The underwater ‘hotspot’ feeding La Palma’s volcano will create new islands

The magma flow that shaped Spain’s Canaries archipelago 20 million years ago continues to add landmass, while Fuerteventura and Lanzarote are destined to sink under the effects of erosion

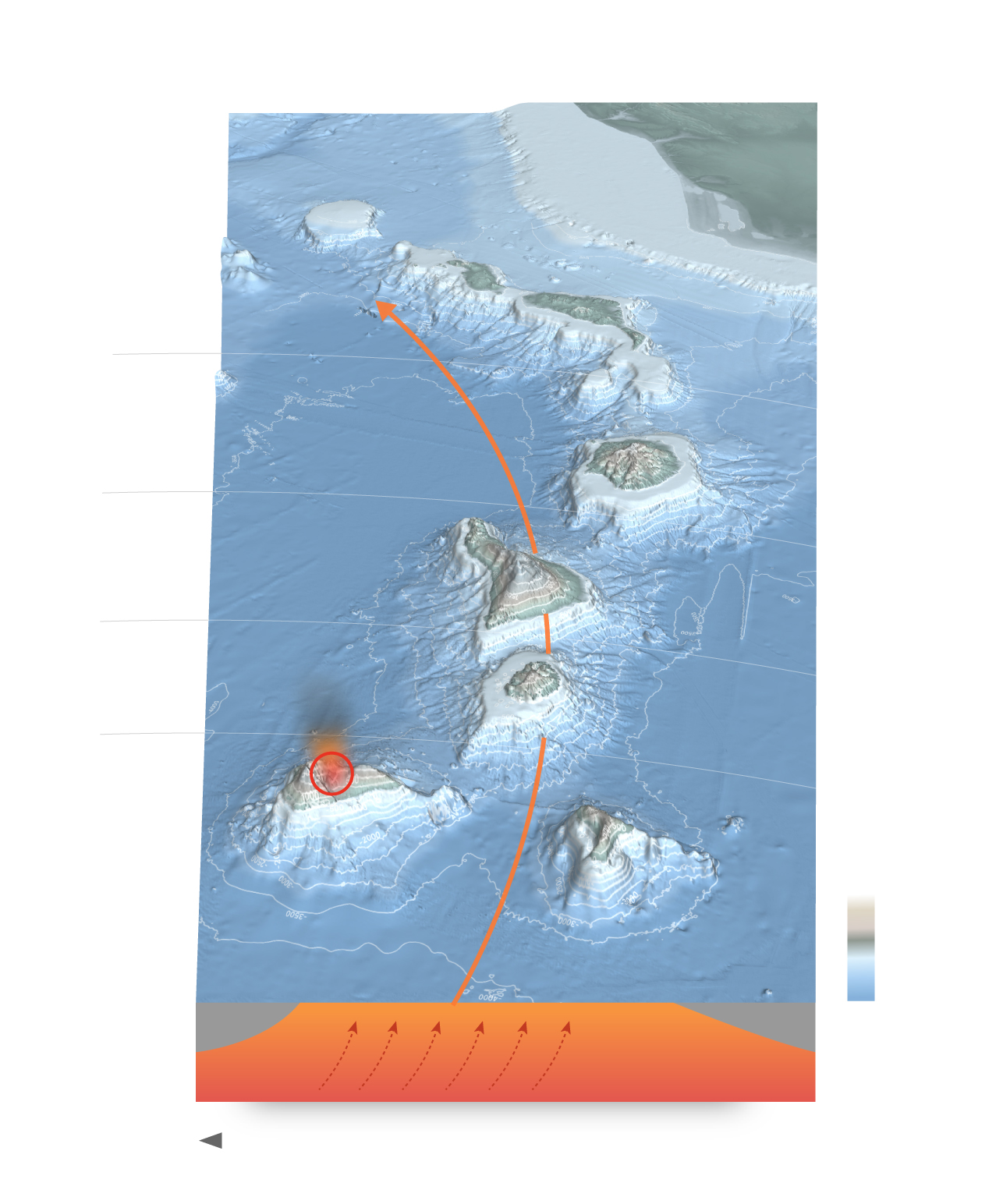

Lithosphere

Lava

flow

Asthenosphere

Mantle

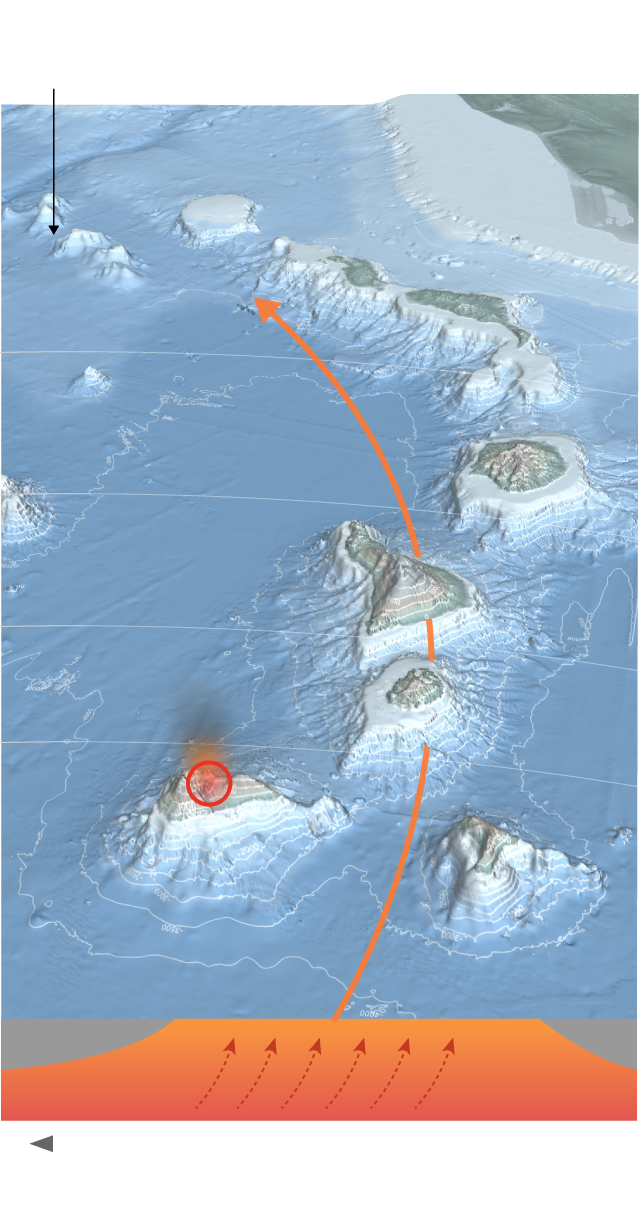

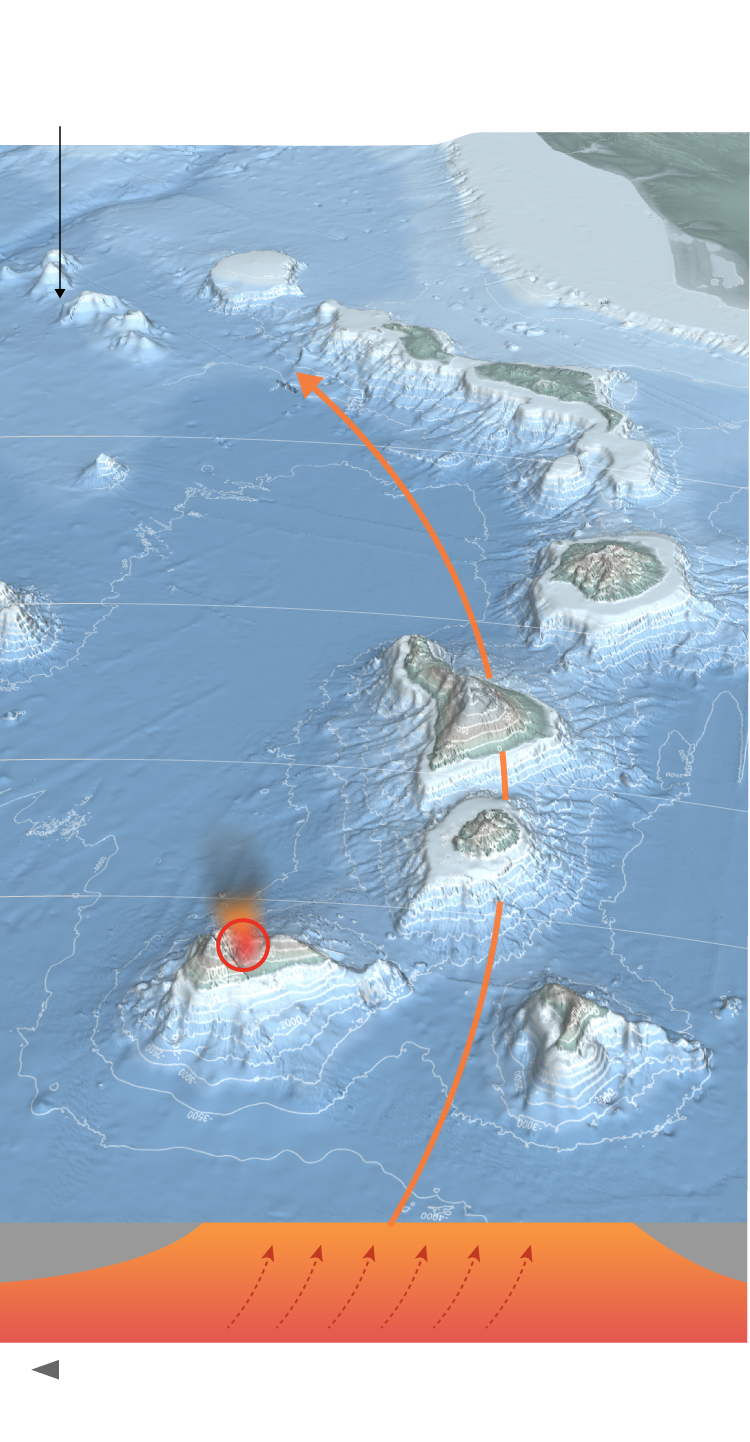

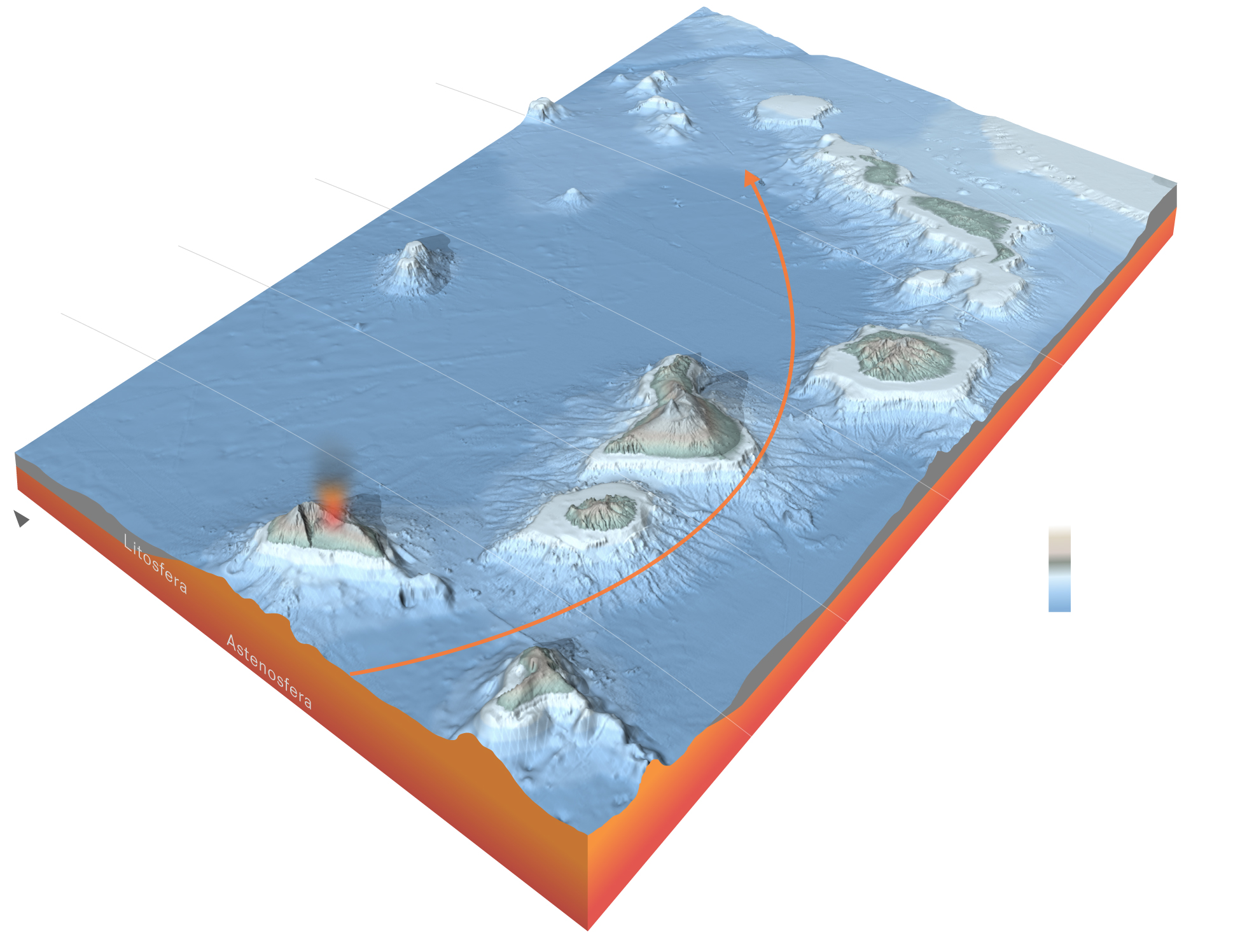

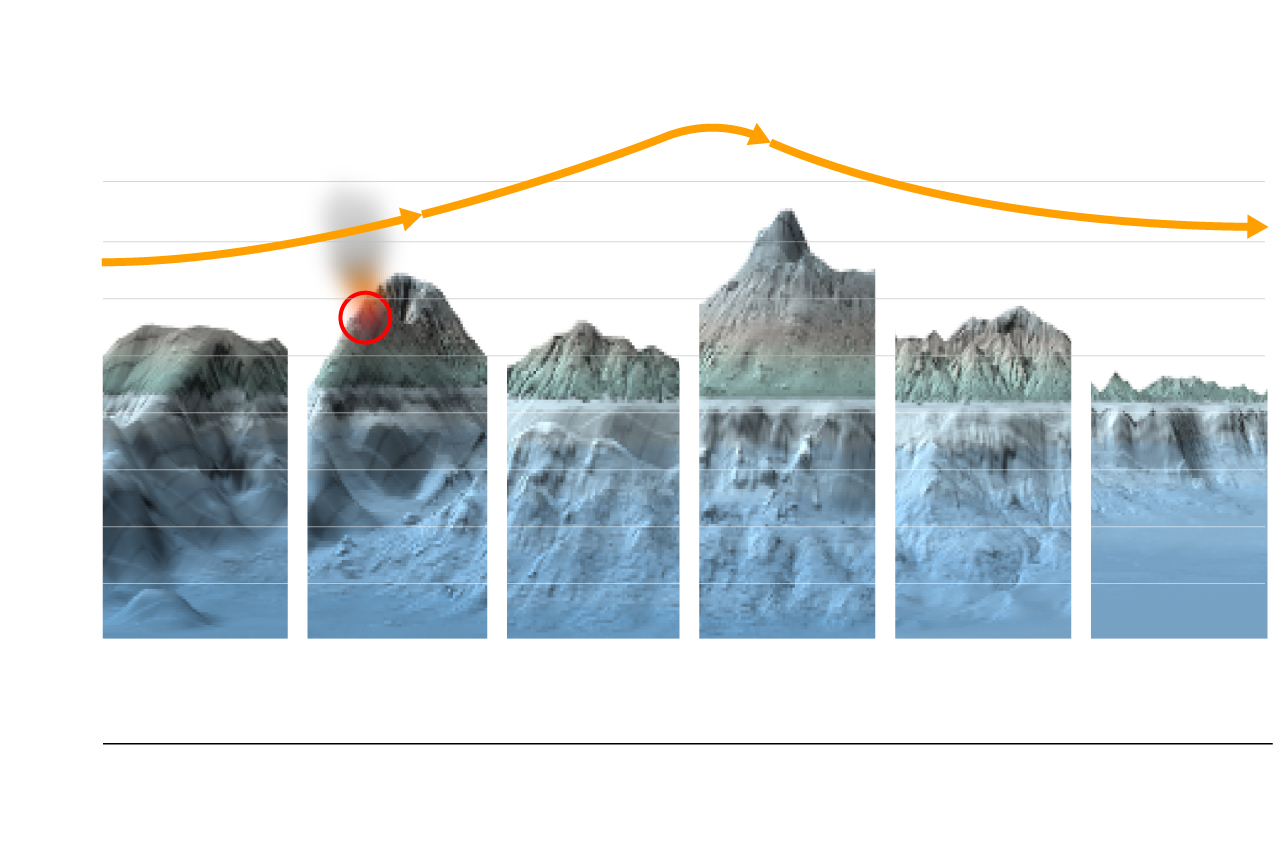

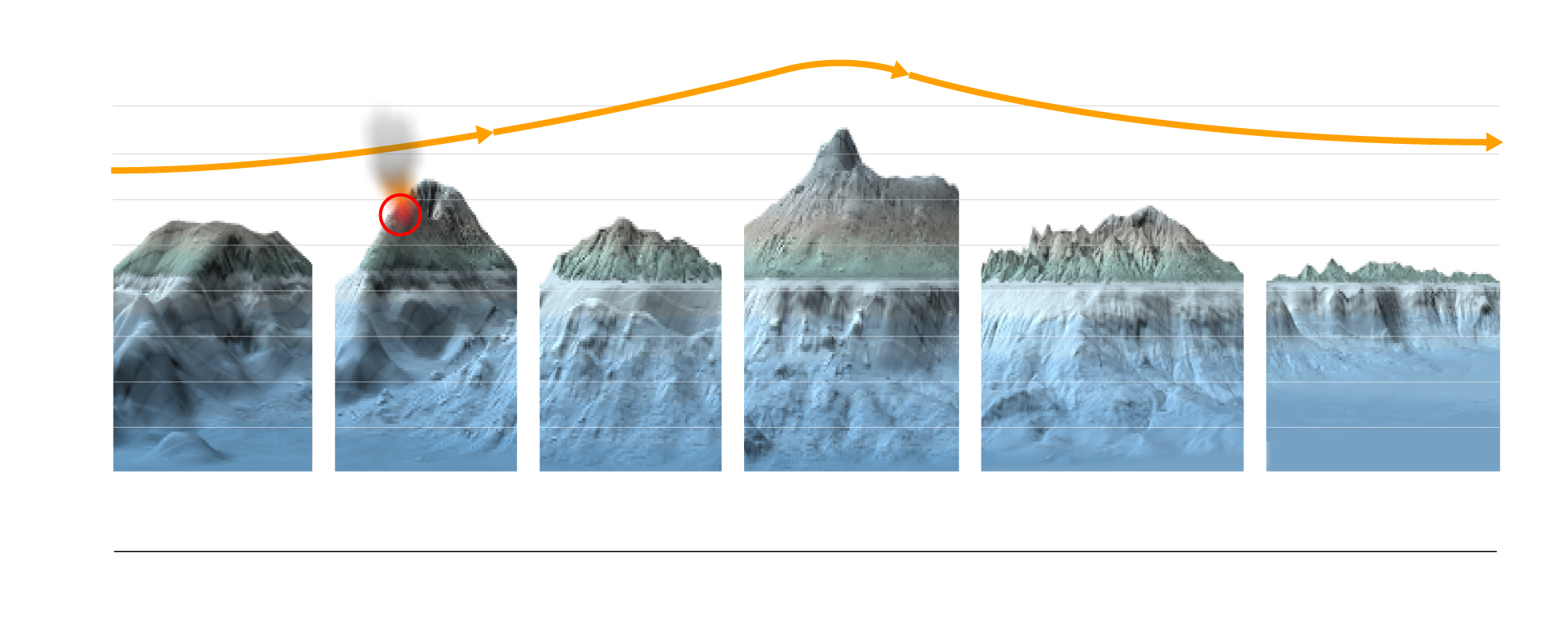

Simplified outline of the geological evolution

of the Canary Islands over 20 million years.

Atlantic Ocean

Younger islands

Older islands

Lithosphere

Lava

flow

Asthenosphere

Mantle

Simplified outline of the geological evolution of the Canary Islands over 20 million years.

