Mosquitoes have unique ability to sniff out humans, new study finds

A team of US researchers has discovered that female ‘Aedes aegypti’ mosquitoes, unlike other animals, have multiple receptors in their olfactory neurons that provide them with a sophisticated and ‘unbreakable’ attraction to humans

A question we ask ourselves every summer, in vain: Why is it so hard – even impossible – to escape the ruthless detection of mosquitoes? Often accompanied by another question: Why do they bite me more than everyone else? Scientists and insect repellent manufacturers have known for some time that carbon dioxide (CO₂), exhaled when breathing, and octanol, a volatile compound present in sweat, form airborne highways that mosquitoes use to lead them to their victims. What scientists didn’t know, but have now discovered, is that mosquitoes, unlike other creatures in the animal kingdom, have multiple odor and taste receptors in each of their thousands of olfactory neurons.

In 2004, researchers Richard Axel and Linda Buck won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for discoveries relating to “odorant receptors and the organization of the olfactory system.” A decade earlier, Axel and Buck had found that there are roughly 1,000 genes involved in the process of smelling, which are responsible for a similar number of olfactory receptors. Their work also showed that each olfactory sensory neuron expresses only one of these receptors – a phenomenon called the “one‐neuron‐one‐receptor” rule – and that this information is then sent as an electrical signal to the olfactory bulb, the part of the mammalian brain that processes and interprets aromas. But according to Leslie Vosshall, head of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior at Rockefeller University in New York and a former postdoc in Axel’s lab, “all the Buck and Axel rules were thrown in the garbage can by mosquitoes.”

Vosshall directs a research program aimed at understanding the olfactory system of mosquitoes. Specifically, her work focuses on the mosquito species Aedes aegypti, commonly known as the “dengue mosquito” for its role in spreading the virus that causes dengue fever. But Aedes aegypti is not only responsible for transmitting dengue – their bites can also introduce pathogens that cause yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika, and Mayaro virus disease. Figuring out how to block the odor receptors of Aedes aegypti females – the ones who bite – could have major implications for global health and the prevention of disease.

The latest research findings from Vosshall and her colleagues, published in the scientific journal Cell, show that mosquitoes, like all other animals, have some neurons with only a single olfactory receptor. But they also found that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes have many neurons co-expressing multiple receptor genes. “If you’re a human and you lose a single odorant receptor, all of the neurons that express that receptor will lose the ability to smell that smell,” Vosshall says. “You need to work harder to break mosquitoes because getting rid of a single receptor has no effect. Any future attempts to control mosquitoes by repellents or anything else has to take into account how unbreakable their attraction is to us.”

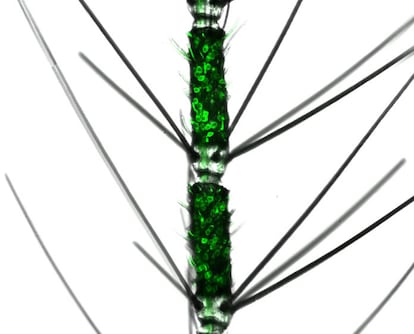

Once the mosquito genome was sequenced and the genes expressing the olfactory receptors were identified, researchers used various techniques to trace the genes and locate them within the individual neurons. Using the modern gene-editing technique known as CRISPR, they were able to introduce different-colored fluorescent proteins that corresponded to different receptors, which then allowed them to see many neurons had more than one active receptor. Vosshall’s team found that neurons stimulated by the human odor octenol were also activated by other ammonia-derived chemicals, or amines, which likewise functioned to attract the mosquitoes.

“Surprisingly, the neurons for detecting humans through 1-octen-3-ol and amine receptors were not separate populations,” explains Meg Younger, a researcher at Boston University and a coauthor of the study. In an email to EL PAÍS, Rockefeller University researcher Margo Herre, the lead author of the study, added: “Mosquitoes also use decanal and undecanal aldehydes [volatile chemical compounds] and more research is needed to determine the exact composition of human odors and which of these odors mosquitoes are able to detect.”

The bigger picture these findings paint is that Ae. aegypti have a double or triple redundancy system – that is, if they fail to perceive one scent, they move on to detect a second or third scent. And if they detect all of them, the signal is amplified. As Vosshall explains: “Mosquitoes have Plan B after Plan B after Plan B. To me, the system is unbreakable.”

The findings could have far-reaching implications. On the one hand, they might help explain why repeated attempts to control mosquitoes and limit their role in spreading pathogens have all ended more or less in failure. As Younger explains, female Ae. aegypti are hematophagous (blood-feeders) “because they need the proteins present in blood to mature their eggs.” The eagerness and sophisticated ability of mosquitoes to bite is the product of millions of years of evolution.

Thus far, attempts to block the olfactory receptors of mosquitoes through genetic modification have failed, perhaps because they all began from the commonly accepted idea – disproven by the new findings – that a given gene expressed only one receptor for each type of neuron. This would also explain the relative, but not total, efficacy of DEET, the repellent discovered by the U.S. military in 1946 that is still the main active ingredient in the vast majority of chemical insect repellents. While its mechanism is still not totally understood, it is believed that N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) inhibits CO₂ or lactic acid receptors, but now we know that there are other odor receptors in the same neuron. The good part of the bad news is that researchers now understand that they need to focus their efforts on several receptors at once, not just one.

It remains to be seen whether this new discovery applies to other species of biting mosquitoes as well – Aedes albopictus, for example; other species of Anopheles, a genus of mosquitos that transmit malaria; or Culexus mosquitoes, such as the common mosquito or the tiger mosquito, which tend to inflict little more than discomfort or itching, except in rare cases. Christopher Potter, a neuroscientist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, fears that it does. In 2019, his lab found that fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) also had a double or triple expression of receptors in a single neuron, and in the spring of this year, they published findings indicating the same expression in a species of Anopheles mosquitoes.

Potter, who was not involved in the study, says that “this redundancy may be commonplace among insects.” Reflecting on the new findings, Potter explains how “the dogma prior to this was that an olfactory neuron would only express one type of olfactory receptor; that was the rule as far as we knew.” But, he says, “Dr. Vosshall’s work now suggests that a mosquito’s olfactory neurons may be much more adaptable, especially toward the key odors it needs to detect to locate its hosts.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.