Sagittarius A*: The inside story of how the Milky Way’s black hole was snapped

Spanish investigator José Luis Gómez, who took part in capturing the first image of the cosmic giant in our galaxy, recounts how the milestone was achieved and what it means for future research

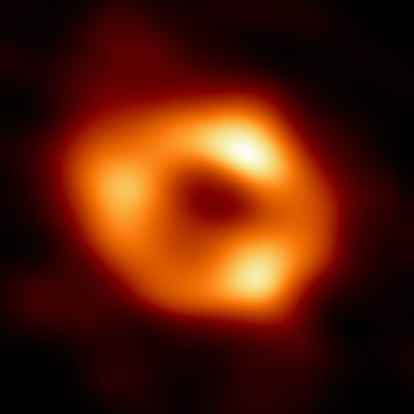

On April 10, 2019, researchers at the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed to the world the first image of a black hole, that of the M87 galaxy. On Thursday, the same team shared a photo of the black hole that resides in the center of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. This is “our” black hole, a cosmic giant that contains four million suns and is located about 26,000 light-years away from us, in the constellation of Sagittarius, for which it gets its nickname Sagittarius A*, or SgrA * as it is known among friends. And SgrA* has been a friend to EHT researchers for many years. But taking a photo of it has been much more difficult than with M87. The reason why? It does not stay still!

In the photo of a black hole, we see the incandescent gas that revolves around the event horizon, the point of no return out of the universe. This gas moves around the black hole at close to the speed of light, the maximum possible, but while it takes weeks to orbit M87, with SgrA*, which is about 1,000 times smaller, it takes only minutes. This means the photo changes as the EHT watches for an entire night. It’s like trying to take a photo at night of a child who won’t stop moving.

EHT researchers have spent years developing new algorithms that have allowed us to account for the rapid movement of gas around SgrA*. We have made literally tens of millions of images with simulated data to refine our programs and models, a process akin to searching for the lens and filter to give us that perfect snapshot. Once everything was ready, we took thousands of images of SgrA*. Each of these images is slightly different, but the vast majority show the characteristic ring of light around a black hole with slight variations in the distribution of brightness. The image shown to the world is an average of these images, revealing the giant at the center of our galaxy.

Black holes are one of the strangest and most enigmatic objects that we can find in the universe, but at the same time, they are also one of the simplest. According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, the size of a black hole is indicated only by its mass and, to a much lesser extent, how fast it rotates (its spin). Previous studies, worthy of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2020, allowed us to understand the mass of SgrA* in great detail, so we knew very well (with much greater precision than for M87*) how big SgrA* should have been. The ring of light in the EHT image is exactly 52 microarcseconds in size (about the size of a donut on the Moon), in perfect agreement with relativity theory.

SgrA* is about 1,000 times smaller than M87, and yet the two black holes are exactly the same, only their size is different. For the first time, we confirm this fundamental property of relativity. Einstein is still right!

There are no memories sweeter than those of childhood and, for me, who as a child spent summer nights on the farm looking at the stars and dreaming of deciphering the enigmas of the universe, there can be no greater reward than being part of the team that obtained the first images of black holes. Sometimes reality surpasses your wildest dreams!

But this is only the beginning. In the coming years, we will continue to expand and improve the network of antennas that make up the EHT, presenting increasingly sharper images with which to perform increasingly precise tests of general relativity. And of course, we want to make movies of black holes! (Watch out Hollywood...) In the next few years, we will see how the black hole in M87 engulfs part of the gas around it, and we will learn how energy is extracted from black holes to form the jets that emanate in their vicinity and extend beyond the galaxy itself. And what better way to carry out this journey of scientific discovery than in the company of my colleagues and friends at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia in southern Spain – Antonio Fuentes, Guang-Yao Zhao, Rocco Lico, Thalia Traianou, Ilje Cho and Antxon Alberdi. They are models of professionalism and dedication, without whom it would not have been possible to obtain the image of the black hole in the center of our galaxy.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.