deliberately tarnishing the name of a relative.

A. I don’t think so. I think families of abusers should step up and firmly denounce what their relatives have done. There’s no middle ground here — you’re with the victims or with the pedophile. You denounce their behavior or cover it up. There are no nuances to it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.