The Canary Islands lie on the African Plate, which “floats” over the Earth’s mantle in an easterly direction, moving at a speed comparable to the growth of fingernails. About 20 million years ago, the plate started to move over the “hotspot” that injected magma and began to create the first islands – now the oldest islands – of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. La Palma and El Hierro are the youngest islands, at just 1.8 million and 1.2 million years old respectively. The hotspot is still beneath them and that is why they have active volcanoes that make them grow and extend in surface area.

Formation of the islands

Millions of years

ÁFRICA

-1,500

-500

Lanzarote

20.2

Fuerteventura

-3,000

Progression

by age of the

islands

14.5

Gran Canaria

El Teide 3,715 m

11.9

Tenerife

9.5

La Gomera

El Hierro

1.8

La Palma

Atlantic

Ocean

-3,500

-4,000

Litosphere

Asthenosphere

Mantle

North

Formation of the islands

Millions of years

ÁFRICA

-1,500

-500

Lanzarote

20.2

Fuerteventura

-3,000

Progression

by age of the

islands

14.5

Gran Canaria

El Teide 3,715 m

11.9

Tenerife

9.5

La Gomera

El Hierro

1.8

La Palma

Atlantic

Ocean

-3,500

-4,000

Litosphere

Asthenosphere

Mantle

North

Formation of the islands

Millions of years

ÁFRICA

-1,500

-500

Lanzarote

20.2

Fuerteventura

-3,000

Progression

by age of the

islands

14.5

Gran Canaria

El Teide 3,715 m

11.9

Tenerife

9.5

La Gomera

El Hierro

1.8

La Palma

Altitude

3,500

Atlantic

Ocean

0

-3,500

-4,000

-4,000

Litosphere

Asthenosphere

Mantle

North

20.2

Formation of the islands

Millions of years

-1,000

14.5

-500

Lanzarote

ÁFRICA

Fuerteventura

11.9

Progression

by age of the

islands

9.5

Gran Canaria

Tenerife

Atlantic Ocean

1.8

-3,500

El Teide 3,715 m

La Gomera

-3,000

La Palma

Altitude

3,500

North

0

-4,000

-3,500

-3,000

El Hierro

Mantle

This maps shows the submarine relief of all the Canary Islands and their surroundings, complete with other now extinct volcanoes that emerged as islands millions of years ago, such as those seen to the north of Lanzarote.

