Yes, mosquitoes really do like you better, and here’s why

Your body heat, the microbes on your skin, and even your clothes are determining factors when it comes to your attractiveness level for the tiny insects

Summer is here, and so are the mosquitoes. Nothing has the power to ruin a perfect evening like the buzzing sound that means its owner is in search of a warm meal of fresh blood. There are more than 3,000 species of this insect spread across the globe, enough to ruin our evening no matter where we happen to be.

These tiny creatures are considered the deadliest animals in the world, contributing to more than 725,000 deaths a year

It’s no joke, either. These tiny creatures are considered the deadliest animals in the world, contributing to more than 725,000 deaths a year. Not even humans cause this many fatalities: people kill around 475,000 other people a year. Snakes are behind some 50,000 human deaths, while dogs are responsible for 25,000 (mostly from rabies). Some of the world’s most feared animals, such as sharks or wolves, kill fewer than 10 people a year.

For those who wonder why mosquitoes make that buzzing sound, and for those desperate to know why they are always singled out by mosquitoes, even in a large group of people, here are a few facts to keep in mind.

Why do they buzz?

Mosquitoes do not buzz as a warning to their victims, but to alert other mosquitoes who are willing to breed. The sound is simply louder when the insects are flying around your head in search of a place to land.

Dr Louis M. Roth, who spent his younger years studying mosquito-borne yellow fever for the US Army, published a report in 1948 about the species Aedes aegypti, in which he found that males ignored females when these were resting quietly. But when the latter buzzed away, the males would go after them frantically upon hearing the distinct female flight sound.

Why do they always choose me?

Although both sexes make a buzzing sound, males do not bite: they feed on nectar. Now let’s see how the females select their victims.

The key lies in the chemical “landscape” in the air that surrounds us. Mosquitoes use specialized behavior and sensory organs to read the subtle chemical traces that our bodies emit. They depend on the CO2 that we exhale to find their hosts. When we breathe out, the CO2 does not immediately mix with the air, but creates temporary plumes that the mosquitoes follow. Like bloodhounds, they follow those tracks to locate targets as far as 50 meters away.

At this point, the mosquito has located the group of people in which you, the primary victim, are to be found. Things start getting personal at a distance of around one meter. At short range, these insects factor in several elements, such as your skin temperature, the presence of steam, and the color of your clothes.

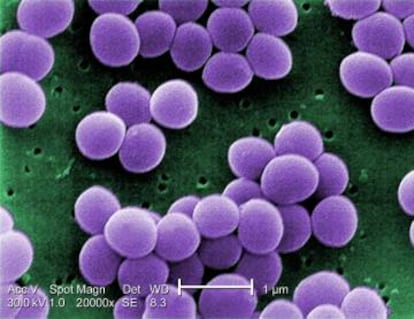

But scientists believe that the most relevant variable is the combination of chemical compounds produced by the colonies of microbes that reside in our skin. Bacteria turn the secretions from our sweat glands into volatile compounds that mosquitoes detect through olfactory sensors located in their antennae. There are over 300 different chemical compounds that are combined variously from person to person, depending on their genes and surrounding environment.

According to an article published in the science journal PLOS ONE, people with a greater diversity of microbes on their skin tend to get fewer bites than those with lower microbial diversity. These subtle differences can explain the great difference in the amount of times a person gets bitten by mosquitoes.

And since there is nothing we can do about this microbial mix on our skin, there is not much we can do to avoid the bites, except maybe avoid wearing black, which mosquitoes seem to love. This summer I’m wearing yellow.

Manuel Peinado Lorca is a professor at the Life Sciences department of the Franklin Institute of North American Studies at Alcalá University. A Spanish version of this article was originally published in The Conversation.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.