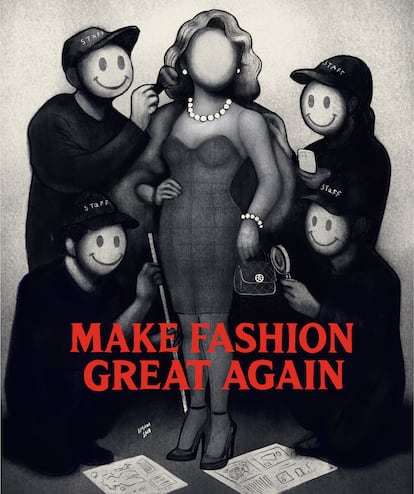

From quiet luxury to prairie dresses: How fashion became ultra-conservative

Runways, influencers, and fast fashion are embracing an image that discreetly evokes a reactionary feminine ideal — and the look is proving seductive to younger generations

“Quiet luxury hinted at fatigue of the loud, anything-goes culture of the previous decade. Many women were simply tired of being told ‘sex sells’ or that empowerment means ever-shrinking hemlines. Quality over quantity, tradition, subtlety — these were back in vogue.”

The passage could have appeared in an old book about the perfect woman, but it actually comes from an April article titled How Fashion Predicted A Trump Triumph in the magazine Evie, a fashion and lifestyle publication that embraces and espouses conservative values. The influence of Evie in the United States has led even The New York Times to dedicate an extensive profile to its founder, Brittany Martinez.

The magazine is not the only one to have explored the links between fashion and reactionary shifts. A quick search on the subject pulls up dozens of articles in publications that are hardly MAGA. “If anyone says I didn’t know our country was going down a conservative path, I would ask you, have you been on the internet in the past four years at all?” joked TikToker Lindsey Louise in a viral video posted after the last presidential election.

@officialnancydrew looking at trends, it has be obvious our climate was moving conservative for years, i wrote about this on my substack and i honestly could talk about this forever lol. from everything wellness to trad wife content to old money aesthetic to the constant need to be “edgy” we have seen the shift in culture online. also i note that some of these concepts have been taken from indigenous cultures and were constructed into ytness and “ luxury “ rebrand. ffashiontrendsffashiontiktokssocialmediap#politics

♬ original sound - lindsey louise

Fashion is not just about clothes, as sociologist Diana Crane points out in her 2000 book Fashion and its Social Agenda. Rather, she says, it is a reflection of our norms and cultural values. As such, it has the potential to influence social attitudes towards body image and beauty standards.

The idea is perfectly applicable a quarter-century after her book’s publication. In recent years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, a series of aesthetics inspired either by nostalgia or by the archetype of the billionaires have taken hold. From floral dresses meant to evoke a bucolic shepherdess, to beige suits that could be worn by Siobhan Roy in Succession, or the flawless (and highly desirable, like a donut) face with a slicked-back bun of Hailey Bieber and her followers.

At first glance, these elements might seem unrelated, if not for the fact that a deeper reading of these macro-trends reveals a kind of pursuit of perfectionism and discretion that fits like a glove with more conservative values.

“If we want to understand current trends, we can observe what is happening in the world in political terms,” reflects Daphné B., cultural journalist and author of Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture Under Late Capitalism. “There has been an obvious rise of the ultra-right, in Europe as well as the United States. In consequence, the values and aesthetic of conservative movements are appreciated, because they are those closest to power.”

Tags like #coquette, #cleangirl and #oldmoney now belong to the general slang of young people; so do words like Ozempic, tradwife and the lamentable “classic chic.”

“There are influencers who call themselves ‘stay at home girlfriend’ or ‘stay at home mum,’” explains Carla Vázquez Jones, a fashion communications consultant in New York who has worked for brands like Loewe and Etro. “Fitness divas who go for their iced matcha and pilates class, but don’t work. Within this perfection, you also find the clean girl which, as I interpret her, is a style. It looks like you’re not wearing makeup, but you obviously are, just with a dewy finish.”

She continues: “There’s also the 1990s look embodied by Carolyn Bessette, patron saint of minimalism. She wore pencil skirts, tall boots, visible bras, headbands. Then in the third ring of perfectionism you have trad wife style, with dresses that look like they came out of 1800. Very Southern, with pastel colors, a little 1950s. The concept is fraught: it comes with the idea that you should be home, taking care of your children, cooking for your husband.”