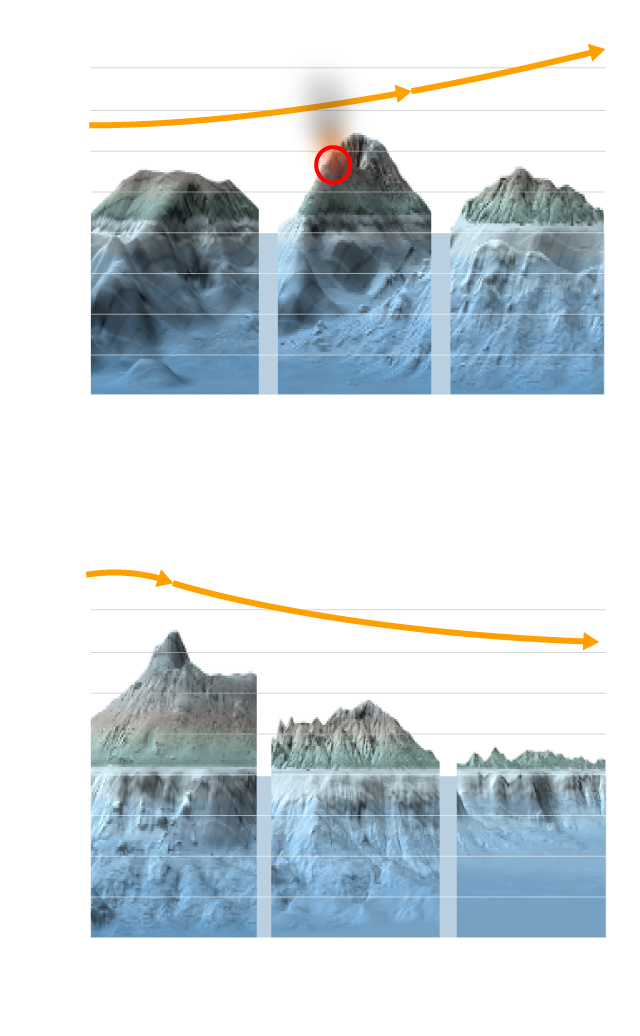

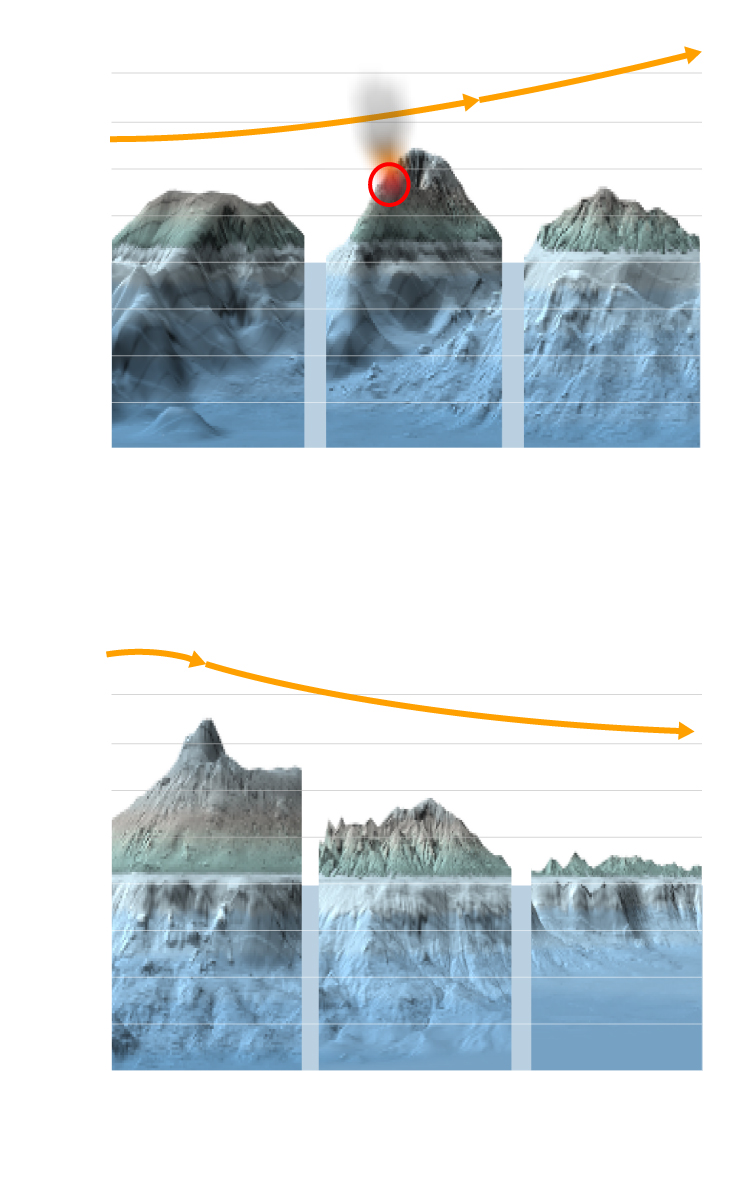

Altitude

4,000

Birth

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

El Hierro

La Palma

La Gomera

Maximum

growth

Dismantling

4,000

Teide 3,715 m

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

Tenerife

Gran Canaria

Fuerteventura

y Lanzarote

Altitude

4,000

Birth

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

El Hierro

La Palma

La Gomera

Maximum

growth

Dismantling

4,000

Teide 3,715 m

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

Tenerife

Gran Canaria

Fuerteventura

and Lanzarote

Maximum

growth

Altitude

Dismantling

4,000

Birth

Teide 3,715 m

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

El Hierro

La Palma

La Gomera

Tenerife

Gran Canaria

Fuerteventura

and Lanzarote

Less than 2

9.4

14.5

20

million years

Maximum growth

Dismantling

Altitude

4,000

Birth

Teide 3,715 m

2,000

0

-2,000

-4,000

Fuerteventura

and Lanzarote

El Hierro

La Palma

La Gomera

Tenerife

Gran Canaria

Less than 2

9.4

14.5

20

million years

Volcanologists believe that the magma flow is currently under La Palma. In 2011, it created a submarine volcano close to the island of El Hierro that almost reached the surface. This is how all the islands, which are actually huge volcanoes, originated. From the bottom of the sea, La Palma is about 6,500 meters high – almost as tall as the highest peak of the Andes. Similarly, the oldest islands, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, are disappearing through erosion and will eventually be submerged.

“The volcanic eruption of La Palma is undoubtedly the most destructive one in Spain’s history,” says Juan Carlos Carracedo, a 79-year-old geologist from the northern region of La Rioja who has spent most of his life studying volcanic activity in the Canary Islands, which are located off the northwestern coast of Africa. Since the Castilians conquered La Palma in 1493, there have been seven other recorded volcanic eruptions whose lava swept away houses, crops and even ports. But their impact was not as significant as the island was far less populated then and had not yet established economic engines of growth such as tourism or banana greenhouses. “Not even the Timanfaya on the island of Lanzarote in 1730 caused this much damage,” says Carracedo, a professor emeritus at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Lava tongue

Todoque

Todoque

Mountain

Altitude

110 m

90 m

Updated: October 1

0 m

-19 m

-60 m

Lava tongue

Todoque

Todoque

Mountain

Altitude

110 m

90 m

0 m

Lava advance updated with Copernicus data from October 1

-19 m

-60 m

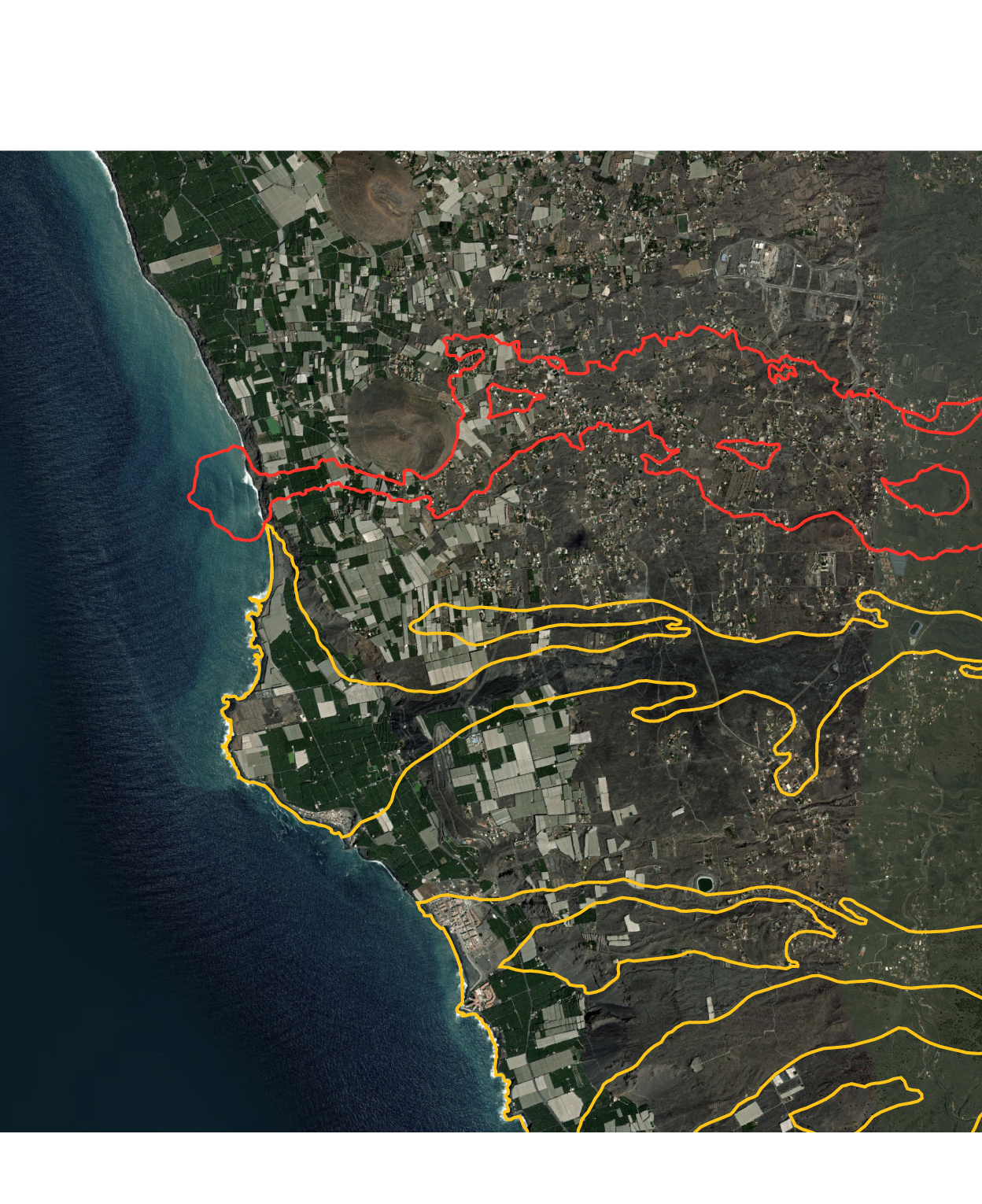

The graphic above shows the eruption of the Cabeza de Vaca volcano on La Palma from September 21 to October 1. The rivers of lava have destroyed or damaged more than a thousand buildings, far more than recorded in other eruptions. It is the latest chapter in a history of volcanic activity that began more than 20 million years ago. It is both a destructive and creative phenomenon, for without volcanoes none of the Canary Islands would exist.

