The technology that reveals what happens in 0.00000000000000000000001 second

A Canadian has been awarded for his ultra-fast pulses of light, a compass to discover the microworld

People have the feeling that everything happens very quickly. But normal things in our everyday lives happen extraordinarily slowly compared to the speed of events in the microscopic world. This is a world beyond the limits of human perception where matter is determined, where combinations of particles make up all the substances in the universe. There are events that occur in attoseconds (as), a trillionth of a second. An attosecond is equivalent to 0.000000000000000000001 second or 1x10-18 of a second and corresponds, approximately, to the time it takes light to pass through an atom and the natural scale of electronic motion in matter. The Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO) has also achieved a soft X-ray pulse of just 19.2 attoseconds.

The Hungarian Ferenc Krausz, the Frenchwoman Anne L’Huillier and Frenchman Pierre Agostini were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2023 for developing extremely brief pulses of light to measure the hitherto immeasurable process of the movement or exchange of energy of electrons. They received it eight months after this research obtained the BBVA Foundation’s Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Basic Sciences category.

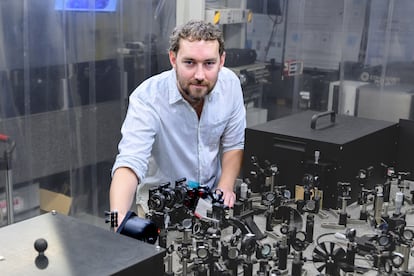

The BBVA Foundation and the Royal Spanish Society of Physics (RSEF) have once again awarded a prize to a researcher in this almost unexplored field whose map, which until this century could only be mapped through theories on paper. The Young Researcher Award in Experimental Physics has gone to Allan Johnson, Ramón y Cajal scientist at IMDEA Nanoscience Institute for his experiments generating ultrafast pulses of light — the compass for discovering a world where what we know begins to take shape, enabling the study of materials, the understanding of the quantum universe, and even the observation of the body’s cells in an unprecedented dimension.

Johnson was born 35 years ago in Ottawa, Canada, where he studied physics and math. After obtaining his doctorate at Imperial College London, he came to Spain on account of his wife, with whom he has two children. “In other places, I have the feeling that life means suffering, that the present is worse than the past. In Spain, I feel that there is a brighter future. It’s a good country to live in,” he says.

He received the award for his work with the so-called overdriven regime, a technology that uses extremely powerful lasers to generate attosecond-long X-ray pulses with which he can measure complex materials. “We used a very high-power laser and focused it to reach such a high intensity that, in the hottest focus, it could reach temperatures higher than those on the Sun’s exterior. You get a superheated plasma that pulls electrons out of atoms and breaks matter,” he explains.

The technology of Johnson’s team is the key to other research. “When we generate plasma with a very powerful laser, it emits an X-ray pulse of one attosecond and it is this emitted pulse that we use for other experiments. The supercharged regime is a way to generate attosecond pulses with X-ray energies in the laboratory. All downstream applications use ultrafast X-rays, but they are not specific to the supercharged regime.”

Among the applications is the understanding of the dynamics of electrons, fundamental in the quantum field, which, according to physics, explains nature: “The correlations between electrons are very important. In a normal material, such as a piece of aluminum or glass, we imagine that each electron functions independently. That’s not entirely true, although we’ve built every semiconductor in the world and computers based on this idea. But in quantum materials, the model doesn’t work like that and that’s why we need to understand how electrons interact.”

To exemplify the importance of these investigations, Johnson explains that 10% of electricity generated is lost along the way. “Reducing these losses can help a lot with the fight against climate change or with Europe’s energy independence,” he explains.

Supercharged regime technologies are also fundamental in metrology and with practical applications in the construction of microprocessors or, as Johnson explains, to “look at cells at a higher resolution than that of any existing optical microscope.”

Another field opened up by these attosecond pulses is materials science. But the field is wide: “On the nanometer scale, we can take materials and turn them into something magnetic or the other way around. There is some work that suggests that we can actually convert a material that is not a superconductor into a superconductor. We can trap materials in very different states than are achieved in other ways.”

The dream, Johnson says, would be to create materials that do not exist in nature with unique properties, on demand. But he recognizes that we are still a long way off. However, he believes that the path is open and that there are already feasible applications in information processing, sensors, space technology and neuromorphic computing, that mimic the human brain.

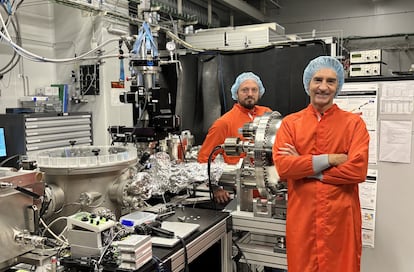

ICFO record

In the same field, a group of researchers from the Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO) has set a new record by generating the soft X-ray pulse of only 19.2 attoseconds, considered the shortest to date. This is the fastest flash of light, even faster than the atomic unit of time (24.2 attoseconds), which corresponds to the time it takes for an electron to complete an orbit around the hydrogen atom: the “atomic year,” reports the ICFO in a note based on the research published in Ultrafast Science.

“This new capability paves the way for advances in physics, chemistry, biology and quantum science, enabling direct observation of processes that drive photovoltaics, catalysis, correlated materials and emerging quantum devices,” says ICFO German physicist Jens Biegert.

The institute explains that the key to these findings is understanding how matter behaves and interacts at atomic and subatomic scales: “Electrons determine everything: how chemical reactions develop, how materials conduct electricity, how biological molecules transfer energy, and how quantum technologies operate. But the electronic dynamics occur on attosecond timescales, too fast for conventional measurement tools.”

“Our results demonstrate the remarkable capabilities of attosecond technology and lay the groundwork for its widespread use in fundamental and applied science,” the scientists conclude in their study, where they note a similar achievement — though in a different range — published in the journal arXiv.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.