A fossil leg bone may reveal the oldest case of cannibalism, from 1.45 million years ago

American paleoanthropologists found cut marks on a human tibia stored in a museum for decades

American paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner is an expert in studying the diet of extinct hominids. One day, as she looked for traces of animal bites on a fossil tibia from 1.45 million years ago, she noticed something peculiar. The bone, found in Kenya in the 1970s and stored in the Kenyan National Museum, had several straight, parallel marks at one end that could not have been made by the teeth of any animal. Today, Pobiner and other colleagues argue that this could be the oldest known case of human cannibalism.

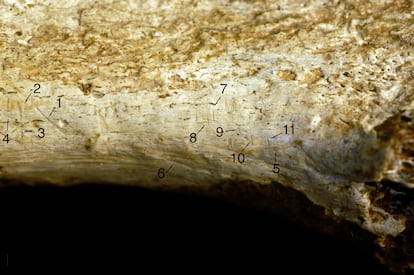

When Pobiner found the cuts, she made a mold with a paste similar to the one dentists use to reproduce their patients’ teeth and sent it to Michael Pante, at the Colorado State University. She gave him no clue about what the marks might be. Pante studied them, comparing them to nearly 900 bone indentations made in defleshing and quartering experiments. The verdict of the researchers is that these marks had to be made by a hominid using a sharp stone tool, probably to cut the meat and eat it, as explained in a study published today in Scientific Reports.

“Both modern humans and our ancestors have practiced cannibalism; this finding shows us how old this practice is,” explains Pobiner, a researcher at the Smithsonian Institution, to EL PAÍS.

The fossil could not be attributed to a specific species with absolute certainty. It could have been a Homo habilis, which was a hominid capable of making tools, or a Paranthropus boisei, a more primitive hominid characteristic for its powerful jaws.

It is also impossible to know if the case occurred between two members of the same species, which would make it cannibalism, or by different types of hominids, which would make it a case of hunting or scavenging. Despite these uncertainties, scientists believe that the most plausible explanation is that these early humans were eating each other; the oldest of which there is evidence. In the study, the specialists argue that it is not very likely that the marks were made after the find (when handling it in the museum, for example), as the indentations would show a different color.

Up to now, the oldest case of hominids eating members of their own species is that of 10 individuals, most of them children and teenagers, who were murdered, dismembered, defleshed and eaten by their peers some 900,000 years ago in the Sierra de Atapuerca, in Burgos, Spain. In this case, the evidence of cannibalism is much clearer, explains Palmira Saladié from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology. “The bones show many cut marks, as well as breaks in the long bones to consume the marrow and the skull to reach the brain,” she describes. The researchers of this site believe that these infanticides were the result of a war between opposing groups that competed for the prey and the resources of the mountains. The weakest individuals were attacked, killed and eaten; but not out of hunger, because at the site, along with the human fossils, animal bones were also found. For paleoanthropologists, this is what marks the difference between “dietary” cannibalism (when humans are part of the diet of other humans) and “ritual or war” cannibalism, explains Saladié. “These behaviors are very similar to those currently observed between opposing groups of chimpanzees,” she adds. The American researchers believe that the butchering case of Kenya was solely motivated by the need for food.

Throughout human evolution, cannibalism happened sporadically, taking on diverse forms. For example, there is a sort of affectionate cannibalism, which occurs when members of a clan eat the remains of a loved one so that they do not rot and as a gesture of respect. At the other end of the spectrum, cannibalism can occur when an enemy is devoured to inflict the ultimate humiliation: being transformed into feces. In Atapuerca, they have found abundant traces of a common ritual before and after the Neolithic Revolution, some 8,000 years ago, in which the skull is used as a cup.

For the paleoanthropologist, the Kenyan find is probably genuine and represents a case of cannibalism, although more remains will be needed to prove it. “We always found it strange that there were no signs of cannibalism among the hominids of Africa, when there is so much later evidence, from the Homo antecessor of Atapuerca to the Homo sapiens, including the Neanderthals,” she points out. “Cannibalism is difficult to prove with only one bone, but it is the most likely explanation,” adds Saladié.

The Kenyan bone has a second set of marks that make its story more interesting: feline bites. “The bite marks suggest initial access by a lion that consumed the main muscle mass, and the hominids subsequently scavenged the small remains of meat that were left at the end of the tibia, but they didn’t fracture it to consume the marrow. It’s fascinating,” emphasizes Antonio Rodríguez-Hidalgo, a researcher in Atapuerca.

There is another enigma presented by the fossil. The bone was found in 1970 by the famous paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey at the Koobi Fora site. Three years later, it was analyzed by her American colleague Anna Behrensmeyer. “I am intrigued by how Behrensmeyer interpreted these marks when she studied the remnant in 1973, because she is one of the main figures in taphonomy [the part of paleontology that studies processes of fossilization] in the world,” says Rodríguez-Hidalgo. “Although she described all the modifications that we see in the photographs, she did not identify these small transverse marks that are now considered to be deliberate cuts made to consume the meat.”

The Kenyan case joins two other human remains found in Africa that show inconclusive traces of cannibalism: the skulls of Bodo (Ethiopia) and Sterkfontein (South Africa). Still, for Hernández, neither instance has conclusive evidence yet. “This case is not indisputable, but I think that at some point more remains will be found, as cannibalism seems inherent to human evolution, and after all, the oldest deposits are in Africa. For now, the case of Atapuerca continues to be the oldest solid evidence of cannibalism in human history,” she concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.