In the last five centuries, all La Palma’s volcanoes have emerged in Cumbre Vieja, a spectacular mountain range featuring almost 30 craters that extends to the south of the island. This is probably the only place in Spain where in just a few hours you can touch stones that originated in the last five centuries; it is the country’s youngest terrain.

As is the case now, the lava tongues of most of the previous eruptions advanced along the western slopes of Cumbre Vieja. Many of them reached the sea and created platforms that enlarged the surface of the island.

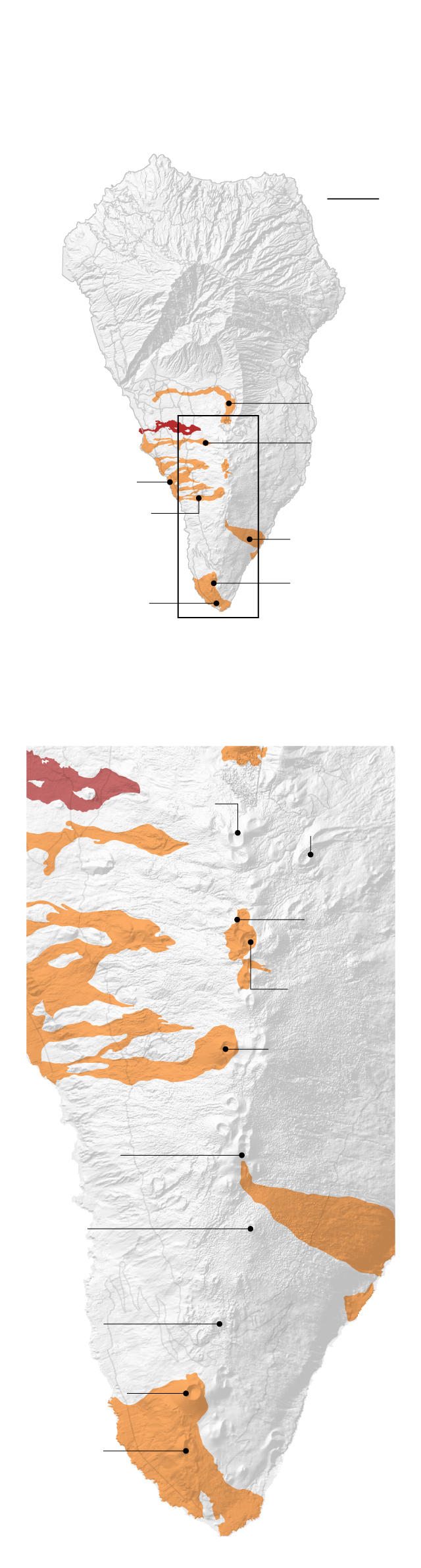

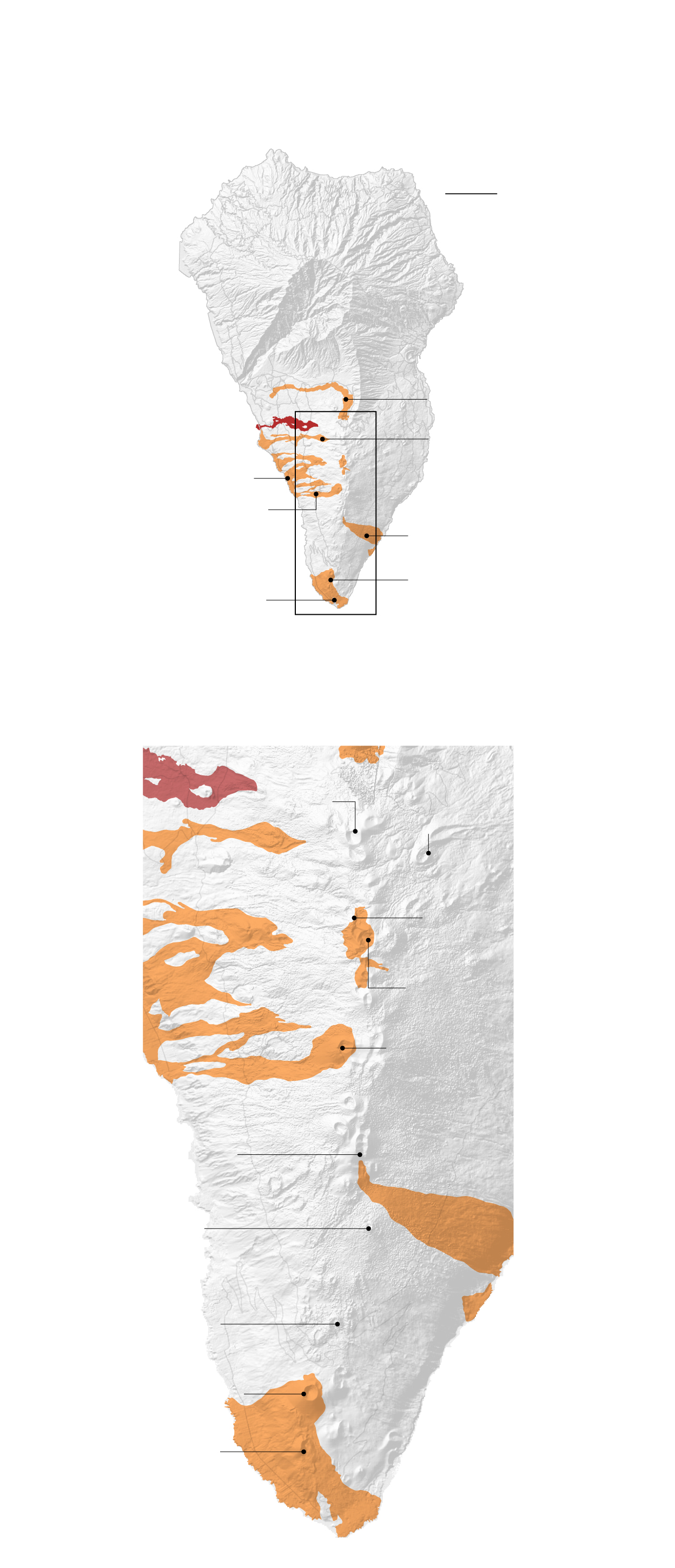

More active in the south

The volcanic mountain range extending south of La Palma is the youngest and most active area. The most-recent eruptions have occurred in this area.

5 km

La Palma

Caldera de Taburiente

1430

Tacande

2021

Cumbre Vieja

1949

San Juan

1585 Tahuya

Cumbre

Vieja

1712 El Charco

1646 Martín

1667

San Antonio

1971 Teneguía

The Cumbre Vieja Natural Park is a series of craters and active volcanoes.

San Juan

volcano

Caldero

mountain

Tahuya

volcano

Nambroque

mountain

Los Lajones

mountain

Cumbre Vieja

San Martín

volcano

Fuego

mountain

El Rivero

San Antonio

volcano

Teneguía

volcano

More active in the south

The volcanic mountain range extending south of La Palma is the youngest and most active area. The most-recent eruptions have occurred in this area.

5 km

La Palma

Caldera de Taburiente

1430

Tacande

2021

Cumbre Vieja

1949

San Juan

1585 Tahuya

Cumbre

Vieja

1712 El Charco

1646 Martín

1667

San Antonio

1971 Teneguía

The Cumbre Vieja Natural Park is a series of craters and active volcanoes.

