Big butt fever: behind the dangerous reputation of a surgical procedure

One of the techniques used for the cosmetic intervention, the so-called “Brazilian butt lift,” has a complication that can cause death

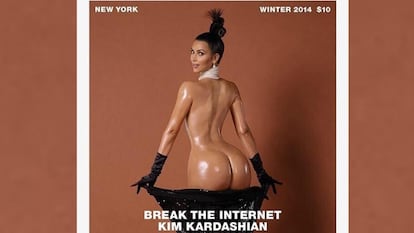

In 1992, the rapper Anthony L. Ray, known in the then-niche hip-hop community as Sir Mix-a-Lot, achieved fame because of a song titled “Baby Got Back,” which for the first time in music history spoke of having large buttocks in a positive, and flattering, light. Though the song was initially controversial because of its explicit sexual allusions, that physical characteristic, in the context of a specific racial group and gender, was now suddenly publicly legitimated. The song was on the Billboard Top 100 for almost five weeks, and it won a Grammy in 1993 for Best Rap Solo Performance. VH1 later included it in its list of best songs of the 1990s. Thirty years later, big butts remain an aesthetic trend. In pop culture, they have become an aspirational feature, reclaimed by a series of divas, from Jennifer Lopez, Janet Jackson and Nicki Minaj to Kim Kardashian, whose behind is so celebrated that, when she decided to fully uncover it in Paper Magazine, it almost exploded the internet. Kardashian has repeatedly refuted allegations that she increased the volume of her buttocks in the operating room, in an operation that physiques like her own have brought into the canon of cosmetic procedures. Gluteoplasties are growing more and more common. Isabel Moreno, president of the Spanish Association for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (AECEP), calculates that “we are likely reaching an increase in demand around 50% in Spain.”

In an episode of the last season of the 2021 series The Resident, an girl arrives at the emergency room, almost unconscious. After a series of tests and checking her social media, it is discovered that, that very morning, she had undergone a Brazilian butt lift, or BBL, as the intervention is commonly called. The woman, presented with all of the stereotypes of an influencer, had suffered a fat embolism, one of the surgery’s most well-known complications, which can lead to death.

Medical television shows, like 90s music videos, do not tend to be a reliable source from which to draw serious conclusions, but it’s not unusual for their subplots to have a basis in reality. In this case, a quick Google search returns headlines about the risks of the operation that has become a global phenomenon, which many now see as the most dangerous cosmetic surgery procedure. But how true is that label?

Most news stories that alert about the dangers of the operation, which consists of obtaining fat from another part of the patient’s body and use it to remodel or increase the glutes, refer to a 2017 report in the Aesthetic Surgery Journal. As the intervention was growing in popularity, and news of associated deaths occasionally appeared, an exhaustive study was carried out to gather data ad offer recommendations about its true risks.

“The risk published in that study was that out of almost 199,000 gluteus injection procedures, 32 patients died from a fat embolism,” explains plastic surgery specialist Dr Eloísa Villaverde. It is a “relatively small” risk, but it still outweighs that of other cosmetic procedures, in which “the risk of death is much lower, practically non-existent in many.”

The potentially fatal complication, the fat embolism, occurs because “traditionally, the gluteus fat injection technique infiltrated the fat into the muscle and subcutaneously,” the plastic surgeon explains. “The risk occurs if the fat infiltrates into the gluteus maximus muscle and embolisms arteries or veins located inside of it, above all in the deepest part. In that area, the vessels have a considerable width, two to three millimeters, and if an embolization occurs, fat can move through the blood to the lungs and have fatal consequences. In other areas where fat injections are done, like the breasts, the risk is practically non-existent,” she explains. Because of that and other studies with recommendations for surgeons, “the fat injection technique in the gluteus is safer,” Isabel Moreno affirms. “It is no longer injected into such deep areas where there is less risk of a fat embolism are, and the cannulas are a higher caliber,” she explains.

In fact, the president of the AECEP points out that, among the three most common butt augmentation surgeries—implant, flap and fat injection—the last is “the one with the lowest rate of complications [at 6.8%], with a big difference with the prosthetic [31.4%] and the flap [23.1%].” The numbers come from an analysis published in 2019, though fat injection surgery is the only one with risk of an embolism.

Why do they turn out so badly?

Butt augmentations were just “anecdotal” some years ago, explains Dr Villaverde, but now they are increasingly frequent, and demand has increased. Carmen Flores, president and spokesperson for the Spanish organization Patient Defense. As the organization only receives failed cases (“no one comes saying ‘they did an amazing job’”), she has a very clear idea of where the problem almost always lies, as much for the buttocks as for any other aesthetic surgery. “There is a legal void that needs to be filled. It should not be allowed for a doctor to take a short course and then begin operating, but that loophole allows it: they aren’t doing anything illegal,” she says.

In January, Sara Gómez Sánchez died after an cosmetic surgery operation in a Cartagena private clinic. Cases like hers, or like fat embolisms in gluteoplasties, demonstrate the importance of patients putting themselves only in the hands of doctors who specialize in plastic, cosmetic and reconstructive surgery, for which, as in other medical specialties, five years of experience are required. It is not enough to seek out surgeons with other specializations. “It’s as if I started doing heart surgery,” says Dr Isabel Moreno, president of the AECEP. Legally, she could do it. This week, the Spanish Society for Plastic, Reconstructive and Cosmetic Surgery (SECPRE) denounced in a Santiago de Compostela conference that 80% of cosmetic operations in Spain are not conducted by specialists.

Moreno believes that cosmetic surgery has so many infiltrators because of “greed and demand.” The people most affected tend to be patients with few resources, as Carmen Flores sees in the cases handled by the Patient’s Ombudsman. “When they try to report it, they also encounter a lot of obstacles: they have spent money on the operation, or they have applied for a loan, and they don’t have enough to pay for an expert examination, which is essential in these cases. Or sometimes they need another operation and the clinic wants to charge them for any change. I think the people who want to have plastic surgery, for any reason, need to be a little more protected by the law. Because it’s the same as ever: nothing happens to those who have money. Those who don’t end up with problems,” she says.

“I don’t operate on everyone and I think most cosmetic surgeons are like that. I operate on those who asks me for something logical and that I think will improve them,” explains Isabel Moreno. Additionally, it is not always possible or recommended to do certain interventions, as Dr Villaverde notes. “At times, some surgeries are unsuitable for patients who demand them, and we have to communicate that to the patient so they understand,” she says.

In a scene of that same episode of The Resident, one of the doctors remarks to another that the patient, now fighting for her life, did her Brazilian butt lift in a dermatology clinic. The other doctor is surprised and indignant. “Unfortunately, in this state, anyone with a medical license can do cosmetic surgery,” the first doctor replies.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.