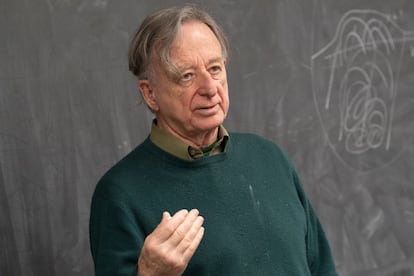

Dennis Sullivan, the man who sees abstract worlds in his mind, wins the ‘Nobel’ of mathematics

The mathematician has been awarded the Abel Prize ‘for his groundbreaking contributions to topology’

One day in 1966, there was an intellectual shipwreck in the North Sea. The American mathematician Dennis Sullivan was traveling on the deck of a boat headed to Scandinavia and was using the time – and a pen and paper – to solve a fiendish problem in an unimaginable, abstract world of eight dimensions. He was 25 years old and had an exceptional brain, but he ended up with an unexpected result. He suddenly threw the notebook over the side, but then carried on thinking and persevered. On Wednesday of this week, Sullivan – who was born in Port Huron 81 years ago, won the Abel Prize, which is considered the Nobel of mathematics and includes a €775,000 ($851,000) cash award.

That young researcher focused on topology, the study and classification of shapes. One classic example is that of a balloon in the form of a donut, which can be squashed to create a multitude of variations but can never be spherical. Its invariant property is that it has a hole. That is why mathematicians often joke that, for a topologist, a coffee mug and a donut are the same thing. Sullivan, from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, is one of the best topologists of the last century. He has shone in the classification of highly complex structures, in spaces with a multitude of dimensions.

The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, which awards the Abel Prize, stated in a press release that Sullivan has “repeatedly changed the landscape of topology by introducing new concepts, proving landmark theorems, answering old conjectures and formulating new problems that have driven the field forwards, adding that he “has moved from area to area, seemingly effortlessly, using algebraic, analytic and geometric ideas like a true virtuoso.”

Sullivan renewed topology when he was still in his twenties, and condensed his ideas into a document in June 1970, when he was a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He never published those papers, but his colleagues began to photocopy them and they circulated all over the world, via copies that were increasingly difficult to read, but that still maintained their own aura of a sacred text.

They became known as “The 1970 MIT notes,” and were finally published in 2005. The British mathematician Andrew Ranicki commented at the time that those photocopies were translated into Russian and published in the Soviet Union in 1975, like a kind of samizdat, clandestine editions of works that were banned by the Communist dictatorship. “As noted in Mathematical Reviews, the translation does not include the jokes and other irrelevant material that enlivened the English edition,” complained Ranicki in the editor’s preface of the publication in 2005.

“New concepts”

The Norwegian Academy has applauded the fact that the US mathematician has “repeatedly changed the landscape of topology by introducing new concepts.” It continued: “Developing a precise language and quantitative tools for measuring the properties of objects that do not change when they are deformed has been invaluable throughout mathematics and beyond, with significant applications in fields ranging from physics to economics to data science.”

In recent years, Sullivan has come up against major mathematical challenges in a bid to save human lives. In 2014, after winning more than €700,000 ($770,00) with the Balzan Prize – awarded “to scholars and scientists who are distinguished on an international level” – he announced that he would be setting a team of young researchers the task of perfecting complex theoretical algorithms with the aim of predicting phenomena such as the behavior of hurricanes and the dispersion of pollutants due to the wind. “It is fascinating and challenging that these problems are up to the present day mathematically intractable,” he said at the time. Half a century after having thrown his ideas overboard, the mathematician is clearly still on form.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.