Sally Ride, the pioneering astronaut who had to hide her sexual orientation

The documentary ‘Sally’ revisits the story of the first American woman to go into space and the hurdles she faced back on Earth

“Oh, by the way, Sally Ride was gay.” This was the headline in a New York Magazine obituary noting the death of America’s first woman astronaut on July 23, 2012. The headline was meant to emphasize the low-key, casual way in which the world learned both that the space pioneer had died of pancreatic cancer, and that she was lesbian. A press release, carefully crafted by Ride and her partner, only mentioned in passing “Tam O’Shaughnessy, her partner for 27 years,” but it became almost bigger news in the U.S. than the death of Ride, who became the first American woman to travel to space in 1983 — a milestone Valentina Tereshkova achieved for the USSR in 1963.

On June 17, National Geographic will release a documentary called Sally on Disney+ that revisits her story and the double difficulty she faced in achieving her feat: reaching space as a woman and a lesbian in an era as sexist as it was homophobic. By reviewing her hardships, the documentary challenges today’s society at a time when many people — like Donald Trump, who is purging diversity at NASA — seem to want to erase all traces of diversity and the empowerment of minorities on their path to true equality.

“Every kid dreamed of being an astronaut at some point, but since the space program was all-male, it never even occurred to me that I could be one,” Ride begins in the film, which is constructed from footage from her time at the space agency and current accounts from people who were close to her, like her widow Tam O’Shaughnessy.

Fortunately, in 1976, NASA opened its doors to the first class that accepted women and racial minorities, and Ride, born in Los Angeles in 1951, didn’t hesitate to apply. She was an astrophysicist at Stanford University and an amateur tennis player with the chops to have been a professional, in case anyone was wondering about meritocracy. In the presentation of that class of 35 candidates, only 10 got all the spotlight and hours of excruciating press questions: the six women, three Black men, and one of Asian descent. They got the worst of it.

“They didn’t want to know about our hopes for space exploration or what we wanted to do. They took the stereotypical perspective: the romance, the makeup, the fashion... The perspective they usually used when reporting on women,” recalls one of the candidates from that group, Kathy Sullivan.

“The only bad moments during training had to do with the press,” Ride recalls. And it’s easy to believe, given the pitiful questions she and her colleagues were asked in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Questions about motherhood, pregnancy, or whether she “weeps” under pressure — and this was even before she was about to fly into space.

As the documentary clearly shows, these women wanted to fit in with the program, but at the same time, they were brave and successful professionals who didn’t flinch when it came to standing up to the sexism of the time. “You shouldn’t even ask that question, just delete it,” Judith Resnik tells a reporter. “Either call me Dr. Ride or Sally,” the astronaut tells another reporter, who calls her “Miss Ride.”

Competitive and ambitious, like anyone aspiring to go into space, Ride knew just what to say in front of the cameras to avoid making a fool of herself. “Are there people at NASA who are still unconvinced that women have a place in the space program?” she was asked. “I think there are some people who are just waiting to see how I do. Let me put it that way.”

But the truth is that the pressure was at its highest at the Johnson Space Center, where there were 4,000 men and four women. A place named in honor of Lyndon Johnson, the man who nipped the Mercury program in the bud in the 1960s, which aimed to train female astronauts at the dawn of the space race. The race the Soviets won four times with Sputnik, Laika, Yuri Gagarin, and Tereshkova. And also with Svetlana Savitskaya, the second woman in space, in 1982.

NASA’s “man culture” was on display in a now-legendary episode, narrated by Ride herself in the documentary. She was the first woman to check what they called “crew equipment,” the space toiletries bag. They already knew what to pack in the men’s, but what to pack in hers? “In their infinite wisdom, NASA engineers designed a makeup case,” Ride says bluntly: little pockets for lipstick, eyeliner, makeup remover... “Then they asked how many tampons they should carry on a week-long flight. ‘Is 100 the right number?’ I told them no, it wasn’t the right number.”

“Sally grabs one of those toiletry bags, a canvas bag with zippers, and keeps pulling out tampons like those funny snakes that jump out in party tricks,” Sullivan recalls. “The six of us together, in half a year, wouldn’t have used all the tampons in there.”

When Sally’s mother was asked to comment on the historic change that had allowed her daughter to become an astronaut, she exclaimed, “God bless Gloria Steinem!” referring to the historic feminist, who also attended her launch into space in 1983 as a VIP.

But Ride was above all discreet, defending her place as a woman without openly declaring herself a feminist (although she did have a historic conversation with Steinem). Upon returning to Earth, as the most famous woman in the world, she felt anxiety, the weight of being a role model — “women cried when they saw me” — and had to go to therapy to deal with it.

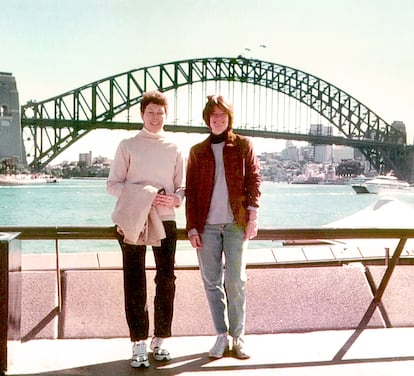

She met Tam during tennis lessons as a teenager, and they developed a close friendship that blossomed into true love in 1985, shortly after Sally returned from space. In 1982, before being selected for the mission, she had married a classmate, Steven Hawley, who also appears in the documentary acknowledging: “We were more like roommates than life partners.” Ride divorced her husband and left NASA in 1987, after discovering, following the Challenger accident (in which her friend Resnik died) that the agency wasn’t doing everything it should have to protect its crew.

The astronaut concealed her homosexuality until her death — “she was afraid, and it breaks my heart,” her widow now says — and she had good reason to do so. Her friend and famous tennis player Billy Jean King explains the exemplary impact it must have had on Ride when she herself was dragged down the walk of shame in the early 1980s after it emerged that she was a lesbian, a fact that lost her public favor and millions in contracts.

At the end of the documentary, a friend of Ride’s laments: “I found out almost at the same time as the rest of the world: when I read her obituary. I was saddened that society could make someone we admire, love, and respect feel like she had to hide something about herself.”

“Sally had to repress a large part of her identity in order to break the highest glass ceiling,” says Cristina Costantini, the documentary’s screenwriter and director, who warns, citing the current Trump administration, that “many of our hard-won rights are once again under threat.” A few weeks ago, NASA removed from its website the stated intention of having a woman step on the Moon on the next manned trip to the satellite, eliminating the last remaining glass ceiling for female astronauts. Until the next Sally Ride manages to break it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.