More and more young people are looking to emulate that image, and of course, there are many influencers who are happy to model such a lifestyle.

As Crane puts it, fashion reflects the societal values of the moment, and runways have been quick to channel these trends that appeal to an ideal of conservative femininity. In the fall-winter shows, countless tailored dresses, knee-length skirts, synthetic fur coats that scream economic opulence, and the return of high heels have been seen.

It bears mentioning that more than 80% of creative directors in the major fashion houses are men, the most unequal ratio in 50 years. Also, that sophistication, decorum and refinement are terms that have returned to the pages of fashion magazines, defining feminine ideals that we once seemed to have left behind.

The phenomenon is already reflected in shopping trends: in the last month, compared to the same period in 2024, online searches for equestrian boots rose 39%, and knee-length skirts 33%; prints such as large polka dots increased 49%, and gingham checks — a popular pattern in the 1950s, when this conservative female ideal also prevailed — 33%.

Those statistics were released by fashion technology company Heuritech, whose fashion director Frida Tordhag offers this analysis: “We are witnessing a more conservative era in fashion, on an aesthetic as well as cultural. After years that were dominated by the urban aesthetic and inspired by the 2000s, full of daring silhouettes, low-cut tops and vanguard styles, we are seeing a shift to something more refined and evergreen. Even the fast fashion brands, which cemented their success through micro-trends and party clothes, are reinventing themselves and adopting cleaner lines, discreet silhouettes and a more sophisticated aesthetic that can be described as conservative.”

A canon of hegemonic beauty is becoming more widespread in certain circles: svelte but toned bodies, tanned skin and blonde manes (note, this is an ideal that only works for white people).

“There is a plethora of reasons that drive us to modify our bodies,” says Daphné B., “and one of them is the social advantage enjoyed by those who adjust to the prevailing ideal. Because again, those who set certain standards are those who hold the power.”

She continues: “U.S. poet Claudia Rankine studied the pursuit of blondness and its prevalence in politics. To her, it is connected to whiteness, desirability and privilege. Experimenting with the body is a matter of freedom, yes, but she uses the term ‘complicit freedom’ to indicate that what we like is what’s most valued. Beauty culture is optional, but if you choose not to participate, there are consequences.”

This is no abstract theory. “I have a group of American friends and all of them, without exception, got Botox done before they turned 30,” says Vázquez.

Connecting the dots

This aesthetic shift, which leans on hyper-feminization, hadn’t been experienced so visibly since the mid-20th century — “perhaps the archetypal moment in exemplifying a restrictive fashion that responds to a conservative shift,” notes Juan Gutiérrez, head of the contemporary clothing collection at Madrid’s Museo del Traje.

He continues: “That was when the brakes were applied to the social advancements made during the 1920s and 1930s. Specifically, the process of female emancipation was cut short by a situation in which it was thought that alleviating the trauma of war required a return to traditional structures, with female figures fulfilling their domestic duties while beautifying themselves to satisfy male erotic fantasies. This was the era of bullet or torpedo bras, which gave the bust a conical shape that was projected in a hyperbolic manner, the effect being accentuated by garments that narrow the waist. The restrictive nature of such trends dominated until youth fashions took over.”

Since the 1960s, it has been young people opposing the system who drove fashion’s evolution, turning it into a tool for self-expression. Now, the tables have turned.

Today, the confusion of adolescence is compounded by the perfection sold on social media, which is young people’s channel for interaction with the world around them. “The generation that is now 20 has grown up with the belief that there is no future,” explains journalist Elsa Cabria, who recently launched a podcast about how the ultra-right global network has put women’s bodies at the epicenter of a cultural and political battle.

“If as a young girl, you don’t see anything else, you consider becoming a trad wife to be a possibility, because you think that you won’t get anywhere by working. The risk is that you buy into the whole package,” says Cabria. “Perhaps we are asking young people to think, analyze, reflect, for them to draw conclusions and be more intelligent than a very perverse system. At the height of feminisms, there were many women, but not all — some felt excluded. They thought we had gone too far. Now, they see themselves represented in this other kind of woman and that you should too, because it has cost too much to get to where we are.”

Cabria thinks the response must be to rebel, to go against, “though in reality, they’re letting themselves be manipulated by the ultra-conservative majority, they think it’s trendy.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.