Targeted amid coronavirus fears: ‘While this lasts, I ask you to consider moving’

Health workers, supermarket cashiers and coronavirus patients in Spain say that they have received abusive messages from neighbors who are afraid of contracting Covid-19

Silvana Bonino, a gynecologist at a private clinic in Barcelona, was heading to work on Tuesday when she discovered that her car had been spray-painted with the message “infectious rat.”

“At first I couldn’t believe it, I didn’t understand. I was surprised and sad to be the target of this attack,” she told the Spanish news agency EFE, which published a photo of the damaged vehicle. The car, which was parked in the communal parking lot of Bonino’s building, also had two punctured tires. The doctor returned home “very upset” and had to borrow her parents’ car to go to work. It was her husband who convinced her to report the incident to the Catalan regional police, the Mossos d’Esquadra.

The head of the Barcelona College of Physicians (COMB), Jaume Padrós, contacted Bonino on Wednesday to express his support, as did the lawyer for COMB, who indicated that the case could be considered violence against health workers.

“I think it is despicable and I feel sorry for people like that,” said Bonino. “I have never had a problem with anyone.” The doctor has said she did not know who was responsible “but the saddest part is that it could have been a neighbor.”

We want to ask you, for everyone’s sake, to look for another homeAnonymous message left addressed to a supermarket worker

Bonino is not the only person to be targeted amid coronavirus fears. The day that Clara Serrano told her roommates she had the virus, her landlord told her she had to leave. “He told me I was selfish because, working where I do, I knew I was going to get infected,” says Serrano, who is a 31-year-old nurse from Spain’s east-central province of Cuenca. For more than a month, Serrano has been working in a Madrid ward for coronavirus patients. According to her, she “always maintained a safe distance” from her roommates. “I decided to go to the kitchen only to cook and wash my clothes, and I was eating in my room,” she explains.

On March 19, she began to experience symptoms and became stricter with her isolation measures. “I began to use a separate bathroom, and we took turns using the kitchen, disinfecting it before and after,” she says. However, four days later when she tested positive for Covid-19, the response was clear: “You are going to have to go.”

Hours later, she was forced to leave the apartment. “A police patrol had to come and tell them that they couldn’t throw me out,” she says. “But [the landlord] insisted that I go.” Thanks to support from the nursing union Satse, she moved to Colón Hotel, which has been turned into a hospital for coronavirus patients with mild symptoms. She has been staying there ever since. “I felt like it was an attack against the [nursing] collective,” says Serrano. “It seems there was another guy who had the same thing happen to him and was living in his car, with a fever, without a bed to sleep on. Many more arrived later on.”

These actions have been condemned by María Pilar Allué, police commissioner and head of staff at the National Police. “They are hate crimes. They are reportable, reprehensible and prosecutable [offenses],” she said on Tuesday, during the daily press conference on the coronavirus crisis in Spain. The state of alarm, declared in a bid to slow the coronavirus outbreak, has confined most Spaniards to their homes since mid-March. Only essential workers such as doctors, nurses and supermarket cashiers, as well as some non-essential workers, have been allowed to continue going to their workplaces during this period.

A few weeks ago, Elena, a warden at a health center in Alcorcón in the Madrid region, found the door to her home covered in bleach. The 48-year-old suspects that it was the work of a neighbor whom she had clashed with just a few days earlier. “I follow very strict cleaning measures,” she explains by phone. “I take off my shoes, I disinfect them and I have a shower before touching my children.” The day of the argument, Elena had forgotten her boots outside her front door and this infuriated her neighbor, who told her she should be ashamed of herself. “She told me that I was going to infect the whole building, and that I would have to disinfect the stairs and the common doorknobs, every time I came home,” recalls Elena.

Elena never imagined that something like this would happen to her. When the neighbor rang her doorbell, she thought it was to ask her to buy something from the pharmacy or the supermarket, which she had offered to do when the lockdown first came into effect. “They are an elderly couple and they shouldn’t be coming and going,” explains Elena, who says she understands her neighbors’ fear and feelings of helplessness. “What would happen if she decides to take it up a notch and spray me with the bleach instead?” she asks. “This virus is not just a cough. It is bringing to light the darkest side of people.”

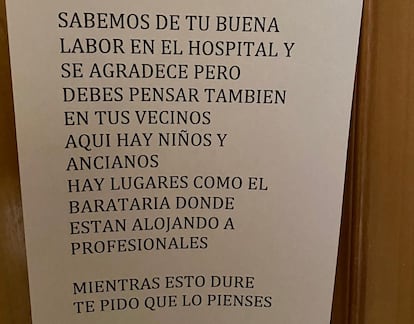

In the case of Jesús, a 28-year-old medical graduate who is doing his residency at the La Mancha general hospital in the province of Ciudad Real, a note was left on his door. It read: “Hello neighbor. We know of your good work at the hospital and it is appreciated, but you also have to think about your neighbors. There are children and seniors here. There are places like [Hotel Ínsula] Barataria [in the town of Alcázar de San Juan] that are housing professionals. While this lasts, I ask that you consider it.” Jesús saw the message when he came home after working 12 hours at the hospital. He was not expecting it. “You arrive exhausted from work, and of course seeing that on my door made me sad,” he says.

Jesús sent a photo of the note, which his mother shared on Facebook. Hours later he was flooded with messages. “I still have messages of support that I have not replied to. They have invited me to dinners, they have put up a sign that says ‘A hero lives here’ on the front door,” says Jesús, who is from Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands. The mayor of Alcázar de San Juan, Rosa Melchor, even went to the hospital on Sunday to hand Jesús a letter of appreciation. “I want that to be what I take away from all this. And to think that the person who wrote [the note] did so out of the fear we all feel,” he says.

Miriam Armero, a supermarket worker from Murcia, was also targeted by her neighbors. They put up a sign with sticky tape on a mirror in the main entrance to the building. It read in capital letters: “We are your neighbors and we want to ask you, for everyone’s sake, to look for another home while this lasts, because we have seen that you work at a supermarket and many people live here. We don’t want any risks. Thank you.” The message, like the one Jesús received, was anonymous. Shortly afterwards, Armero – whom EL PAÍS was unable to reach for comment – put up her own note beside the sign. She asked for “less applause at 8pm, and more empathy for the people who have to work and who have a family,” in reference to the nightly applause for the efforts of essential workers who continue to do their jobs under the coronavirus lockdown.

The supermarket worker also responded to the note in a video she shared on Facebook. In the video, which has been seen more than 700,000 times, an emotional Armero says: “I am not going to leave my home. I know perfectly well what I have to do when I arrive. I am the first to know that I can’t give my son a kiss until I take off my clothes.” She concludes: “We are dealing with enough already with what we go through every day, to have to endure this as well.”

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.