‘The greatest privilege is stopping’: Why time devours us, and how social media could help

Philosophers, scientists and writers debate how time is a construct that we created in order to self-destruct, and how we could try to overcome it

Last Christmas, we were filled with distress by a column by writer Manuel Vicent. The text, titled El tiempo (Time) and originally published in EL PAÍS in 2009, went viral during the holidays, perhaps because only when the routine is interrupted do we find a few seconds to attend to issues like those raised by the writer. “Time does not exist,” Vicent begins. “Time is only the things that happen to you. That’s why it passes so quickly when nothing happens to you anymore.”

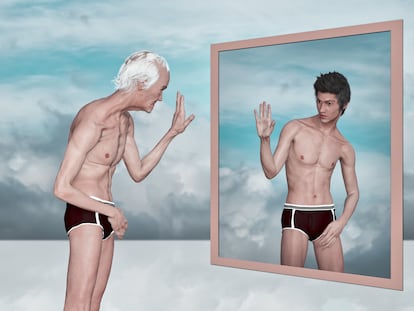

Time is a problem that has always occupied philosophers, physicists, mathematicians, theologians, filmmakers, farmers, basketball players, musicians and writers — in other words, everyone — and its nature has been the topic of thousands of discussions. One of the most famous was the one between physicist Albert Einstein and the philosopher Henri Bergson in 1922, a debate that kept the entire press of the time in suspense. In the end, the scientific view of the former prevailed, but the feeling of overwhelm, as well as the distress caused by time never being enough, continued to grow throughout the 20th century.

The truth of the matter is that our experience of time has less to do with physics or metaphysics than with the way our societies are organized. Ever since Shakespeare put the phrase “The time is out of joint” in Hamlet’s lips, as we have accumulated technologies and contracts, things have only gotten worse.

Social acceleration: Two sides to a phenomenon

Hartmut Rosa is one of the authors who have best described the relationship of contemporary societies with time. In essays such as Alienation and Acceleration, he argues that social acceleration is an obstacle to the fulfillment of a good life and that we are dominated and repressed by a temporary regime that could be disputed and transgressed, because, although it may seem that way, it is not a natural force beyond the reach of politics. In short: we feel that the hours are losing substance because they contain more and more activities, and our pace is so frenzied that it even overwhelms our ability to perceive everything that happens to us in an orderly manner.

On the other hand, if culture seems stuck in nostalgia (the so-called retromania) it is because the endless demand for novelty — from digital platforms, for instance — has surpassed the imaginative capacities of the creators, who, paradoxically, have had to look back in order to keep the number of yearly productions growing: in film, new installments of movies that already existed; in music, covers of the biggest hits of the past.

Rosa uses the timely example of a debilitating cold to illustrate how there are phenomena that, despite the widespread acceleration, cannot be compressed in time, and insists that the causes of this acceleration are always social: technology facilitates it, but most of all it would be caused by the competition between contemporary professionals (in modern societies the status of an individual depends on their performance) and by the desire to accumulate varied experiences within a finite life (now that a religious belief in another life after death is no longer the norm).

Andrea Genovart is the author of Consumir preferentemente (Best before), a novel whose protagonist shares a trait with all the young people of her generation: the feeling that, both literally and metaphorically, she is always late. The writer confirms that, today more than ever, “we experience time in a problematic way and with many contradictions.” “We complain that we don’t have time,” explains Genovart, “that everything is fleeting and passes us by. But at the same time, we ourselves operate by a logic of productivity and don’t feel comfortable with ambiguity, suspension, patience or waiting, which are things that resist accelerated temporality. In the end we are not at ease with any of the forms of time.”

For his part, Miguel Ángel Hernández, teacher of art history and author of El don de la siesta (The art of the siesta), practically a pamphlet against haste and in favor of snoozing, points out that “the reflection on the transience of time and evanescent time is purely baroque,” and explains that “what would be typical of modernity is not the awareness of the end, but an elimination of the time necessary to think about the end. The assembly line time does not allow pausing and thinking, it does not allow metaphysical time, and the pause is essential to break free from of that repetitive, almost cinematic time, and to be able to experience what Byung Chul Han calls the aroma of time.”

