Scientists eye mission to Uranus: an alien world where the darkness of winter lasts 21 years

The US and Europe face the challenge of sending probes to the most unknown planet in the solar system by 2050

The scientific community agrees that the largest space exploration mission of the decade must begin now. And scientists opine that the destination should be Uranus – the strangest and most unknown planet in the solar system.

Most of what we know about this world – which is four times the size of Earth – comes from photos taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, which passed the planet on its way to the fringes of the solar system more than 30 years ago.

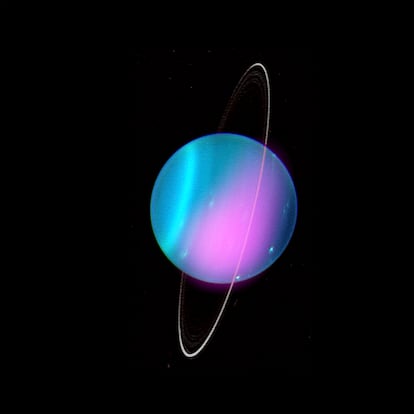

The images revealed an intense blue world that rotates on its side – unlike the rest of the planets – as if it were a ball rolling on the ground. Uranus makes a complete orbit around the Sun every 84 Earth years. And winter on the planet lasts for 21 years, with temperatures reaching -371 degrees F.

Over the course of a few hours, Voyager 2 was able to observe some of the 27 moons and 13 nearly-vertical rings that surround the planet. On the surface of Ariel – the youngest of all the moons of Uranus – there were fresh scars, suggesting that, beneath the ice, there is an ocean where life could exist.

A large panel of experts assembled by the National Academy of Sciences of the United States recently met to set the scientific priorities for this decade. The panel has concluded that the next great mission that NASA should approve by 2024 is to send a probe to Uranus – one that can penetrate its unknown atmosphere – and another spacecraft that can orbit the planet for at least five (Earth) years. No other robotic mission, the panel argues, will be able to generate more scientific knowledge. The budget could exceed $2 billion.

On February 16, Kathleen Mandt of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory explained in an article for the journal Science that this mission “will be able to clarify the origin and evolution of the solar system, as well as explain the phenomena that occur only on the mysterious Uranus.”

The probe duo could tell us how the seventh planet formed, when it migrated from the center of the nascent solar system to its current position, as well as why it spins in the way that it does. It’s possible that, about four billion years ago, the planet collided with another world the size of Earth. The cataclysm literally turned it inside out, but failed to disintegrate it; this would explain its current rotation.

Uranus may seem like a strange planet, but the truth is that Earth is the strange one. The vast majority of the 5,000 planets beyond the solar system that have been discovered to date are “super-Earths” the size of Uranus and Neptune. Understanding them means understanding a good part of the universe.

4.5 billion years ago, the giant planets formed from gas and rocks in the planetary nebula surrounding the Sun. The gas giants – Jupiter and Saturn – mostly formed from the lighter elements (hydrogen and helium). Meanwhile, the ice giants – Uranus and Neptune – hosted heavier compounds, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and sulfur. All the giants migrated from the center of the universe to their present position.

The rocky planets – Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars – were formed from the leftover materials that the giants didn’t carry with them. Knowing the abundance of chemical elements in Uranus’s atmosphere is essential to understanding exactly how everything occurred over a period of billions of years, particularly the chapter in which water and other compounds essential for life arrived on Earth.

In recent years, neither Jupiter nor Saturn has been found to harbor solid interiors. Mandt explains that they’re rather diffuse, mixed with the gaseous atmosphere that surrounds them. The future atmospheric probe and the Uranus orbiter would be able to determine whether or not there is a hard heart of rock and ice inside the planet.

The mission will also be key to mapping Ariel, Miranda, Titania, Oberon and Umbriel – the planet’s five main moons – which could be ocean worlds with large amounts of liquid water. Another of the planet’s mysteries is why nine of its very thin rings have not disintegrated. The possible answer is that there are still undiscovered shepherd moons, whose gravity holds the herd of rock and ice together.

With current technology, it would take a space probe 12 to 15 years to cover the 1.8 billion miles to reach Uranus, so long as it can use Jupiter’s gravitational pull. This constricts the launch possibilities. If humanity wants to reach this planet before 2050 – when the fall equinox in the northern hemisphere will hide part of its most interesting moons – we must get down to work now. Ideally, Mandt notes, NASA will approve the mission in 2024 and it will be launched by 2032. This would leave enough time for such an ambitious mission to be designed.

Fabio Favata, coordinator of scientific programs at the European Space Agency (ESA), tells EL PAÍS that Europe’s collaboration will be essential for this mission. The ESA has been studying possible trips to Uranus for several years and has mastered key technologies to be used on the planet, such as magnetometers, which can study the magnetic field and reveal its interior.

“One of the big challenges is that we cannot use solar panels on Uranus, because it’s too far from the Sun. New nuclear fuel reactors will probably have to be developed,” he explains.

According to the astrophysicist, “NASA still has many mission options on the table. A decision must be made no later than 2024 to be able to launch – at the latest – in the middle of the next decade.”

Beyond Uranus, perhaps the next big mission (in two decades) would be Neptune: the other ice giant that is an equally unknown world. Pluto, on the other hand – which is even farther away and is no longer considered a planet – is much better understood, thanks to a visit made by NASA’s New Horizons probe.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.