Zombie fires and soaring temperatures: What happens when it gets to 100ºF in Siberia

Satellite data shows that blazes swept through nearly 12 million acres in the Siberian Arctic between 2019 and 2020, resulting in unprecedented carbon dioxide emissions

In the Russian town of Verkhoyansk, in the region of Siberia, everybody was once so used to the cold that kids would only skip school when the temperature hit -58°F (-50ºC).

This changed in June 2020, when a heatwave ticked the thermometer up to 100ºF (38ºC). It was the hottest temperature ever recorded north of the Arctic Circle. The icy terrain – once used as a gulag by Russian dictator Joseph Stalin to punish dissidents – suddenly began to resemble a Mediterranean beach.

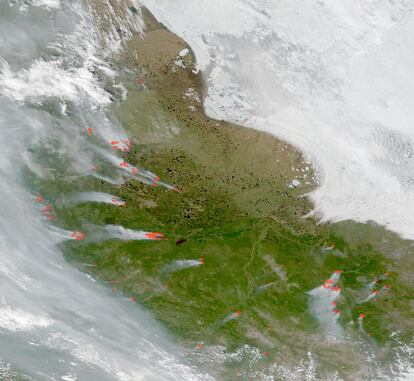

An international team of scientists is now revealing the exact consequences of that thermal anomaly. For instance, as ice melted across the area, wildfires were able to rage unchecked in the Siberian Arctic, destroying nearly eight million acres of forest – an area the size of Belgium. The carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions produced by the fires equaled Spain’s annual output. In the end, Putin had to mobilize his army to calm the flames.

The researchers – led by Spanish ecologists Josep Peñuelas and Adrià Descals, from the Barcelona-based Center for Research on Ecology and Forestry Applications (CREAF) – have analyzed four decades of satellite data. Arctic forest fires are common, but the magnitude of the ones from 2020 had never been seen before. The data shows that the total amount of land burned in the region that year was seven-times the average of the previous four decades.

Peñuelas and Descals found that the gradual increase in global temperature causes a linear increase in scorched surface area, but with the intense rise in temperatures north of the Arctic Circle, the effect is “almost exponential.” Their results were published on November 3, 2022, in Science, one of the world’s leading academic journals.

The Arctic is one of the regions most heavily impacted by global warming. While the average temperature on earth has increased by 0.8 degrees since the 19th century, in the Arctic, temperatures have risen by about five degrees just since the 1970s. The future is even more alarming: forecasts from the Arctic Council suggest that the average air temperature in the Arctic will rise by several degrees between now and the year 2100.

Opposition to any change in direction is strong. According to a report by the British organization InfluenceMap, five of the world’s largest oil companies – ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, BP and Total – spend about $200 million a year on marketing campaigns devoted to “greenwashing” and millions more combatting legislation that aims to reduce CO₂ emissions.

Peñuelas describes a vicious cycle. High temperatures make plants consume more water, meaning that the soil dries out quickly. Lightning from storms ignites massive fires that ravage dry trees, but also arctic soil, where peat predominates: partially decomposed vegetation, often used for domestic heating. Enormous amounts of CO₂ are emitted by the burning trees and peat, which then leads to temperatures rising even further.

“We expected this to happen, with the same frequency and intensity, but we thought it would happen several decades from now. This doesn’t mean that [the fires] will happen every year… yet it’s almost certain that this will soon become more and more frequent. We’re very concerned,” warns Peñuelas.

Satellite data shows that fires swept through nearly 12 million acres in the Siberian Arctic between 2019 and 2020 – an area the size of the Dominican Republic. That’s almost half of the total burned in the entire 1982-2020 period. Arctic fires are so devastating that they can smolder underground for the winter and reignite the following summer. The scientific community has coined an illustrative term for this phenomenon: zombie fires.

Peñuelas is one of the world’s most renowned ecologists, with papers published in major scientific journals. However, he’s a very cautious person – vandalizing paintings by Monet and Van Gogh isn’t his style. He prefers the approach of sharing information, to help everyone understand the magnitude of climate change and the urgency of finding solutions.

“We’re facing a really serious problem. We need to change the way in which we use the planet’s resources. We keep using them as if they’re unlimited,” he sighs.

“We stopped the world because of Covid, but climate change can kill more people and cause more suffering than the pandemic. It may not happen from one day to the next, but the day after tomorrow isn’t far away. We simply must decarbonize the activity of human society.”

The researcher stresses that the increase in megafires is not exclusive to Siberia, but has also been observed in California, Australia, Spain and other Mediterranean countries. CO₂ emissions from combustion fortify the greenhouse effect and raise temperatures, which in turn leads to more fires.

“It’s strange to see this phenomenon in the Arctic. We thought it wasn’t going to happen there,” explains Peñuelas.

The Siberian Arctic represents 70% of all Arctic land. In an article recently published in Science, US ecologists Eric Post and Michelle Mack – from the University of California at Davis and Northern Arizona University respectively – warn that current predictions about global warming do not take into account the vicious cycle that Peñuelas explains: “The enormous release of CO₂ from the Siberian fires demonstrates how quickly northern ecosystems can go from being carbon-absorbing sinks to carbon-emitting sources.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.