The fear of being left behind

Hartmut Rosa is categorical: social acceleration is a totalitarian, omnipresent regime that terrifies those who are subject to it (that is, all of us). Our lives are subject to countless deadlines, calendars, schedules and other temporal limits that serve as a silent set of rules whose unfulfillment could leave us behind. And the fear of being left behind (unemployed, sick or unable to keep up) is what pushes us to accelerate and to use for productivity every moment of what could have been free time.

In this context, making a pause or giving yourself a break (just a vacation, for example, in the case of a self-employed person) is a class privilege. Genovart explains it like this: “The greatest privilege is to stop pleasurably. You may have done it because you are unemployed or because of a health problem, but you will experience that with guilt or distrust. When you stop and live it pleasurably, it is because you project security, because there is no possibility of loss thanks to a cushion or to relationships that can always come to the rescue. There are times when life forces us to change course and slow down, and if we do not enjoy that privilege, we experience the lack of guarantees in a very distressing way.”

Hernández goes further and states that boredom is, too, a privilege, “because it means having free time,” and an achievement “because it means not using those times that in the end we all have.” “Boredom is one of the necessary conditions for thinking. We need it to find things without looking for them. But today no one gets bored anymore. We use up all of our time, making it productive for ourselves (because we get work done) or for the system (because we consume entertainment or any other merchandise). There are no downtimes because we always have something on hand to take advantage of the ellipses.”

It is a structural problem, and many experts warn that some individual deceleration strategies (which usually consist of “retreats” or a “disconnection” with a deadline), which they refer to as “functional deceleration,” covertly perpetuate the logic of acceleration: in reality, these quick fixes actually serve to regain strength in order to perform better as soon as possible.

Internet time, entertainment time

E.P. Thompson was one of the first authors to become concerned with temporal discipline in industrial societies. He studied everything that “the clock demands of workers.” Today, we add to these demands those imposed by entertainment culture: we, viewers, must be always up to date.

Genovart believes that we do not have time to enjoy (or even to fully understand) the films we watch or the news we read: “There is an assimilation between what is seen and what is perceived that does not take into account the fact that rescuing knowledge from entertainment takes prolonged time. Entertainment culture does not contemplate a dialogue with what it proposes; it is designed so that you do not return to it. And it is precisely revisiting a proposal what allows you to think about it as you process everything that you were not able to discover in a first encounter.”

Although the internet, with its infinite scroll, seems to reinforce this dynamic of disposable content, it could also (with its apparent suspension, and the loss of references that moving from link to link or thread to thread entails) be proposing new forms of temporality. “The scroll is a vertical line along which you descend without being able to go back,” explains the writer. “What the internet provides is a community feeling within the temporal experience. To belong to a community, you must assimilate the contents at the speed they are offered, and there is an obligation: just as you check if your cat has food, you must check that you haven’t missed anything new. That potential loss is that of belonging to a community that shares, laughs, comments... You have to operate at certain speeds if you do not want to end up alone, facing a crowd. The temporary and community experience combine, something that differs from the idea that one chooses alone, in isolation, what one will see on a digital platform.”

“On social media,” Hernández continues, “there is a pure present that continually falls behind. It is the timeline of X (formerly Twitter) that discards what happened yesterday — or three hours ago. Stories, statuses and photos have no sense of permanence or memory (I write or photograph something in order to leave a record); they have a here and now. We’re sharing a ‘now’ that will have no meaning later.” However, although social networks, as a link between what happens outside and what happens inside the internet, remain in a perpetual, pressing present, the online world as a whole would be, “the world without time and without space that Saint Augustine imagined in The City of God. Everything at once everywhere, even if your body is not the Augustinian one, but one sitting in a specific context that we don’t see. But on the internet there are no schedules and no dates: past and present intertwine, as in an archive and repository of everything.”

Writer Mieke Bal studies the work of artists like Stan Douglas and Jussi Niva, who questioned the contemporary uses of time by involving, almost kidnapping, the viewer. But beyond contemporary art, where examples abound, or some fictions (from Alice in Wonderland to Tenet), our time management is barely discussed, even though, again according to Rosa, “it causes real suffering in millions of people.” Miguel Ángel Hernández suggests looking back and taking advantage of close examples: “I remember my father sitting under the fig tree, looking at the horizon, every afternoon, after coming home from work. Was he bored? I don’t know. He inhabited time. He was with himself.” And, even though time makes us suffer, we must not forget that, beyond the atoms, it is a social construct.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.