Studies shed new light on origins of Canary Islands population

DNA-based evidence and archeological research confirm ties to Berbers from North Africa, not to Celts as once believed

Scholars admit that the history of the Canary Islands before it was conquered in the 15th century by Europeans still represents one of Spanish archaeology’s greatest mysteries.

The scientific community is divided over the issue; in fact, they can’t even agree on when the first wave of people arrived here. But archaeologists, historians and geneticists have taken significant steps in their quest to discover the origins of the modern residents of the Spanish archipelago.

There’s still a long way to go, but we are closer to finding an answer to the question of where we come from

José Farrujia de la Rosa, archeologist

Studies by Rosa Fregel, a geneticist at the department of Biochemistry, Microbiology, Cell Biology and Genetics at La Laguna University, show that, depending on the island, a large portion of the population still carries mitochondrial DNA (inherited from one’s mother) from the original population.

José Farrujia de la Rosa, an archaeologist who teaches at the same university and is the author of a recent book called Identidad canaria (or, Canarian identity), also sheds new light on the main secrets of a civilization whose material presence has all but disappeared, though not its impact. Farrujia de la Rosa recalls that the original inhabitants had two different writing scripts, that they arrived in two separate waves from North Africa, and that they lacked horses or oxen as their vessels were too small to carry these heavy animals.

It all began with a type of lichen known as orchilla, which was used to make a purple dye that was in high demand for clothing. In the early 15th century, a Norman nobleman named Jean de Béthencourt secured support from Henry III of Castile to go conquer those faraway islands, whose presence had been documented at least since the times of Roman historian Titus Livius. There were brutal cultural and military clashes between the indigenous population and the Castilians, and it took nearly 100 years of fighting to take possession of all seven islands.

And so indigenous culture sank into the mists of history. Between the 16th and 20th centuries, several theories emerged as to the origins of the Canary people. Some of them claimed a Celtic ancestry, while others asserted their origins were Indo-European.

But archeological and DNA-based research has proven that the first inhabitants of the Canary Islands were Berbers (also known as Amazigh), a people who extended throughout North Africa more than 3,000 years ago, occupying what is today the area from Libya to the Sahara.

In an article published on the website of La Laguna University, Fregel explains that it is possible to determine that the global population of the Canaries has an aboriginal matrilineal lineage of 55.9%, while the European and Sub-Saharan African components are 39.8% and 4.3%, respectively.

But the results vary considerably taking each island separately. The highest rate of indigenous origins are on La Gomera (55.5%) and La Palma (41.0%), whereas the lowest values are on Tenerife (22.0%) and El Hierro (0.0%).

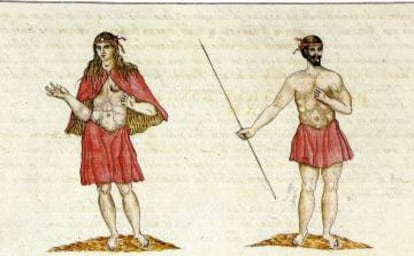

In her article, Fregel adds that “thanks to DNA analysis, we’ve been able to dispel the notion that Guanches [the name given to the original inhabitants of the islands] were practically Vikings: tall, blond and blue-eyed. Everything indicates that they came from North Africa and were physically similar to the Berbers: white skin with a tendency to an olive complexion, and brown eyes that could be light-colored in some cases. Clichés and legends notwithstanding, the ancient inhabitants of the Canary Islands were not so different from today’s.”

Sea voyage

But how and why did these early voyagers arrive in the archipelago? Farrujia de la Rosa talks about two major migration waves, the first around 2,500 years ago (radiocarbon dating was not conclusive) and a second one around the first century AD, coinciding with the Roman presence in the north of Africa.

They are believed to have made the crossing in small vessels – no remains have been found – and disembarked in the easternmost islands: Lanzarote and Fuerteventura. Nobody knows how many individuals managed the journey, but scientific calculations suggest that 14 couples would have been enough to populate the islands. The second wave took place during Roman times, when a Latin-Canarian writing system was introduced in Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, among other cultural elements. Before that, inhabitants had used the Libyco-Berber script.

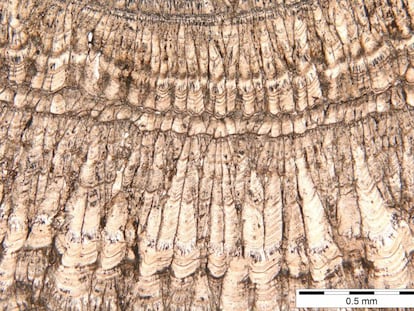

The Canary Islands lack iron mines or any other significant source of metal, so the early inhabitants were forced to adapt their knowledge of metallurgy to the local environment. This gave rise to the use of obsidian and basalt for toolmaking, and to a kind of ceramic decorated in ocher tones not unlike that seen in North Africa.

“They worshiped the sun and the moon, but also the mountains, the roques (large rock formations) and the caves, just like the Amazigh,” explains Farrujia de la Rosa. “The research has borne fruit after decades of controversial theories. There’s still a long way to go, but we are closer to finding an answer to the question of where we come from.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.