New study shows how metastasis progresses during sleep hours

Research with breast cancer patients evidences that cells capable of causing new tumors are more abundant and aggressive while the body is resting

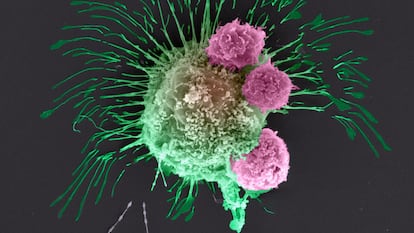

For years now, the dream of curing cancer has involved understanding and eliminating metastasis. This ability allows a tumor to send cells to the blood vessels, where they travel and nest in other organs and give rise to new tumors. Nine out of 10 cancer deaths are due to this process. A new study reveals that this expansion throughout the body is more aggressive at night, a surprising fact that may have important implications for the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Until now it was thought that tumors constantly emit cancer cells into the blood, regardless of the time of day. Swiss oncologist Nicola Aceto’s team took two blood samples from 30 women with breast cancer with and without metastasis; one at 10am and another one at 4am. The results show that the levels of so-called circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the blood are much higher at night and that these nocturnal cells are also much more aggressive.

Faced with the impossibility of marking and following the fate of each of the malignant cells detected in the patients, the researchers resorted to a set of experiments in mice. These animals are nocturnal, and the experiments showed that in these rodents, the tumor cells were much more active during the day, the mice’s rest period.

Tumor cells extracted during sleep are capable of causing metastasis if they are injected into healthy mice, something that does not happen with those obtained during the day. In both humans and mice, malignant cells activate genes that promote cell proliferation, a mechanism that fuels tumor growth. The work has been published in the prestigious journal Nature.

It is possible that sometimes we are bombing when the enemy is protected inside his bunkerAndrés Hidalgo, Spain's National Center for Cardiovascular Research

This study provides a new key to the relationship between cancer and the circadian rhythm, the internal clock that dictates the periods of physical and mental activity and rest during the 24 hours of the day. This cycle is intimately connected with the periods of day and night on Earth and its alteration due to unusual work schedules or artificial light is related to many diseases, including the risk of breast, prostate, colon, liver, pancreas or lung cancer. Jobs with night shifts that alter circadian rhythms are “probably carcinogenic,” the second most dangerous category out of four, according to the scale of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the United Nations.

The daily cycle is governed by hormones such as melatonin, which promotes sleep, and cortisol, which wakes us up. In 2014, a team from the Weizmann Institute in Israel demonstrated a connection between nocturnal hormones and the spread of cancer. In mice, they showed that administering the same oncological drug reduced tumors more or less depending on whether it was administered during the day or at night. The new work also sees a clear connection between hormones and metastasis, so that molecules of this type that start the daily activity phase seem to reduce the cancer’s ability to travel through the circulatory system.

Harrison Ball and Sunitha Nagrath, from the Rogel Cancer Center at the University of Michigan (USA), point out that these results have “surprising implications” in cancer treatment. Both researchers call for large-scale clinical trials with patients to confirm these results. “Oncologists may need to be more aware of what time of day they administer some treatments,” they add.

Roger Gomis leads the metastasis research group at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Institute. “This work is important from a conceptual point of view,” he highlights. “It is in line with other works that are revealing a systemic component in cancer and its expansion. An example would be the effects of diet on the success of some cancer treatments”, he details. “The difficult thing,” he warns, “will be applying this basic knowledge to treatment and diagnosis, because it is impossible to prevent patients from sleeping, while taking biopsies in the wee hours of the morning poses great challenges,” he argues.

María Casanova, a researcher at Spain’s National Cancer Research Center, believes that the work has “enormous” value. “It is necessary to extract a lot of blood to measure the circulating tumor cells, and in very advanced stages it is something very delicate. It is only done in a few patients to see how well chemotherapy is working for them. Having these data from 30 patients is really a lot,” she notes.

The fact that metastatic cells are more active at night is not accidental. Humans are a diurnal species and during the day we are more exposed to harmful viruses and bacteria than at night. This is why the part of the immune system that patrols the circulatory system is less active at night, when we rest. This partly explains why fever or asthma attacks tend to be more intense at night. During the hours of rest, other immune cells are activated, the neutrophils, which are fixed in the different organs and help to repair them. Cancer has its own circadian clock and it would be precisely at this time when the cancerous cells of the tumor leave the tissues and jump into the bloodstream, where there is hardly any surveillance, explains Casanova.

There are cancer treatments that are less effective if they are administered in the afternoon. There are also components of the circadian rhythm that could explain other ailments, such as the fact that most strokes happen in the morning, Casanova says. The specific mechanisms that explain these observations are still unknown, but there is already an emerging discipline called chronotherapy that studies the confluence of the disease, the therapies applied and the time of day and night. “It is possible that we can find a way to synchronize the immune system so that it is better able to fight cancer when it is more active,” summarizes Casanova.

Andrés Hidalgo, a researcher at Spain’s National Center for Cardiovascular Research, points out that this study is “shocking.” “It presents us with a less predictable biology of cancer than we thought and obviously confirms that the disease does not follow the same schedules as our medical staff. This can be very important because it has been seen that radiation is much more effective if it is applied when the tumor is in the active phase and multiplying, and not in the resting phase. It is possible that sometimes we are bombing when the enemy is protected inside his bunker.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.