The AI device that can detect counterfeit handbags

With the sale of knock-offs on the rise, brands and buyers are using tech to differentiate between a real bag and a fake one

“I’m going to show you a fake bag so you can see how spectacular an imitation can be.” Lucía De La Calle, is an appraiser at the second-hand luxury handbags boutique Del Páramo Vintage in Valladolid, in northwest Spain. She shows EL PAÍS a Louis Vuitton Twist MM bag, a classic model that the brand wants to make a basic, betting on its reissue year after year in different colors.

Its cost is €3,500. “I think my eye is quite trained but, often, even I am unable to perceive the difference,” says De La Calle.

The woman who bought this bag for €2,500 on the second-hand market brought it to the store with the brand’s characteristic orange box and authentic dust cover, as well as a copy of the invoice from its previous owner.

De La Calle is tasked with doing a preliminary appraisal that she calls a “sandwich analysis:” examining the exterior, interior, then exterior again. In this case, the analysis was simpler than usual because there happened to be an original model in store.

“First things first: I put the bag on the table and pick up the chain, because there are chains and then there are chains. The texture, the solidity, the cold, the shine... everything tells you something,” she explains. “The second thing is the weight: a good bag is not usually light. Nowadays, the brand’s website has the exact weight of each bag – but just like we consult these numbers, so do the counterfeiters. Then you have to look at the details: see if the seams are straight or if there are double threads. Luxury items are always perfect – those with flaws are discarded before they go on the market. This bag was impeccable.”

De La Calle then brings her attention to the interior. Counterfeiters tend to take more care of the external appearance of the bag and often neglect the interior: linings, stamps, labels or finishes can reveal the difference between an authentic bag and a fake.

“We open it and the first thing we look at is the stamp,” says the evaluator. The stamp “comes with a silver bas-relief that is exactly the same as that of an original bag – it comes with the little mirror bearing the brand’s signature.” The stamp appears totally authentic, “but then I see the first detail that makes me suspicious.”

Since 1980, Louis Vuitton has included a label with a code. The code has two letters and four numbers that indicate the place and date of manufacture. This is a guarantee for customers, who can consult the code to make sure that their bag was indeed made in France in 2006.

“This bag included the code, a good sign,” continues De La Calle, “but instead of being placed in such a way that, when I opened the bag, I could read it, I had to turn the bag around to do so. It’s silly, but counterfeiters neglect these kinds of details.”

To top off the analysis, De La Calle notices that the stamp on the inside of the bag is very close to the seam, while it is a few centimeters lower on the other bag they had in the store. De La Calle determines that the woman’s bag was a fake.

“When you tell a customer that their bag is fake, first they say ‘that’s impossible,’ and then they get angry,” explains Sheila Guerrero, the co-founder of the Del Páramo Vintage store. “And I get it, most people who come to our store have paid a minimum of €500 for a bag, usually, a hell of a lot more.” Guerrero says that every week at least one bag in the store turns out to be fake: “The most faked bags are usually Chanel and Louis Vuitton – people pull towards classic and timeless bags.”

The fake Louis Vuitton Twist was one such case: the woman who brought it in didn’t believe it could be a fake, she even had the receipt. “The problem with the scam is that it is becoming more and more professional: now they sell you bags that include an invoice, because there are companies that forge even the invoice of the stores,” explains Guerrero. After all, if someone can forge a bag, how can they not forge a piece of paper. In other situations, “there are those who buy an original bag and then 25 fakes, and they send you the photographs and the invoice of the original... but then they send you the fake,” explains Guerrero. For these cases, Del Páramo Vintage has a device that, by means of Artificial Intelligence (AI), can detect a fake in record time.

AI against fakes

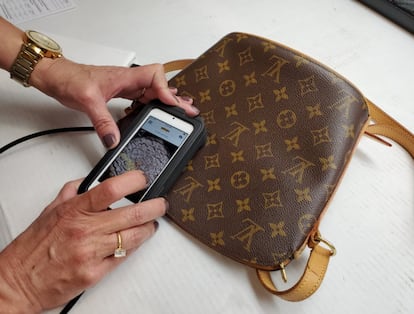

Lucia De La Calle brings out an iPod with a built-in device that has a huge lens. The valuator then opens an app called Entrupy and the system begins to guide her through the authentication process: select the brand; the model if you know it; choose the type of leather. Then, the app asks for a series of photographs: exterior (bag from the front, bag from the side, exterior label logo, zipper closure), interior (pockets, labels, ‘Made in’ statement) and, finally, microscopic, where the aforementioned lens magnifies an object up to 260 times and is able to identify the most subtle differences between colors or fabrics.

