Explaining the world to an alien

A disk with images and sounds from our planet was sent out on the two ‘Voyager’ probes, as well as a recording of a person’s thoughts, in case aliens can read brain waves

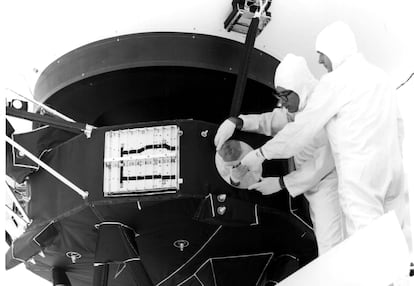

The farthest human artifacts from our planet are the two Voyager probes, launched in 1977. In addition to transmitting data, they served a second purpose: traveling to infinity in case someone, someday, came across them. That’s why the probes carry an hour-and-a-half-long Golden Record, resembling an old vinyl LP, containing greetings in 55 languages, sounds, and images. There’s Bach, Chuck Berry and tribal chants. Crickets chirping, a ship’s siren and laughter. Today I think it would be inevitable to add a video of a cat. My favorite greeting is in the Chinese Amoy dialect: “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” In 2012 and 2018, respectively, the probes passed the boundary of our Solar System, and as you read this they are still heading into the unknown. The last I heard, a minor news item among the decisive controversies of the day or the explosive statements of a soccer coach, was in August: communication with Voyager 2 was recovered after being lost for a few days.

Now we are once again interested in UFOs, or UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena): NASA has just presented a study, while Mexico has announced the discovery of some mummies that look like cousins of E.T. The more our anguish about the world’s problems grows, the more we want to distract ourselves with something that is beyond our knowledge and, if possible, our responsibility. Like the fad of superhero movies, people who are genuinely capable of solving problems.

If an extraterrestrial were to arrive here, besides being interested in our knowledge of quantum physics, the footprint of the Roman Empire and, as a result of blanket press coverage, what Kim Kardashian is up to this week, he would probably ask if it is possible to meet Ann Druyan (it is, she is still producing books and programs). Druyan, a member of Carl Sagan’s team (they later married) participated in the Voyager records and was the one who came up with the idea of adding something extra. As other beings perhaps had the ability to read brain waves, she proposed including a recording of someone’s thoughts as well.

She was selected for the task and what she was thinking was recorded for an hour. Druyan prepared for it, of course, and during the session she mentally reviewed the history and the greatest ideas of mankind, as best she knew how. What a moment: consider the responsibility of not coming up with a load of bullshit or thinking about the grocery list. I doubt, moreover, that a Western citizen today could go an hour without looking at their cellphone to concentrate only on their own reflections. Druyan also thought, for the record, of the wars, violence, and disasters caused by human beings, and concluded with this: “Toward the end I permitted myself a personal statement of what it was like to fall in love.”

I always imagine an alien arriving, holding a press conference or whatever, and saying that he thinks he has understood the famous records, but that the final part needs to be explained to him because it is the most mysterious thing of all. In weeks like this, where we feel beset by tragedies — in Morocco, in Libya, in Ukraine — and human stupidity seems more powerful than ever, we really have to hold on to that small part of us, to the most beautiful, elevated, decent and mysterious thing we have in order not to fall into despair, as well as to relativize some of the problems facing this blue dot suspended in the dark, where on the bright side the food isn’t bad.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.