Success or failure? Almost out of battery, two frozen spacecraft landed sideways on the moon

After taking advantage of their modest budgets, the Japanese ‘SLIM’ and the U.S. ‘Odysseus’ modules landed on the satellite with difficulty

It is taking a lot of effort to land on the moon again after doing so over a half century ago. Of the last six attempts, only one — the Indian probe Chandrayaan-3 — was successful. For one reason or another, the other efforts cannot be considered successes. But have they been disasters?

Undoubtedly, three missions did indeed end in disaster. First, there was the Japanese Hakuto-R, whose altimeter was confused by the abruptness of the landscape and kept it hovering at three miles altitude until it ran out of fuel. That was followed by the Russian Luna 25, which crashed when it failed to shut down its engine in time, meaning it fired longer than it should have. This accident occurred as it attempted to beat India to make the first lunar landing at the Selenite south pole. Then came the Peregrine, a private project with a NASA grant, which failed to close a valve injecting gas into the fuel tank to bring it under pressure. The tank cracked and its contents were lost to space. Without auxiliary propulsion, it failed to reach the moon and fell back to Earth.

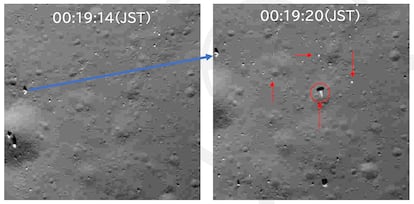

In January this year, Japan tried again with SLIM, an experimental vehicle solely intended to test precision lunar landings. The operation appeared to have gone well, including the launch of two tiny robots equipped with television cameras just before touchdown. But something went wrong, which became apparent when one of the robots transmitted a photo of SLIM, perched on its nose on the ground. Its solar panel, intended to point east to take advantage of the sun, was facing west and was not generating power.

Telemetry and then an image obtained during the descent confirmed the reason for the failure. At 164 feet altitude, the nozzle of one of the two braking motors had detached and fallen to the ground. With its momentum unbalanced, the SLIM began to somersault as its guidance system struggled to stabilize it. It landed under these conditions.

It is a testament to the skill of the Japanese engineers (and the impact of low lunar gravity) that the probe reached the ground in one piece. For the sake of comparison, it was like a car losing a front wheel while speeding down the freeway. Not only did the landing software manage to slow down sufficiently, but it brought SLIM to within 196.85 feet of the intended landing spot; had it not been for the malfunction, it would have landed ten times closer.

On the moon, the sun rises and sets as it does on Earth, but the day, from sunrise to sunset, lasts for two weeks. It only had to wait until noon for the solar panel to receive light again and for communications to resume. SLIM had no heaters, so no one expected it to survive the frigid lunar night. But to everyone’s surprise, as dawn broke, it began transmitting again. Somewhat harshly, JAXA, the Japanese space agency, gives itself a score of 60 out of 100, for this first attempt. Right now, both SLIM and the U.S. Odysseus are preparing for another night in the hope of waking up.

The ‘Odysseus’ misstep

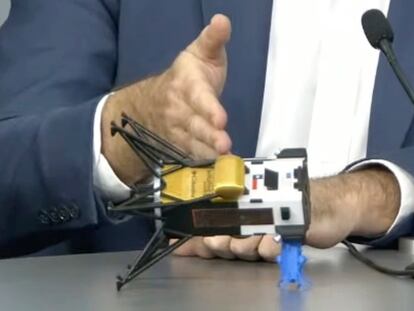

As is well known, the last mission to the moon was made in February by Intuitive Machines, another private company under contract with NASA. It was the Odysseus that carried six technological experiments and as many commercial cargoes on board, including a Jeff Koons sculpture composed of a hundred metallic spheres reproducing the moon in its different phases.

Odysseus’s journey did not pose any problems until shortly before the landing phase. The flight controllers noticed that the laser altimeter was not working: it was still in test mode, and no one had removed the shields used to prevent a technician from being blinded accidentally during pre-launch tests.

With the altimeter disabled, it was impossible to land. The technicians were forced to improvise an emergency solution, taking advantage of one of the loads supplied by NASA, which also contained a LIDAR and would serve, precisely, to measure distance and descent speed, although it was experimental equipment.

The landing, under improvised automatic control, was almost normal until the last moment. It touched down at 6 miles per hour, but with a remaining horizontal speed of 1.86 miles per hour, similar to that of a pedestrian. That was the cause of the failure. As it slid over the ground, a leg tripped over a hollow or a rock and the craft stumbled and turned over.

Purely by chance, almost all the loads installed on the outside of the ship were left on top or on the sides, as were the solar panels. The only one that ended up underneath, perhaps crushed, was Koons’s sculpture, anchored to one of the sides. The artist was delighted to learn that his work would be even closer to the moon.

Before its power was depleted, Odysseus completed a fitting farewell transmission. Received today, this image from February 22nd showcases the crescent Earth in the backdrop, a subtle reminder of humanity’s presence in the universe.

— Intuitive Machines (@Int_Machines) February 29, 2024

Goodnight, Odie. We hope to hear from you… pic.twitter.com/RwOWsH1TSz

The altimeter’s failure prevented the launch of a camera that should have filmed the landing, although there is still hope that it can be ejected later to at least get a view of what Odysseus looked like. Some experiments will work even with the spacecraft lying down. But for now, the biggest danger is the cold. On February 29, night fell over the Malapert crater where the rover is located.

Tight budgets

Were moon landings more reliable half a century ago? The Russians tried half a dozen times before succeeding with a capsule much smaller and simpler than the current ones. The Americans didn’t get their first pictures of the surface until the seventh attempt; in fact, the Ranger program was nearly cancelled due to a string of failures. Automatic landings failed in two of their seven pre-Apollo launches.

The landing cannot be directed from Earth. The nearly 248,548.5 miles of distance to the moon means there is a delay of almost three seconds. By the time the warning that a spacecraft is in trouble reaches Earth, it would have already shattered into a new crater a second before.

For the companies that are designing them, the current programs are once again initial tests, and it is normal to expect difficulties. If landing on the moon seemed easy 50 years ago, it is because humans were at the controls of the Apollo missions. Now, as long as everything goes as planned, a computer can direct the maneuver with robot-like precision; but when something unexpected happens, two eyes, a brain and the ability to improvise usually give better results.

Moreover, let’s not forget that, because these are commercial programs, budgets are much tighter than the funding that was available to NASA during its race against the Soviet Union, when the most important thing was to win at any cost. The Surveyor program (NASA’s first automated spacecraft to land on the moon) cost $5 billion in today’s dollars. It is estimated that building a similar vehicle would cost between $500 million and $1 billion today.

By contrast, Intuitive Machines has invested some $250 million in the project. As a customer for these transport services, NASA has contributed less than half. Even cheaper were the Japanese SLIM, which cost $121 million; the failed Peregrino and Berasheet, which cost $100 million each; and the Hakuto-R, which was less than $90 million.

Many companies are investing in the moon as a new and emerging business sector. But getting there is difficult. And expensive.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.