In less than 30 seconds in the most obvious cases, this little gadget identifies everything that can take a person hours to do, and it will convince even the customer in the worst stage of denial.

Vidyuth Srinivasan is the co-founder and CEO of Entrupy. Launched in 2016, the company behind the app aims to end counterfeit luxury handbags and sneakers and already operates in more than 65 countries.

“The way the system works is that from our app we ask our users to choose the model of the bag in front of them and take a series of pictures,” Srinivasan explains from New York. “Then, they upload those images to our cloud. What’s in that cloud is a set of algorithms for each brand that allows you to authenticate any model that has that brand,” he says.

“We have over 2,000 metrics that we use on each image to analyze and help the algorithm make the decision. So this set of algorithms at the end makes a report where they say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ Or in other words, ‘authentic’ or ‘fake’.” The algorithm has been trained through thousands and thousands of product images. Over time, the more users use the service, the more images they get to include. This translates into more data, and with more data the algorithm is updated and improved.”

And then there’s the microscope lens. “When we started, we didn’t want to have an external device, because as a business you think ‘how many people are going to want a device?,’ but then we realized that, with the quality that fakes have now and the level at which good fakes are made, we couldn’t just settle on being able to spot the easy fakes, we had to get to spotting the hard ones,” Srinivasan says. “To solve this problem we had to be able to create images at a level where you could see huge differences, maybe not to just anyone, but to the trained eye of our algorithm.”

Entrupy is part of La Maison des Startups, the LVMH group’s startup accelerator, to which brands such as Louis Vuitton, Fendi or Christian Dior, among others, belong.

The CEO explains that the companies that use Entrupy and the customers passing their handbag through the AI filter can expect secure results due to, firstly, its high reliability: “We have above-99% accuracy in correctly differentiating authentic products from fake products,” says Srinivasan.

To counter any gap between 99 and 100%, the algorithm is programmed to give more false negatives (authentic bags that the app marks as “unidentified”) than false positives: “False positives would be when we have a fake, but we take it for granted, this is the worst-case scenario for anyone... except for the guy who is trying to sell you a fake bag, of course,” says Srinivasan. In “unidentified” cases, the human technical team is brought in to determine the authenticity or otherwise of the product.

Entrupy also provides a guarantee. “Our goal is that there are no counterfeits in the market and people have more security when buying products,” says Srinivasan. It is for this reason that Entrupy offers a certificate of authentication, a kind of diploma that can already be seen on the pages of guides to second-hand goods for sale (“Chanel bag authenticated by Entrupy”). “As part of this certificate we give what we call a financial guarantee,” says the CEO, meaning “we are so sure of the reliability of our own technology that, if we make a mistake, we will pay the money a customer has paid for a counterfeit.”

A market full of counterfeits

“As of today, our workload is more in appraisal and verification than in product purchase,” explains the co-founder of Al Paramo Vintage, who notes that since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, the number of fakes among original handbags has not stopped increasing. Vidyuth Srinivasan agrees: “Yes there has been an increase in counterfeits in the wake of the pandemic, I don’t know what the official reason behind it is, but I would venture to say it’s because, globally, there are more people looking for liquidity so there are more people getting rid of things and more transactions happening in general. Further, there has been an increase in online trading where it is easier to sneak counterfeits.”

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), sneakers along with fashion and luxury goods are among the top three most counterfeited products. According to 2019 data, the volume of international trade in counterfeit and pirated products was estimated at $464 billion, or 2.5% of global trade. Apps and pages which sell second-hand products between individuals and social networks, such as Instagram, are the places where the supply and demand for these items has increased the most, and where a buyer has the fewest guarantees and security. While classic and timeless luxury brands, as Sheila Guerrero rightly points out, are among the most counterfeited, criminals are also increasingly focusing on limited releases, latest models or smaller brands.

“Often luxury brands follow a strategy of limiting certain products,” Guerrero explains. “This often leads to a rise in the second-hand market. In the end, secondhand prices are as standardized as in retail, both in jewelry and handbags, and there are usually no bargains. My only advice for those who want to buy a second-hand product would be the following: be wary if someone offers you a Chanel for 500 euros – most likely it is a fake.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.