San Juan

volcano

Caldero

mountain

Tahuya

volcano

Nambroque

mountain

Los Lajones

mountain

Cumbre Vieja

San Martín

volcano

Fuego

mountain

El Rivero

San Antonio

volcano

Teneguía

volcano

More active in the south

The volcanic mountain range extending south of La Palma is the youngest and most active area. The most-recent eruptions have occurred in this area.

5 km

La Palma

Caldera de Taburiente

1430

Tacande

2021

Cumbre Vieja

1949

San Juan

1585 Tahuya

Cumbre

Vieja

1712 El Charco

1646 Martín

1667

San Antonio

1971 Teneguía

The Cumbre Vieja Natural Park is a series of craters and active volcanoes.

San Juan

volcano

Caldero

mountain

Tahuya

volcano

Nambroque

mountain

Los Lajones

mountain

Cumbre Vieja

San Martín

volcano

Fuego

mountain

El Rivero

San Antonio

volcano

Teneguía

volcano

More active in the south

The volcanic mountain range extending south of La Palma is the youngest and most active area. The most-recent eruptions have occurred in this area.

The Cumbre Vieja Natural Park is a series of craters and active volcanoes.

5 km

La Palma

San Juan

volcano

Caldera de Taburiente

National Park

Caldero

mountain

Tahuya

volcano

1430

Tacande

2021

Cumbre Vieja

Nambroque

mountain

1949

San Juan

1585 Tahuya

Cumbre

Vieja

Los Lajones

mountain

1712 El Charco

1646 Martín

Cumbre Vieja

1667

San Antonio

San Martín

volcano

1971 Teneguía

Fuego

mountain

El Rivero

San Antonio

volcano

Teneguía

volcano

“The eruption that gained the most new land from the sea was the one in 1949,” explains Carracedo. “The area was covered with fertile soil brought from another part of the island and they planted banana trees – a tropical plant that grows best at sea level, meaning they are now among the most bountiful on the island.”

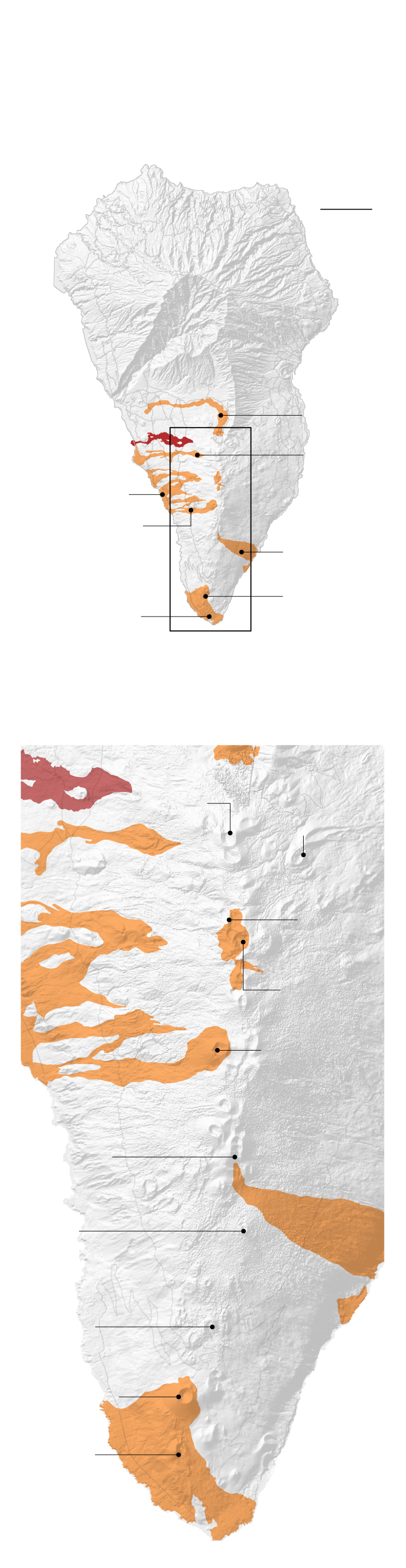

Land reclaimed from the sea

The current eruption and those during the last 500 years have caused the island to extend westward, leaving lava platforms on the seabed.

Todoque

2021

Cumbre Vieja

1949

San Juan

Puerto Naos

Algunas de las plantaciones de plátano canario más productivas de toda la isla se asientan hoy sobre la Land reclaimed from the sea por la erupción del volcán San Juan en 1949.

1585

Tahuya

Actualizado con datos de la erupción

del 1 de octubre de 2021 (Copernicus).

Land reclaimed from the sea

The current eruption and those during the last 500 years have caused the island to extend westward, leaving lava platforms on the seabed.

Todoque

2021

Cumbre Vieja

1949

San Juan

Puerto Naos

Algunas de las plantaciones de plátano canario más productivas de toda la isla se asientan hoy sobre la Land reclaimed from the sea por la erupción del volcán San Juan en 1949.

1585

Tahuya

Actualizado con datos de la erupción

del 1 de octubre de 2021 (Copernicus).

Land reclaimed from the sea

The current eruption and those during the last 500 years have caused the island to extend westward, leaving lava platforms on the seabed.

Todoque

2021

Cumbre Vieja.

So far, the eruption

has created more

than 30 hectares

of land on the sea.

1949

San Juan

Puerto Naos

Some of the most-productive banana plantations on the island are located on land reclaimed from the sea by the eruption of the San Juan volcano in 1949.

1585

Tahuya

Actualizado con datos de la erupción del 1 de octubre de 2021 (Copernicus)

Land reclaimed from the sea

The current eruption and those during the last 500 years have caused the island to extend westward, leaving lava platforms on the seabed.

Todoque

2021

Cumbre Vieja.

So far, the eruption

has created more

than 30 hectares

of land on the sea.

1949

San Juan

Puerto Naos

Some of the most-productive banana plantations on the island are located on land reclaimed from the sea by the eruption of the San Juan volcano in 1949.

1585

Tahuya

Updated with data from the eruption as at October 1, 2021 (Copernicus)

One of the main questions about the La Palma eruption is where exactly the magma emerging from the mouth of the volcano comes from. Another question is whether it gushes out instantaneously or if it’s a gradual process that takes millions of years. Volcanologists think that under the Canary Islands there is a “hotspot,” a reservoir of extremely hot magma that continually seeks a way to emerge, producing earthquakes and buckling the surface of the islands until they crack. These cracks allow the magma to push through the crust to form volcanoes. This is the same type of volcanic activity that created the Hawaiian archipelago in the US. However, the hotspot theory is controversial because it does not fully explain all the activity in the Canary Islands; for example, the eruptions on old islands such as Lanzarote in relatively recent times.

