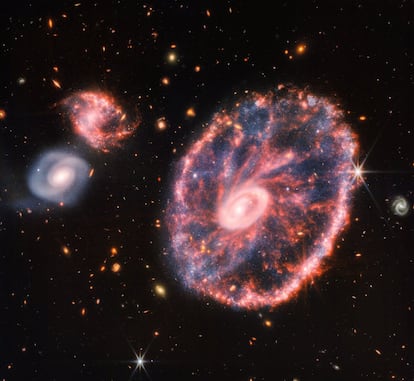

Galaxies are only 100 years old

It has been a century since the event that led to the discovery that the Milky Way is not the only galaxy in the universe

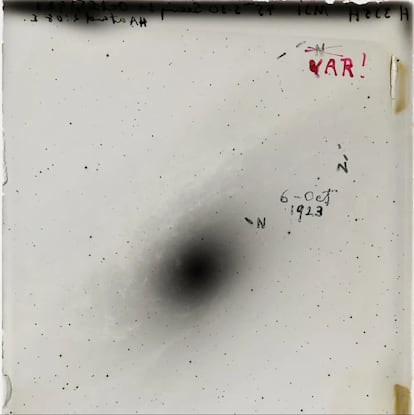

One hundred years ago, on the night between October 5 and 6, 1923, humans became aware of galaxies for the first time. That was when Edwin Hubble took a picture of what he called the Messier 31 nebula, which we now know better as Andromeda. Most astrophysicists don’t like the word photo and prefer to talk about images of the sky, but Hubble actually used a photographic plate. The plate with which he made the famous photograph measured about 10x13 cm², took data for 45 minutes through the 100-inch Hooker telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory, in what is now a heavily light-polluted part of Los Angeles. We can think of that photographic plate, called H335H — the Hooker plate 335 taken by Hubble — as the birth certificate we humans created for all galaxies, the first record of their existence.

That image isn’t well known but it should be iconic, including Hubble’s inscription in red on it: he wrote “VAR!” and crossed out an “N” next to a star. Initially, he had identified a small object visible in the photo as a nova, a star that would have randomly and briefly increased in brightness, then faded out and become quite a bit fainter again. But that night, Hubble, to his surprise (judging by his exclamation point), discovered that the star’s brightness varied periodically.

That was exactly what he was looking for. On that autumn night in 1923, over three years had already passed since the so-called Great Debate, which discussed whether the Milky Way was the entirety of the universe or there could be other places similar to the Milky Way, other... at that time, there was no word for what we know today as galaxies! There were two options discussed in the Great Debate. One said that what were known as spiral nebulae — such as the Messier 31 (mentioned in the first paragraph of this article), which had been known by that name since the late 18th century when Charles Messier published his Catalogue of Nebulae and Star Clusters — were part of our Milky Way. The other possibility was that they were other similar objects, beyond the limits of our home. In that debate, arguments for both possibilities were advanced, but the option that was proven wrong three years later, that the universe was limited to the size of our Milky Way, won at the time. Science sometimes takes a step backward in order to leap forward. Note that I had a hard time not writing galaxy in this paragraph, but the word did not exist as we know it today, and the Great Debate did not bode well for that word.

Hubble must not have been very convinced by the conclusion of the Great Debate, because he kept trying to answer a question so basic (yet fundamental) that it seems to have been asked by a child: how big is the universe? And to find the answer, he was looking for a type of star that had been discovered, some 10 years after Messier built his catalog, in 1784, and periodically varied in brightness. Over a century later, in 1908, science slowly advanced: the astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered that these stars’ period of variability depended on their luminosity. These stars are known as Cepheids, because the first one (well, today we believe it was the second) discovered was the fourth brightest star in the constellation Cepheus, named for Andromeda’s father (what a coincidence!). Hence, its name is Delta Cephei and it is the qualifier for such stars, the Cepheids.

Hubble knew that this great property of the cepheids that the universe gave us could be used to determine the distance to distant objects. We only needed to look for Cepheids, study their variability, determine their period (all of which requires a lot of patience and the help of human computers), and we can use that to calculate their intrinsic power (the energy they release per second). We astrophysicists call that luminosity (because there is a lot of history in astrophysics, and we are reluctant to use the proper physical word: power). By comparing that power with the light we receive, we could calculate the distance. It is enough to use the physical-mathematical description of the very obvious property that lighthouses, no matter how bright and blinding they may be when seen up close, become dimmer at greater distances.

Today, we can say that, on the night of October 5-6, 1923, Hubble discovered the vastness of the universe with that great goal in mind. With his observations from that night and several others in the weeks that followed, Hubble calculated the distance to Andromeda to be about 2 million light-years. The Great Debate discussed Milky Way sizes of between 30,000 and 300,000 light-years, so Hubble’s calculation was beyond reproach: that star, known today as V1 (and observed by the Hubble telescope 80 years later), which surely belonged to the Andromeda nebula, was much, much farther away than the confines of the Milky Way. Moreover, at that distance and taking into account the size of the nebula in the sky by using another physical-mathematical equation that says that distant objects appear smaller than they are (something that, in general, is a lie, but that is another story), it could be calculated that Andromeda’s size was similar to that of the Milky Way.

The many other nebulae known at that time were at distances as great as or greater than those 2 million light-years, which Hubble and other astronomers measured in successive years. It matters little that Hubble’s distances were wrong by a factor of 2. The numbers were so large that one could only conclude that there were other Milky Ways, other... galaxies. That was the birth of a new term, a new branch of science, a whole new conception of the universe. On that night 100 years ago, we took the data to learn that the cosmos is gigantic, its size changed for us forever in the blink of a camera shutter (which was 45 minutes). We were also on the doorstep of a paradigm shift in how we conceive the cosmos, which we would soon discover to be expanding, also because of that “VAR! plate” and the first Cepheid in M31 that Hubble discovered 100 years ago. From that moment on, the universe was never the same.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.