In Spain’s Canary Islands, citizens document the rebirth of a burnt forest

A project called Fénix Gran Canaria has collected 3,000 images shared by residents following a devastating wildfire that consumed 9,800 hectares of land in August 2019

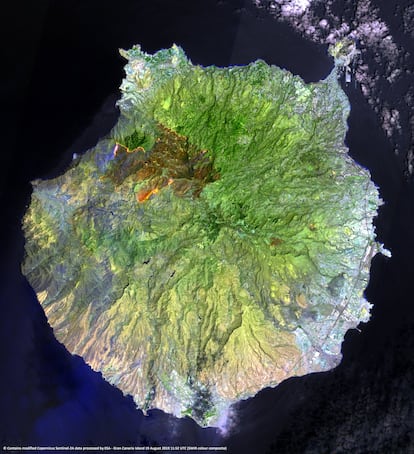

In August 2019, a wildfire allegedly caused by power lines on the Spanish island of Gran Canaria raged for 20 days, burning through 9,800 hectares of land. A lot of of this territory was located inside protected areas such as the natural park of Tamadaba, an environmentally important space containing 7,500 hectares of Pinus canariensis, or Canary Island pine, which is endemic to the archipelago. Tamadaba is considered the green lung of the island, and residents watched in horror as 32% of it was devoured by the flames.

The images of charred trees and blackened earth are still fresh in the memories of the locals. The fire consumed 8% of the island’s forests and also left a trail of emotional trauma behind. “The people of Gran Canaria were watching the island burn and wondering how they might help,” recalls Roberto Castro, a forest engineer who was the first to identify the burnt areas along with his colleagues Diego Cabrera and Víctor de León. It later occurred to them to get neighbors involved in a project to document the damages as well as the gradual recovery.

Their starting point was heartbreaking: the landscape offered nothing more than pine skeletons and lifeless earth – no plants, no animals. Of particular concern was the absolute absence of undergrowth that is typically found under the pines. As for the trees themselves, they are a hardy species that tends to grow again on its own.

This was the backdrop for Proyecto Fénix Gran Canaria, an education initiative seeking to get citizens actively involved in the recovery of this natural space, as a complement to official reforestation measures. The main idea revolves around 16 wooden posts or “totems” placed along trails and viewpoints that cross burnt territory. Participants are asked to place their cellphones on a precise spot on the post and take a picture to later share on social media. Because the shots are all taken from the exact same spots, they provide an ongoing view of the area’s evolution.

Residents responded well to the idea and the Fénix project has now collected 3,000 photographs taken at various points in time, and which have also been available on social media. The story they tell is one of amazing recovery: where there was nothing more than charred tree trunks there are now green pines, and some low brush has already grown underneath. As a matter of fact, 80% of the burnt area has already made a recovery in terms of the landscape.

But rebuilding the entire ecosystem will be more complicated, because a pine forest is much more than a series of trees, notes Juli Caujapé, director and researcher at the Viera y Clavijo Botanical Garden in Gran Canaria. These forests are normally home to other endemic plant species, not to mention animals and underground organisms that help plants absorb nutrients. “That is what’s still missing, and it takes many years to re-establish the relationships between insects, animals and plants that bring sustainability to ecosystems,” notes Caujapé.

This is why it is essential to use scientific criteria to restore burnt spaces. The botanical garden keeps seeds of endemic plant species, to be used only “if strictly necessary to help nature along, as its times are not human times, they are much longer.”

Forest management

The creators of the Fénix initiative are now working on part two of the project, which involves sharing information about daily forest management. “The people who follow us want to know more about nature, about the island,” says Castro. “We are telling them how the forest is turning green again 24 months after the wildfire, we are telling them about the process.”

The project website also provides information about weather events that are typical to the Canary Islands, such as the so-called “horizontal rain” caused by the trade winds. There is also information about singular trees in the area, about the problems caused by climate change and bad land management, and about environmental characteristics that are specific to the Canary Islands, which are located off the western coast of Africa, around 100 kilometers from Morocco at their closest point.

The success of the project on social media has been such that the regional government’s environmental department has reached out for a collaboration. Castro feels that the coronavirus confinement helped get people interested in the Fénix initiative.

“Earlier, the summit of Gran Canaria was largely viewed as just a place to have a picnic or spend the day, but after the confinement you could tell that something was changing, that people wanted to know why that pine tree was perched on that rock, or the name of the rocks that they were looking at. And we try to explain. Without losing track of technical criteria, we try to focus on issues that will make you think, ask questions and reconsider things.”

“Fire prevention involves educating the public,” agrees the director of the botanical garden. “Because 100% of the causes of fire in the Canaries have to do with humans, either out of carelessness or intentionally.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.