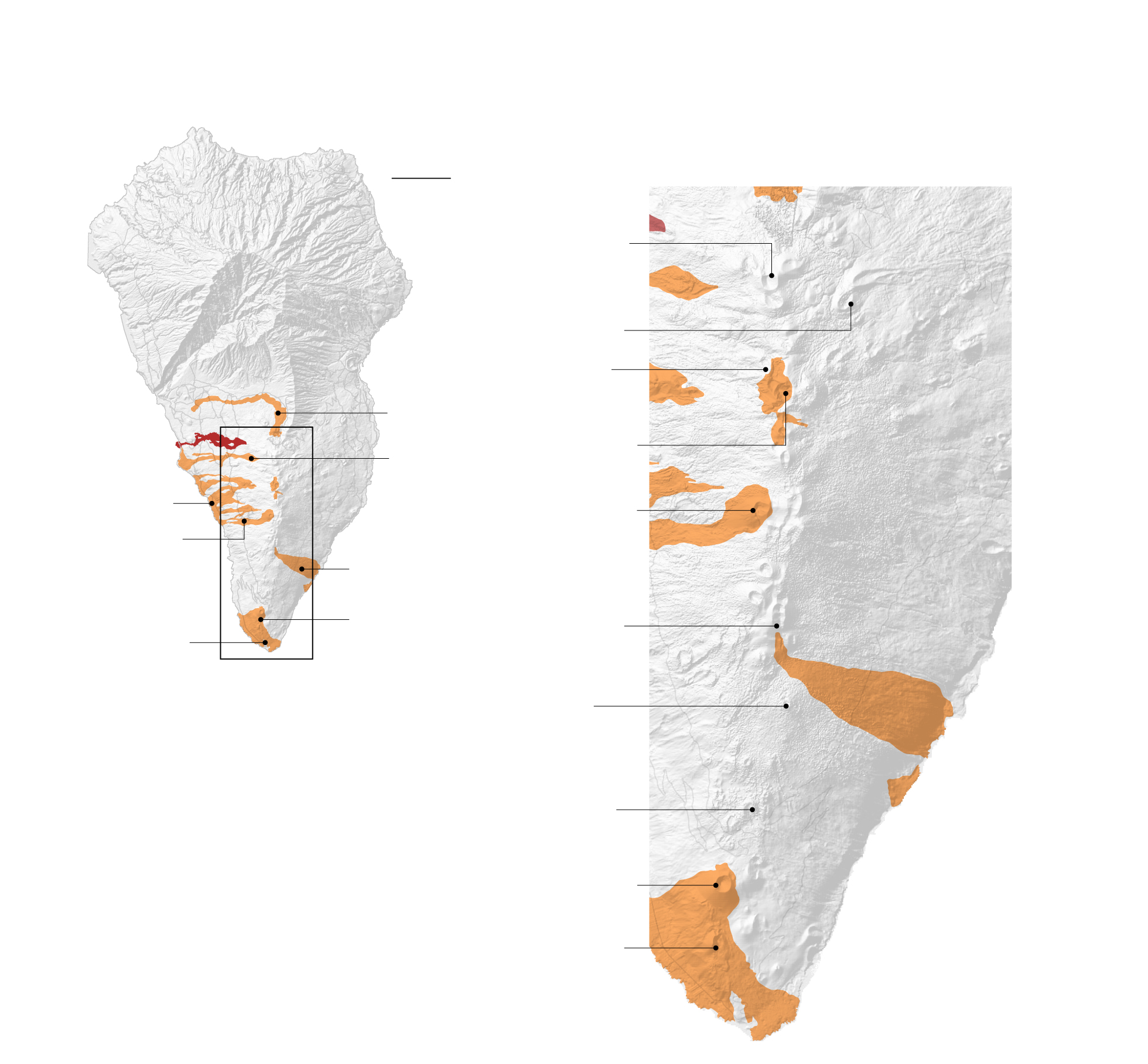

“In the hotspot, the [temperature of the] magma is about 200º C higher, which makes it more buoyant,” explains Carracedo. “It’s the same as when you push a ball to the bottom of a pool and it shoots to the surface. This is the process that has created all the Canary Islands and is still going on. New islands will certainly emerge, always to the west, but we will not see any of them, because it will happen in millions of years.” In the same way, the oldest islands, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, are gradually disappearing through a process of erosion and will end up under the sea.

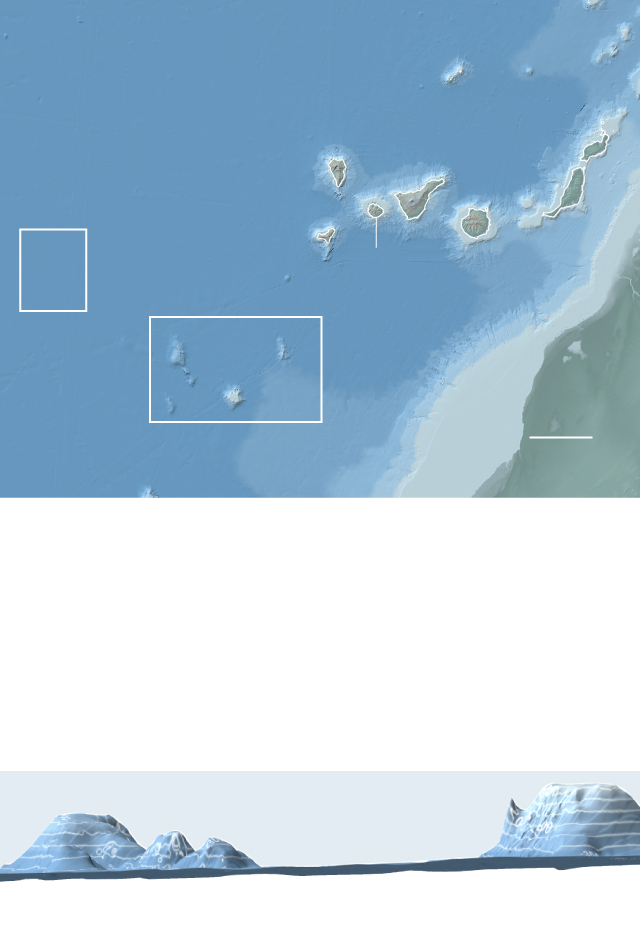

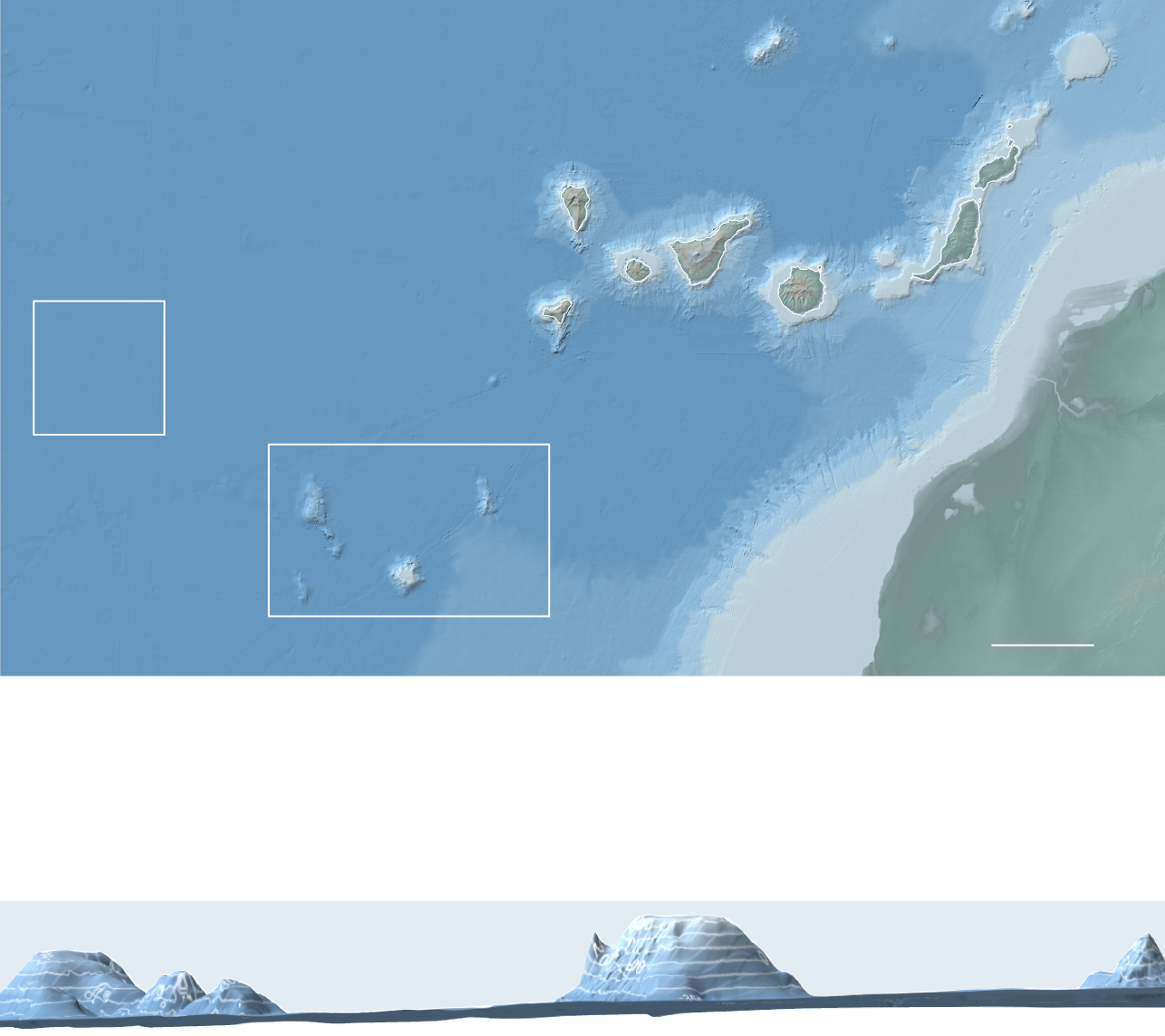

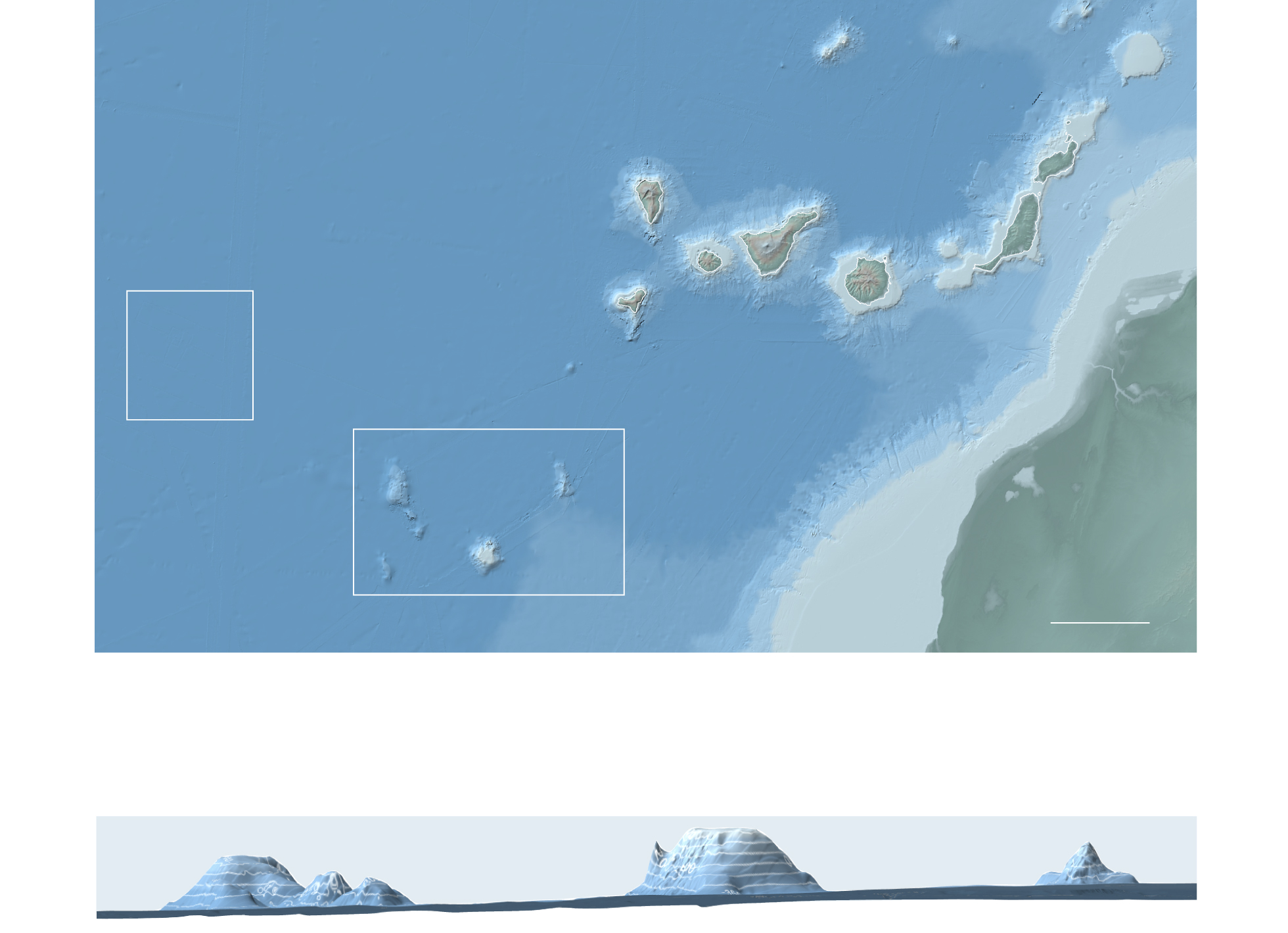

Canary Islands

Lanzarote

Atlantic Ocean

Tenerife

La Palma

Fuert.

The sons

El Hierro

Gran Canaria

La Gomera

AFRICA

100 km

The grandmothers

The seabed of the Canary Islands is a string of submerged islands that were once above sea level. They are extinct volcanoes that are known to some scientists as Las abuelas, or “ the grandmothers.”

0

The grandmothers

-3,500

Canary Islands

Lanzarote

Atlantic Ocean

Tenerife

La Palma

Fuert.

The sons

El Hierro

Gran Canaria

La Gomera

AFRICA

100 km

The grandmothers

The seabed of the Canary Islands is a string of submerged islands that were once above sea level. They are extinct volcanoes that are known to some scientists as Las abuelas, or “ the grandmothers.”

0

The grandmothers

-3,500

Atlantic Ocean

Canary Islands

Lanzarote

Tenerife

La Palma

Fuerteventura

La Gomera

The sons

-5,000 m

Gran Canaria

El Hierro

-4,000 m

The grandmothers

AFRICA

-4,000 m

-500 m

-1,000 m

100 km

-2,000 m

-3,000 m

The seabed of the Canary Islands is a string of submerged islands that were once above sea level. They are extinct volcanoes that are known to some scientists as Las abuelas, or “ the grandmothers.”

0

The grandmothers

-3,500

Atlantic Ocean

Canary Islands

Lanzarote

Tenerife

La Palma

Fuerteventura

La Gomera

The sons

-5,000 m

Gran Canaria

El Hierro

-4,000 m

AFRICA

The grandmothers

-4,000 m

-500 m

-1,000 m

100 km

-2,000 m

-3,000 m

The seabed of the Canary Islands is a string of submerged islands that were once above sea level. They are extinct volcanoes that are known to some scientists as Las abuelas, or “ the grandmothers.”

0

The grandmothers

-3,500

The map above shows where new Canary Islands may currently be in the process of being born. In 2017, a research vessel located an area 400 kilometers west of the island of El Hierro where they discovered new submarine volcanoes that have recently been active or may even be active now. They lie at a depth of about 5,000 meters. It makes perfect sense that they are to the west as it matches the movement of the Earth’s crust over the hotspot. “We believe that these are the embryos of the new Canary Islands,” explains Luis Somoza, a marine geologist with the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME) and a member of the 2017 expedition.

To the south of the aforementioned area, there are other extinct submerged volcanoes that some scientists call “las abuelas” or the grandmothers of the Canary Islands. They appeared about 120 million years ago due to the activity of another hotspot, emerging from the sea only to sink back again about 70 million years ago at around the time the dinosaurs were becoming extinct.

Many of these submerged islands were discovered only a few years ago by Somoza’s team. The shape of some of them is almost identical to the Canary Islands that are visible today, as if they were a sort of experiment; “a pre-Canary Islands,” as Somoza puts it.

Somoza has led several expeditions to study these submarine mountains – or seamounts as they are known – both those already identified and other new ones that have been baptized by his team: Drago, Bimbache, Ico, Pelicar, Malpaso, Tortuga and Las Abuelas.

The volcanoes of the Canary Islands are fundamental to Spain’s expansion of its maritime borders. The research carried out by Somoza’s team lends weight to an official petition to the United Nations arguing that some of the submerged islands form part of the Canary Islands and that, therefore, the exclusive economic zone that grants Spain special rights over those waters should be expanded. If the proposal is approved, a marine territory equivalent to half of mainland Spain could be gained, according to those responsible for the initiative.

“If part of the island collapses and falls into the sea, it becomes a natural extension of the land that is above the surface, so it would be within Spanish borders,” says Somoza. This is also the case with the debris that has formed a carpet over the seabed near El Hierro and could increase the exclusive economic zone by a radius of 60 miles. Somoza explains that “another way to grow is for a new island to emerge, as almost happened in 2011 after El Hierro’s underwater volcanic eruption. It was only 80 meters from the surface. If it had emerged, this would have been the new territorial boundary of El Hierro.” Somoza also notes that if the lava delta – where the lava meets the sea – created by the Cabeza de Vaca volcano continues to grow and surpasses those created by past eruptions, Spain’s borders will expand.

Luis Sevillano and Jacob Vicente López contributed to this story.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Sources: Roberto Rodríguez, editor of the geological guides to the National Parks of the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain, Copernicus satellite system, La Palma’s Cabildo Insular, the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain, Bing Maps, “Canaries: Intraplate Volcanic Islands” (Geo-Guías) and Science Direct (“The geology of La Palma”).